Introduction to Cook’s Egyptian Tours

Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt exposed the wider world to the treasures that lay within Egypt’s borders. The Egyptomania, or fascination with ancient Egypt, that followed this expedition encouraged Europeans and Americans to visit Egypt to witness these wonders themselves. As Egypt rose in popularity, the steam engine’s commercial use would allow passengers to travel great distances on steamships and trains, making travel to Egypt possible. Some tourists flocked to Egypt under the direction of physicians who claimed that the dry air would heal pulmonary diseases. Others sought a warm winter getaway, culminating in the construction of the Winter Palace in Luxor.

In 1882, Egypt experienced financial instability, leading to British intervention as a veiled protectorate, and, following the First World War, Egypt would become an official protectorate. While there were tourists from several nationalities, a majority of travelers in Egypt were English-speaking, and the British influence over Egypt lent to its popularity with British and American travelers. In the 1870s, alongside the rise of industrialism, workers’ rights received more focus; with the advent of the Saturday half-holiday and paid vacations, working-class members could also travel, allowing the masses to become more mobile than ever before. Tours to Egypt offered varying accommodation levels, with first, second, and third class designations for elite, middle, and working class travelers, respectively. Ultimately, Egypt would become a fashionable destination for Europeans and Americans seeking a getaway.

Why Did People Travel to Egypt?

A combination of fascination brought on by the Napoleonic excursions into Egypt and the detailed literary works that arose out of that, the innate human desire to acquire antiquities and other “collectors items” (Egyptian antiquities sold for a high price during the late nineteenth century), and increased access to travel opportunities brought on by the introduction of worker’s rights and vacation time, drew tourists to Egypt. These people from a variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic status were drawn to Egypt’s mystery and its legacy of a long-lasting yet little understood civilization.

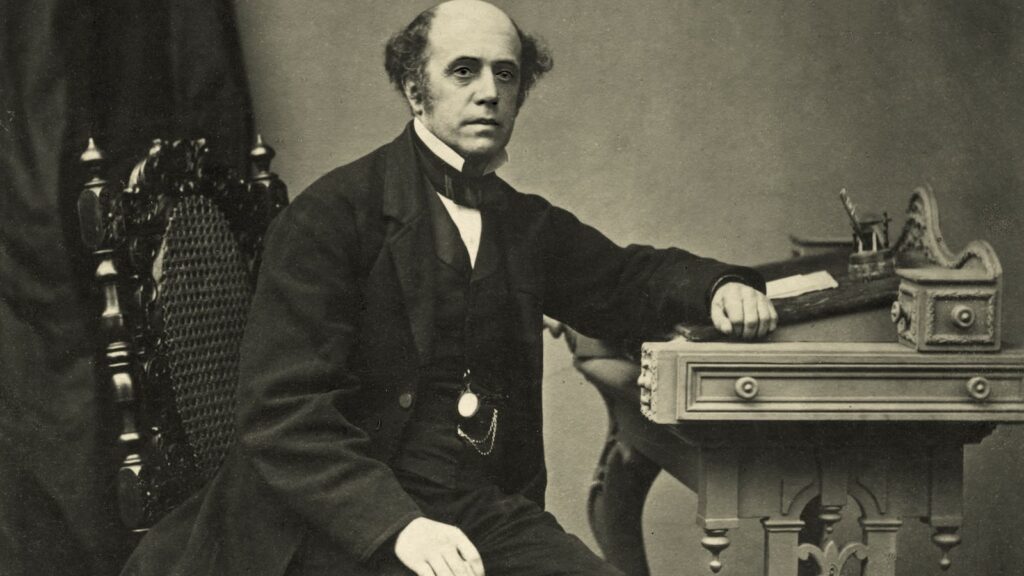

Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook, a British man who owned a printing business and had a passion for the temperance movement, set out on June 9, 1841, to convince fellow temperance activists to support his first excursion: train travel from Leicester to Loughborough, England. As he informed the temperance supporters, this excursion would allow people to engage in entertainment that did not involve alcohol consumption. Essentially, Cook’s tours began under the temperance movement, with the tours operating as a means of providing recreation without intoxication. Over 2,000 people attempted to travel on Cook’s excursion to Loughborough, though there was only room for 600, which demonstrates the success of Cook’s advertisement for the event.

