Pyramidology

What is pyramidology?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines pyramidology as “the study of or theory about mathematical or occult significance in measurements of the Great Pyramid of Egypt.” While the field began with genuine curiosity about the pyramid’s structure and dimensions, it has since evolved into a broad and often speculative area of thought. My project explores how pyramidology has transformed over time, from early empirical studies to symbolic and pseudoscientific theories. It will begin with one of the earliest mentions of the Pyramids in literature by Herodotus, and end in the 21st century by looking at theories descibed by guest on The Joe Rogan Experience.

Earliest Mentions- Herodotus

Herodotus, often called the “Father of History,” was a 5th-century BCE Greek historian known for writing The Histories, one of the earliest attempts to record the events and cultures of the ancient world.

While the main focus of the work is the Greco-Persian Wars, Herodotus includes detailed accounts of his travels through Egypt, Persia, and other regions. In his descriptions of Egypt, he shows an interest with the pyramids, offering some of the earliest written accounts of their construction and dimensions.

Regarding the pyramid itself, Herodotus makes some general physical descriptions of it, along with a rough estimate of its dimensions, believing it to be 800 feet tall and 800 feet wide. He then attempts to explain how it was constructed, suggesting that a wooden machine may have been used to lift the blocks. However, the majority of his writing focuses on the slave labor required to build the pyramids, leading him to view them as monuments of cruelty and blood rather than architectural wonders.

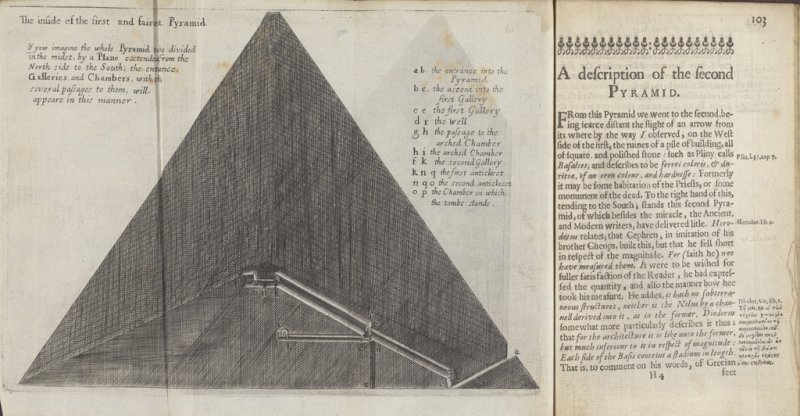

The true “study” of pyramids, also known as “pyramidology,” began in the 17th century with John Greaves, an English mathematician who traveled to Egypt to take measurements of these wonders of architecture.

Previous works regarding the pyramids, such as those of Herodotus, consist mostly of simple visual observations and rely heavily on storytelling and hearsay, particularly from a local priest. Greaves, on the other hand, took an empirical approach, recording various measurements such as the lengths of individual blocks, the angles at which the pyramids rise, and larger calculations including base length and height. He also offers multiple critiques of earlier works, including The Histories. In response to Herodotus’ estimate of the pyramid’s base as 800 feet, Greaves measured it by hand and calculated it to be 693 feet, which is significantly less than the priest-reported figure Herodotus cited. Another major departure in Greaves’s work from previous approaches is his use of mathematical reasoning. When calculating the height of the pyramid, he imagined the structure as four equilateral triangles sitting on a square base, allowing him to apply what we now know as trigonometry. While these methods may seem basic by today’s standards, Greaves’s work, primarily made up of precise measurements, marked a major step forward in how people studied the pyramids, transforming the subject into an early form of pyramidology.

A Shift Toward pseudoscience

While Greaves’ influential work helped establish a true “study” of the pyramids helping encourage people to examine them in a scientific manner. This approach would evolve further in the 19th century, increasingly trending toward pseudoscience. One influential example is John Taylor’s The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? And Who Built It?, in which Taylor offers a new perspective on the pyramid, suggesting it was more than just a tomb.

2One theme seen in Taylor’s work is the belief that the pyramids served as more than just tombs; rather, he argued they were repositories of mathematical knowledge. He suggested that the builders knew the Earth was a sphere and had calculated its circumference, leading them to design the pyramids in a way that symbolically represented it. Taylor claimed that the Great Pyramid’s perimeter is 1/270,000 of the Earth’s circumference. In addition, he believed the pyramid’s height corresponded to the radius of a circle whose circumference equaled the base perimeter. This, he argued, mirrored the relationship between the Earth’s radius and its total circumference. To Taylor, this precise ratio was evidence that the pyramid encoded advanced knowledge of the Earth’s size. He believed these connections were not coincidental and argued that the pyramids were not built by ancient Egyptians. Instead, he claimed they were built by Christians, possibly descendants of Noah who had received this knowledge from God.