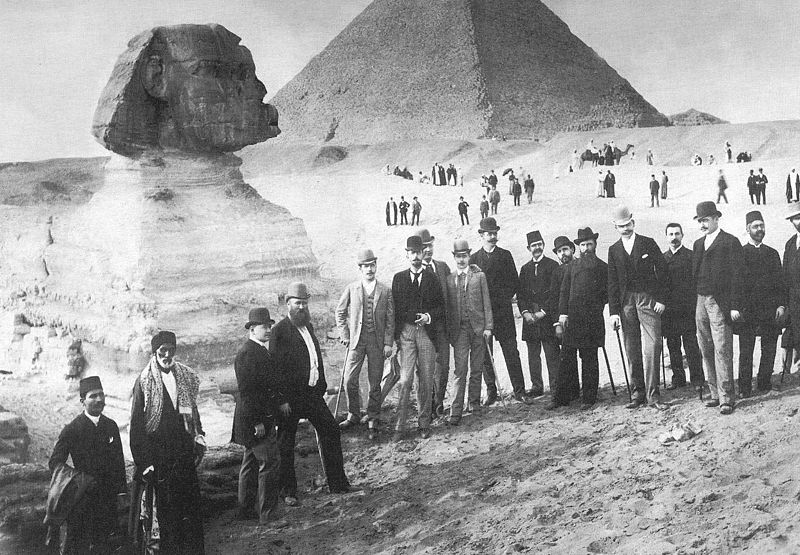

Four years later, Thomas Cook would make the fateful decision to organize tours for the masses. His first long-distance tour took a group of tourists to Scotland. In the early years of the business, profits were minimal, which led Thomas Cook to employ his son John Mason Alexander Cook, hence the business’s name: Thomas Cook & Son. After meticulous planning and preparation (from planning travel routes, to hiring guides, to attaining food and housing accommodations for his guests) Cook would eventually have successful tours in Scotland, Italy, France, and many other countries, with his Egyptian excursions beginning in 1869. By the 1870s, Egypt became a popular and desirable destination thanks to the Thomas Cook steamers, which made travel on the Nile safe yet exotic. Travelers from the Russian Czar, among many other royals, to members of the working class took tours with Thomas Cook’s travel company.

The First Egyptian Tours

Thomas Cook, a religious man, would often include the Holy Land in his tours of Egypt; however, in the late nineteenth century there were very few hotels in the region, so Thomas Cook’s tourists (led by dragomans, or tour guides), would set up camp each night of their travels. The camp could host 30 to 40 people and consisted of two dining tents, eleven sleeping tents, and one cooking tent. In 1872, Thomas Cook’s company escorted 400 travelers to Egypt and the Holy Land.

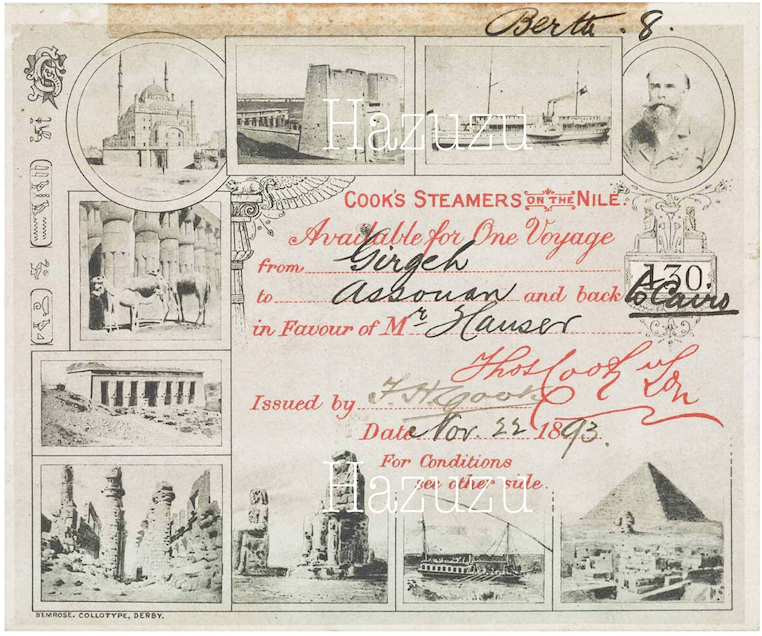

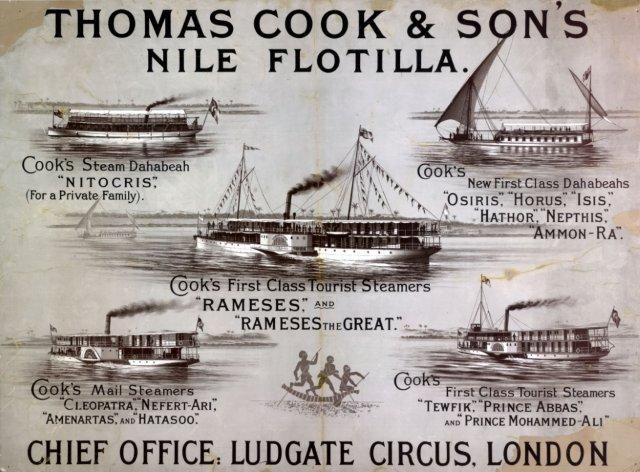

Following the initial tours of Egypt, Cook’s travelers would move to the Nile. In 1890, Thomas Cook acquired a fleet of steamers, each creatively named for famous pharaohs and gods of Egypt. John Cook also chartered steamers from the Khedive, advertising the ships as a means of “traveling under the government’s authority” with the fare for such trips ranging from £75 to£80 per person for second and first class respectively. The steamers would also carry mail up and down the Nile River to vacationers. On these ships, passengers would receive meals where the typical dinner consisted of hard-boiled eggs, cold meats, various vegetables, and a cooked pudding.

Thomas Cook’s Guide to Egyptian Travel

As his company’s popularity continued to rise, Thomas Cook published guidebooks for each of his travel destinations. An Egyptologist, E. A. Wallis Budge, wrote the Thomas Cook & Son guidebook on Egypt. The guide begins with an overview of Egyptian history that emphasizes significant artifacts and how their discovery contributed to the understanding of Egypt at that time. It provides a list of known pharaohs and the period of their rule, descriptions of the ancient and modern languages, along with a description of ancient and modern Egyptian customs.

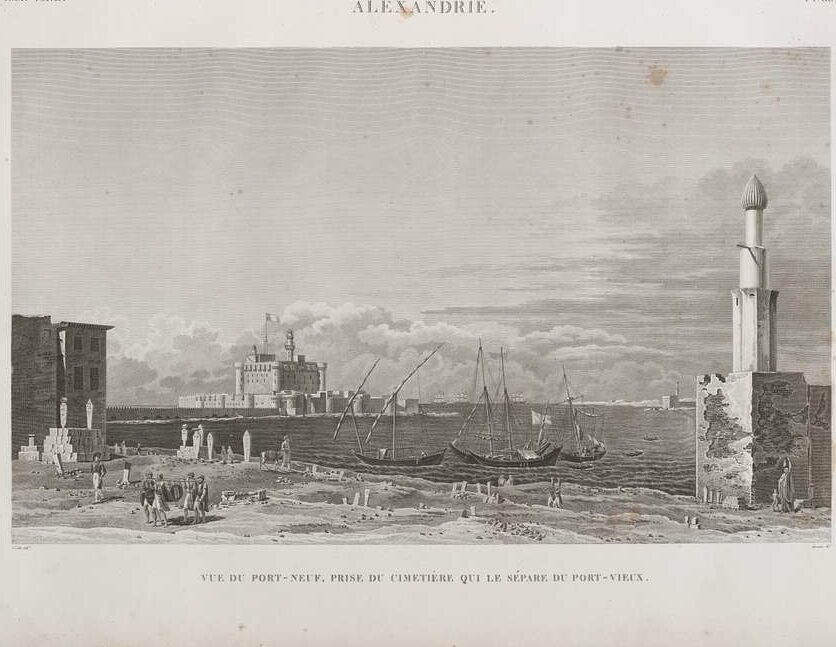

When it comes to activities available for travelers in Alexandria, Thomas Cook’s guide offers few suggestions. The guide states that the most significant sites in Alexandria were the Lighthouse, the Library of Alexandria, and the Serapeum. However, these sites have been destroyed and therefore cannot be viewed by interested tourists. Further, the city of Alexandria did not have the same level of French influence that the more popular city of Cairo did, as such, travelers were less attracted to Alexandria’s architecture and culture.