Where do these ideas stem from?

John Taylor’s theories about the Great Pyramid emerged during a time when science, religion, and reason were deeply entangled, particularly in the wake of the Enlightenment. Enlightenment thinkers emphasized that the universe operated according to rational and mathematical laws, and many believed that uncovering those laws was a way to better understand the mind of God.

21st century pseudoscience

The 21st century saw a broad trend of pseudoscience, from astrology and flat Earth, to ancient aliens building the pyramids. With all of these different ideas, there seems to be a common theme of appointing a simple theory to a concept that is complex, such as not being able to see the curvature of the Earth from land.

This also lines up with the pyramid as it can be hard to understand how such a massive and precise structure was built many years ago with seemingly primitive tools. Rather than accept the complex and labor-intensive realities of ancient engineering, logistics, and social organization, some people turn to fantastical explanations.

The image above is from an article written by Abdul-Wahab El-Kadi, published in Scientific Research: An Academic Publisher, where he describes his theories regarding abolishing gravity in order to build the pyramids. The problem El-Kadi has with the typical historical narrative, regarding how the pyramids were built by people dragging the large blocks across the desert and then up ramps is, as he writes, “impractical.” Because of this impracticality, El-Kadi argues that they must have had some kind of advanced technology. He offers two different theories: acoustic levitation and hydro lifting.

Acustic lift

hydro lift

This idea stems from the theory that solid matter can be suspended on top of a sound wave. He explains that the Egyptians could have produced a sound that would allow them to lift the large blocks without exerting physical force. Part of his “evidence” is the large room in the pyramid, with walls lined with dolomite and granite, both, he notes, could have been used to direct sound waves through the structure. Additionally, he references a network of underground passages within the pyramid that, in his view, could have been used to direct and control these sound waves. The Void and the underground passages are what he calls “physical evidence,” which is the extent of the “proof” he offers in the theory.

El-Kadi offers another theory called hydro lifting, which is based on the idea that the ancient Egyptians could have used water pressure to help lift the massive stone blocks. He points to the Nawamis, which are small circular stone structures that predate the pyramids, and speculates they were used like ancient water chambers. According to his theory, filling two connected chambers with water, one smaller and one larger would allow pressure from the smaller one to push up with greater force in the larger, lifting heavy blocks vertically. The evidence for this theory, being the Nawamis, is not rooted in fact, as there is no record of these structures being filled with water, nor has this method been replicated today.

El-Kadi’s theories are just one of thousands easily found through a simple Google search showing ideas that present themselves as scientific but, in reality, lack credible evidence and cannot be proven or tested. These kinds of speculative narratives have become increasingly popular in today’s age, where information spreads quickly and sensational theories often overshadow well-supported historical research. Nowhere is this more apparent than on platforms like The Joe Rogan Experience, one of the most-watched podcasts in the world.

episode 1897

The clip above is taken from Episode 1897 of The Joe Rogan Experience, which is available in full on YouTube and Spotify. This segment offers a clear example of how Rogan’s guests, Graham Hancock and Randall Carlson, approach the topic of the pyramids—blending speculation and alternative history to challenge mainstream archaeological views. Hancock focuses primarily on the granite blocks in the King’s Chamber, questioning how blocks of this size could be moved many miles across the desert and placed with such precision. Hancock rejects the standard theory regarding the transportation of these blocks: that they were slid across wet sand and then set into place by hand. He takes issue not with sliding the blocks across the sand, but with the idea that they could have been brought up to the height of the King’s Chamber using conventional methods. He simply dismisses these more plausible theories, saying, “I don’t know how they did it, all I know is they did, and I don’t think anyone knows how they did.”

Instead of providing an alternative and evidence-based theory, he suggests that the only way they could have done this is if they had access to advanced technology. Due to the need for such technology in his eyes, he argues that the ancient Egyptians were part of an advanced civilization that was wiped out by an unaccounted-for apocalypse around 12,800 years ago. Accepting this theory means believing that an ancient civilization existed with technology more advanced than ours today that are capable of things modern science can’t explain. But despite this level of advancement, the believed civilization left behind no tools, infrastructure, writings, or traceable artifacts other than the pyramids. It is hard to justify that a society this advanced would leave behind no trace of itself, neither physically nor through historical records. These ideas reflect a broader trend in pseudoscientific pyramidology, where doubt and speculation often stand in for actual analysis and historical context.