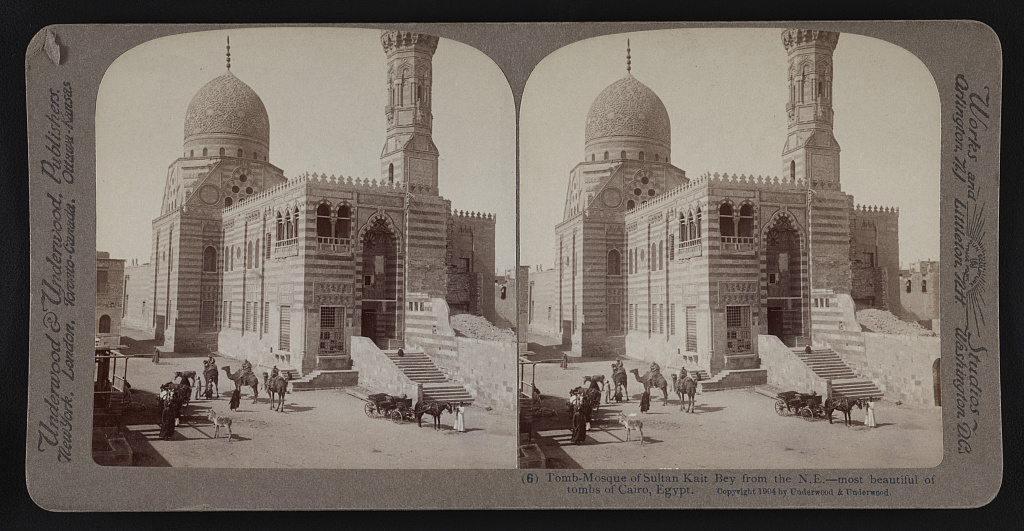

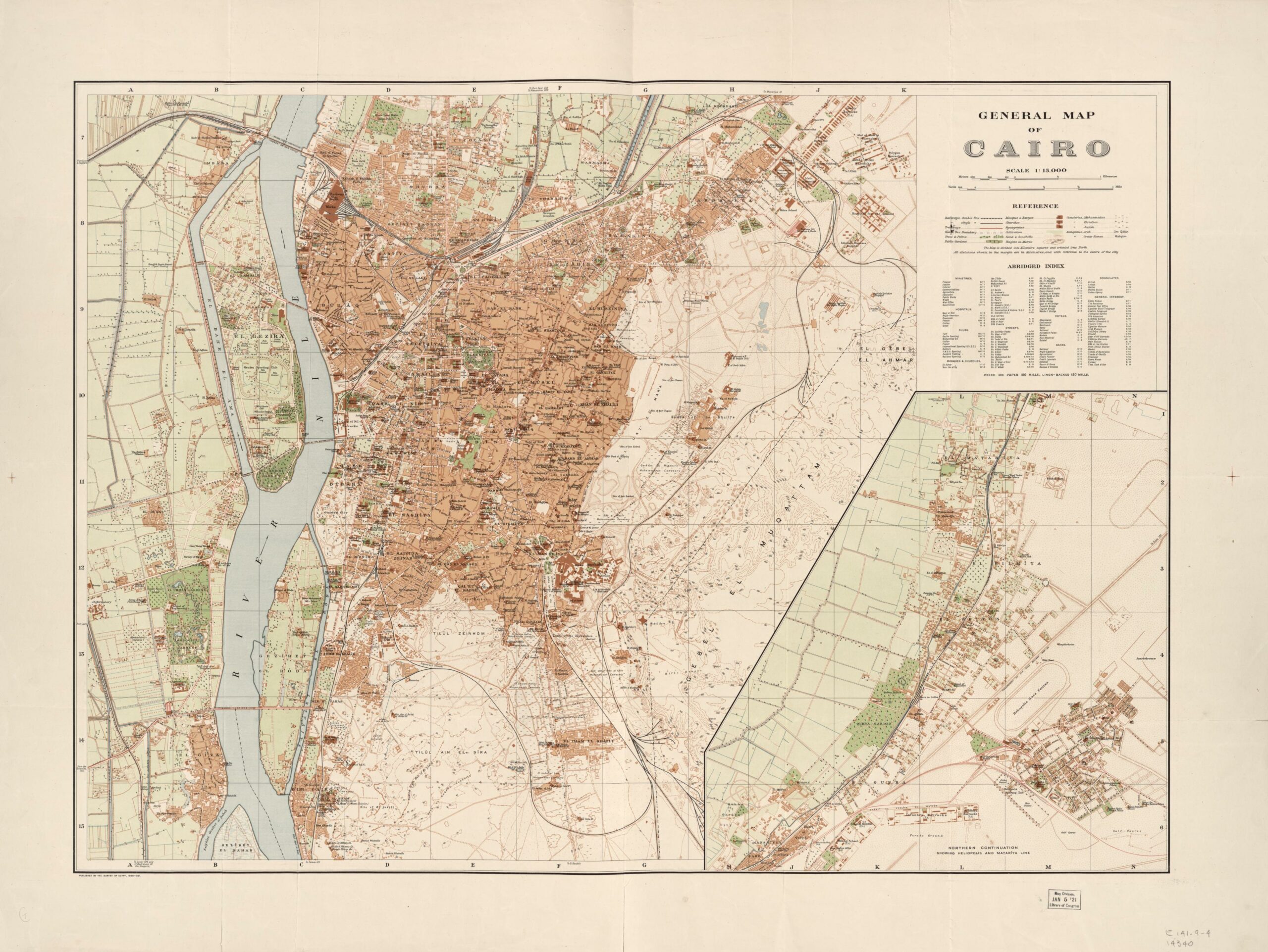

After leaving Alexandria, tourists would begin their excursion down the Nile to Cairo. Thomas Cook’s guide focuses on expploring Cairo, as the capital city of Egypt often drew the most travelers. The guide begins by recommending the museum at Giza, whose “national Egyptian collection… surpasses every other collection in the world, by reason of the number of the monuments in it which were made during the first six dynasties, and by reason of the fact that the places from which the greater number of the antiquities come are well ascertained.” The museum is described in great detail, with explanations of the contents in each of its sections provided. Next, the guide encourages tourists to visit any of the Coptic Churches, citing several choices for tourists. One example is “the Church of Mar Mina… [which] contains some interesting pictures, and a very ancient bronze candelabrum in the shape of two winged dragons, with seventeen sockets for lighted tapers.” He also informs tourists of the various mosques in Cairo, though he does not mention any elements of the mosques that might be of interest (save for “the dancing dervishes,” who perform in the “Mosque of el-Akbar.”) The tomb-mosques of the Caliphs are also suggested, as the guide states “the limestone pulpit [of the tomb of Barkuk] and the two minarets are very beautiful specimens of stone work.” Thomas Cook’s guide also states that “the most beautiful of all [the tombs of the Caliphs] is the tomb-mosque of Kait Bey (A.D. I468-1496), which is well worthy of more than one visit.” The guide devotes a chapter specifically to the Pyramids of Giza, imploring the tourists reading his guide to visit through various maps and descriptions of the structures. These sites are recommended for their historical and educational relevance, religious significance (in the case of the churches of Cairo), and overall grandeur.

After tourists saw the sights of Cairo, they would travel further up the Nile to Luxor and its ruins. Thomas Cooks’s guide recommends tourists visit Luxor, which, as aforementioned, Thomas Cook & Son advertised to the public as a place of healing. Though it is 450 miles from Cairo, “Luxor… owes its importance to the fact that it is situated close to the ruins of the ancient city of Thebes.” He describes the Temple of Luxor, the Temple of Karnak, and the Temple of Mut as the “principal objects of interest” on the east side of the Nile. While each of these locations are “essential” for tourists to visit, the guide emphasizes the grandeur and impressiveness of the Temple of Karnak stating, “the ruins of the buildings at Karnak are perhaps the most wonderful of any in Egypt, and they merit many visits from the traveller.” The guide reinforces this point, with seven maps detailing the ruins of Karnak and their connections to dynastic Egypt. On the west bank, the principle locations of interest are the Temple of Kurnah, the Ramesseum, the Colossi, the village of Medinet Habu, the Temple of Ramesses III, and Der el-Bahari. The guide describes the Temple of Kurnah, the Ramesseum, and the Colossi as ornate and somewhat imposing structures, given their detail and magnitude. However, he states that Medinet Habu is worth visiting, given how a small group of Christians established a village around the ancient Egyptian temple in which they “carefully plastered over the wall sculptures… [and] used it as a chapel.” Throughout the guide, Christian practice in particular is emphasized, with the author consistently encouraging tourists to visit Christian churches, which could limit the scope of a visitor’s experience to one specific culture within ancient Egypt. Similarly to the Temple of Karnak, the guide declares the Temple of Rameses III “worthy of several visits,” given the opulence of the columns, displays of weaponry, and art. Lastly, the guide notes that Deir el-Bahari is worth visiting given the “fine marble limestone… used in its construction” and the that the “wall sculptures are beautiful specimens of art.” The curated areas that Thomas Cook’s guide emphasizes appear to be chosen for their visual and aesthetic appeal, as often highlight the ornate architecture and grandiose artwork that many find particularly captivating.

To the right is an example of these travels laid out in a chronological order.