Episode 2142

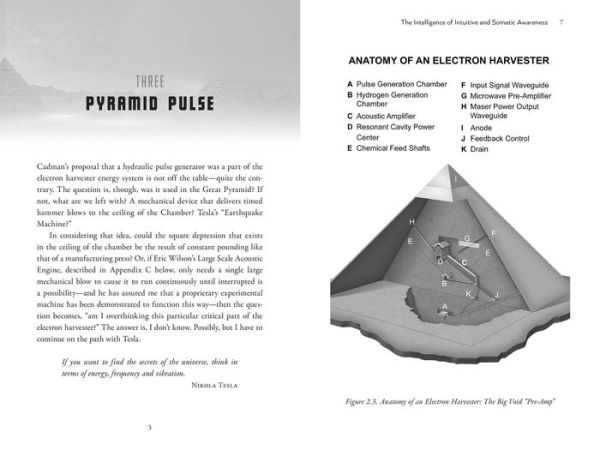

Similar to the previous episode discussed, Joe Rogan has Christopher Dunn on the show, who has a background in engineering but developed a strong interest in the pyramids, leading him to write multiple books on the topic. The historically agreed-upon theory is that the pyramids were built as large tombs; however, Dunn challenges this idea and speculates that they served as a power plant. The clip above comes from the podcast, which can be listened to in full on YouTube or Spotify. In this segment, Dunn describes how different features of the pyramid lead him to believe that the pyramids harvested energy in some way. Rogan poses several questions that Dunn struggles to answer clearly. At one point, Dunn claims that the “Northern Shaft” inside the pyramid mirrors the dimensions of a waveguide, which is somehow used to direct microwave radiation. When Rogan admits he doesn’t know what a waveguide is and asks for clarification, Dunn gives a vague explanation that’s difficult to follow. He eventually explains, in a roundabout way, that a waveguide is a structure that channels microwave energy, and because the Northern Shaft has similar dimensions, he believes it may have been used to direct energy inside the pyramid.

Due to the obvious difficulty Dunn had with the interview, I thought it best to look into some of his writing, where he articulates his ideas in a much clearer way. In his book Giza: The Tesla Connection – Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean Energy, Dunn explains his theory that the pyramids were designed to harvest electrons from igneous rocks beneath the Earth. His entire theory is based on the “electric phenomena” that he says many people feel when visiting the pyramids which is something he claims cannot be described. He explains that this sensation could come from igneous rocks releasing electrons into the pyramid, which is the form of energy Dunn believes is being harvested. In order to release these electrons, Dunn says the pyramid would have produced an acoustic vibration to activate the energy. Throughout the book, Dunn points to various features of the structure that could, in some way, be used in the process of harvesting energy, such as the large room lined with granite known as the “Void,” or the long tunnel passages. All of this evidence is presented as something that could have been used for energy harvesting, but he does not provide concrete evidence that the pyramids were actually designed with this purpose in mind.

Concluding thoughts

The rise of figures like Graham Hancock, Randall Carlson and Christopher Dunn, along with the growing popularity of pyramid-related pseudoscience in the 21st century, reflects a deeper cultural trend in how we relate to the past, particularly ancient Egypt. Throughout history, ancient Egypt has often been viewed as a spectacle, especially by the Western world, and in today’s media-driven society, where entertainment often takes priority over truth, these fantastical ideas are amplified more than ever. These theories imply that ancient Egyptians weren’t capable of building the pyramids themselves, suggesting they needed help from aliens, lost civilizations, or forgotten technology. While it seems contradictory, to say that the Egyptians were a technologically advanced civilization, I believe discredits the ingenuity, organization, and skill of the real, historically accurate ancient Egyptians.

Suggested Readings

Dunn, Christopher, Giza: The Tesla Connection , Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean Energy, (Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Company, 2023).

El-Kadi, Abdul-Wahab, “The Role of Abolishing Gravity in Ancient Egyptian Pyramids Architecture,” Archaeological Discovery, Vol. 11 No. 1, January 2023. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=122713

Hancock, Graham, The Joe Rogan Experience, (Spotify, November 10, 2023), 1:13. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGJ1hyYmmTc

Herodotus, The Histories, translated: George Rawlinson, (Moscow, Idaho: Roman Roads Media, 2013).

https://files.romanroadsstatic.com/materials/herodotus.pdf

Greaves, John, Pyramidographia, (London: Printed for George Badger, 1646).

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A41967.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext

Taylor, John The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? And Who Built It?, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).