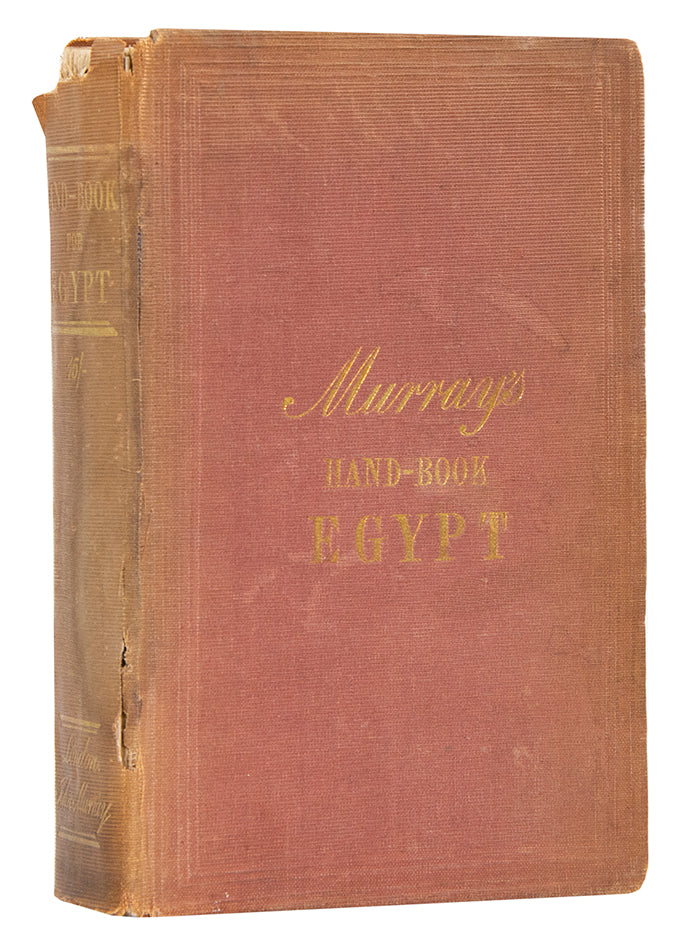

Other Egyptian Travel Guidebooks

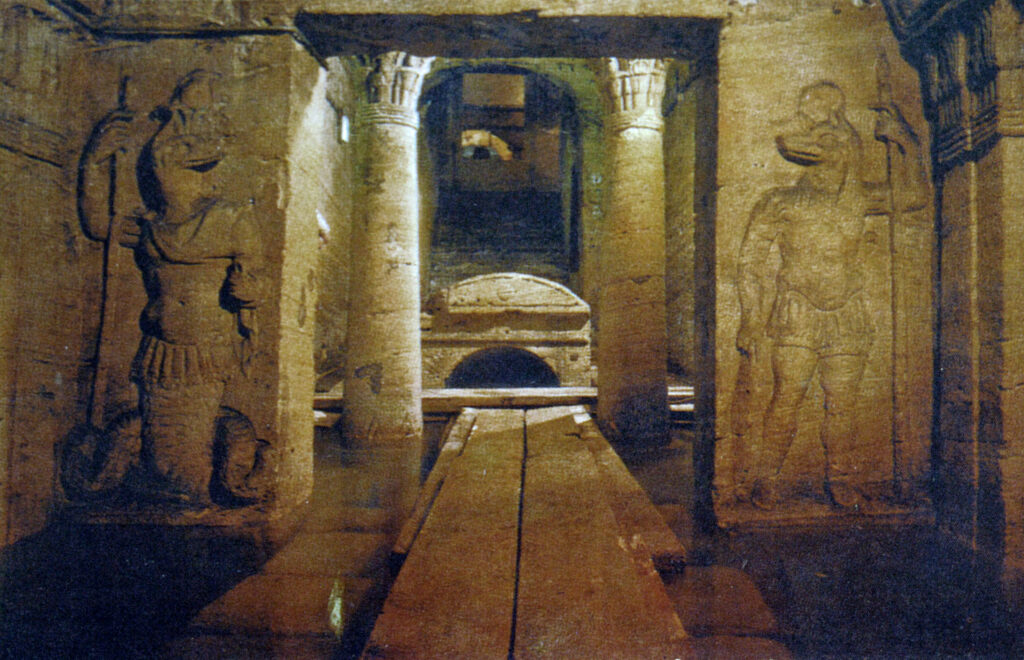

Murray’s handbook on Egypt, originally published in 1835, was among one of the first guidebooks published for Egypt. Murray’s guide offers more than the Thomas Cook guide in the ways of activities in Alexandria. He states that upon arrival in Alexandria one will find “excellent European shops of all descriptions standing amongst Eastern coffee-houses and bazaars.” He encourages travelers to visit the catacombs as “nothing which remains of Alexandria attests its greatness more than these Catacombs.” Murray’s guide also includes a list of helpful locations, from where to find a good breakfast, to physicians that speak English in the case of an emergency. Murray’s guide gives recommendations similar to the Thomas Cook & Son guide for travelers in Luxor and Cairo, though giving more details about local physicians and restaurants there along with some other helpful details. Overall, Murray’s guide aims to alleviate the concerns of potential travelers by outlining a variety of helpful locations and amenities for tourists.

Baedeker’s guide is similar to Murray’s guidebook to Egypt as it also emphasizes locations such as physicians or travel offices (specifically the locations of the Thomas Cook & Son offices) to help travelers in emergencies or in need of assistance with their travel accommodations. Baedeker also suggests that tourists visit one of many churches, gardens, or museums in Alexandria.

Baedeker’s guide, like the Thomas Cook guide, suggests that while there are locations one could visit in Alexandria, they are not worthwhile. For example, it describes the Alexandrian Museum of Graeco-Roman Antiquities collection as “intrinsically somewhat unimpressive.” Baedeker also provides a list of practical locations for Luxor and Cairo, as similarly mentioned in Murray’s guide. Baedeker also provides an extensive list of activities in Cairo.

In summary, each of the guides creates a detailed itinerary for travelers, though more extensive for Cairo than Alexandria. Where the Thomas Cook guide focuses on the historical context of Egypt’s monuments and artifacts, Murray and Baedeker’s guides focus on alleviating the difficulties associated with travels by providing helpful related to transportation, accommodations, meals, etc.

Egyptian Hotels

There were a variety of hotels that sprang up along with the boom of tourism in the late nineteenth century. While there were hotels that marketed to each class of people, several grandiose hotels emerged which aimed to serve the elite and wealthy travelers arriving in Egypt.

San Stefano: One such hotel is the San Stefano hotel and Casino in Alexandria, and it was a favorite place to promenade among the local elite. The building faced the ocean and featured a wide veranda upon which visitors could dine. For those who preferred indoors, there was a restaurant, ballroom, billiard room, and a club reading room for guests to enjoy. Despite its initial popularity, in 1993, the owners sold the hotel, and it ultimately closed to guests. Demolition occurred later that year. The photo to the right depicts the facade of the hotel, with the elaborate structure and tree and plant-lined path leading to the entrance.

Hotel Cecil: Another prominent Alexandrian hotel was the Cecil, which overlooked the sea and park. It featured a restaurant, hair salon for both men and women, billiard room, bar, and fireplace lounges. The hotel advertised that each room had its own bath, toilet, and telephone. However, this hotel’s 1930 opening was an ill-timed debut given the state of the global economy. The Hotel Cecil, like the San Stefano, was sold, but it remains open to guests, though with some alterations because of the hotel’s refurbishment. The photo to the right depicts the historic hotel’s facade with balconies at each room and trees decorating its lawn.

Shepheard’s Hotel: In Cairo, Samuel Shepheard founded the famous Shepheard’s Hotel in 1841. Though it was later sold to Philip Zech. Over its lifespan, the hotel was rebuilt four times and relocated three times. As such, tourists can no longer pay a visit to the historic version of the hotel, but the modern version that exists today. Though it began humbly and somewhat austere in structure, the hotel grew in popularity and transformed into a glamorous hotel (340 bedrooms with 240 bathrooms, plush music rooms for guests to lounge in, eccentric art decorating the lobbies, and extensive front terrace for guests to dine at) and hotspot for the elite and famous traveling through Egypt. Thomas Cook & Son would eventually set up offices within popular Egyptian hotels such as the Shepheard’s hotel to offer assistance to Cook’s travelers staying in those locations. The elaborate decoration, structure, and amenities continues to draw visitors to Shepheard’s hotel. The Shepheard’s Hotel is among the most iconic of the hotels in Egypt.

Gezira Palace: Elsewhere in the city, the Gezira Palace was originally designed as a palace for Napoleon III’s wife, the Gezira palace was sold in 1890 and converted into a hotel. It boasted electricity, 250 bedrooms, a ballroom and theater, and large gardens. The furnishings of the hotel were lavish and costly, aiming to appeal to American and European elites. As of the 1970s, the hotel was taken over by Marriott and operates as a hotel and casino. Tourists interested in the Geizra Palace can still visit the hotel, though it is under a different name and has undergone some refurbishment.

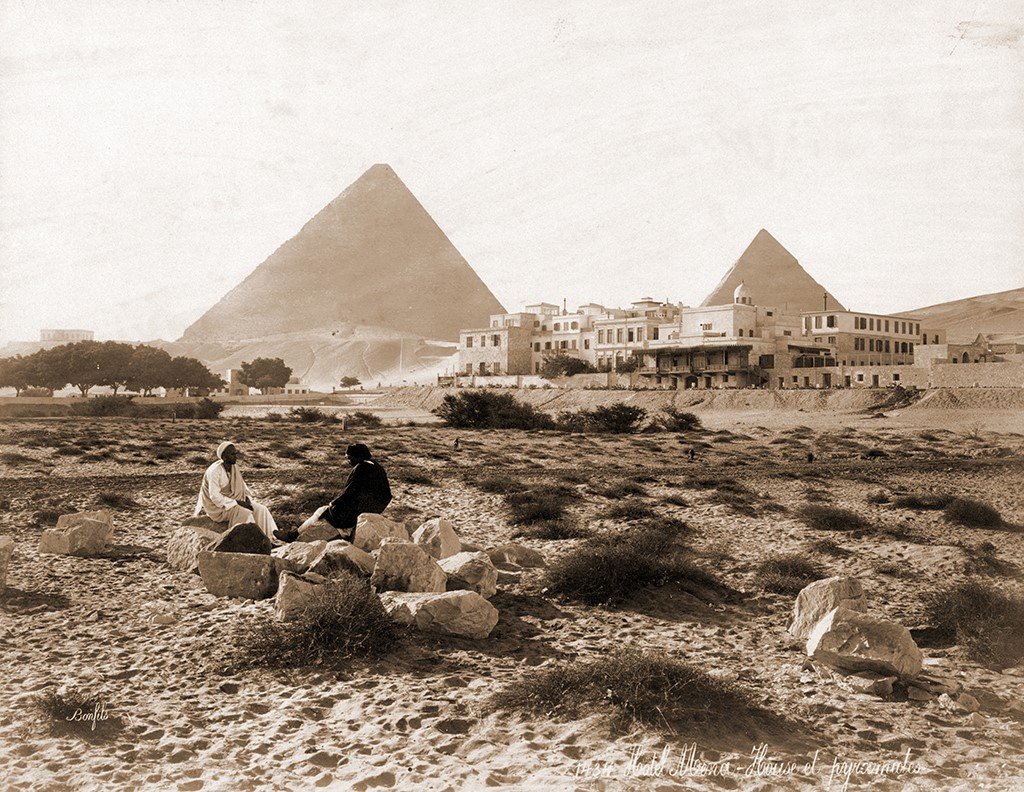

Mena House: The Mena House hotel, also in Cairo, was first constructed with the intention of shortening the distance travelers had to go in order to view the pyramids (originally a two-day excursion). As such, the pyramids can be clearly seen from the hotel, with each bedroom facing them. The hotel had a darkroom, billiard room, reception rooms, library, central dining space, and an art studio. The photo on the right exemplifies the close proximity of the Mena House Hotel to the pyramids in Giza.

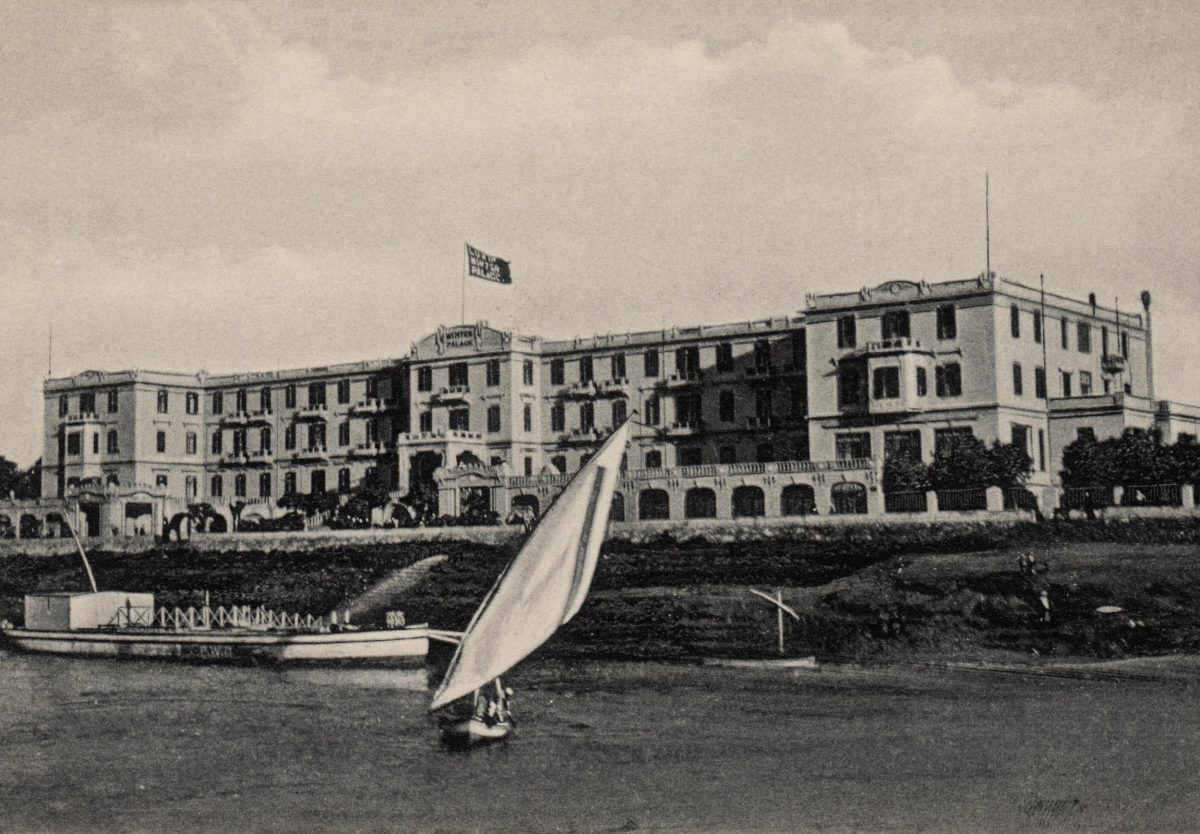

Winter Palace: The Winter Palace is located further south in Luxor, and rose to popularity with the discovery of the Tomb of King Tut. Its lavishness but its convenient closeness to the discovery attracted new clientele. Though Luxor was home to several hotels at the time of the Winter Palace’s construction, none were aimed toward the upper-class or elite residents in the way that the Mena House or the Shepheard’s hotels in Cairo did. Nearly each room of the hotel featured a balcony, and the hotel itself had a saloon, grand entrance hall, and extensive terrace. The photo on the right depicts the grandeur of the hotel from its size to the balconies at each room. The Hotel also features a grand staircase leading up to its entrance.

Each of these hotels attracted customers on an international scale, with some growing to such popularity that they have become landmarks of Egypt or “must see” destinations. Many of these hotels remain open today, which exemplifies the enduring popularity of Egyptian tourism and conveys how the allure and mystery of Egypt continues to manifest itself in the present. The fact that the hotels of Alexandria are the only few to have closed their doors to tourists furthers the notion that Alexandria was not a popular destination among those travelling to Egypt, hence these hotels’ inability to withstand the test of time as their Cairo and Luxor counterparts did.

Impacts of Tourism

Though the tourist boom provided benefits to the Egyptian economy through the aforementioned increases in the job force, and gave the wider world access to the wealth of knowledge of Egyptian history, it also led to the destruction and loss of important monuments and artifacts. Unfortunately, there was little control over tourists visiting ancient monuments, and many tourists would often deface or remove parts of walls in temples and tombs as mementos of their adventures in Egypt; some travelers would loot monuments and sell their stolen goods to the highest bidder. One such tourist, Amelia Edwards, collected more than 3,000 Egyptian antiquities in her excursions to Egypt, and rumors suggest she even kept two ancient Egyptian heads in her bedroom closet. E. A. Wallis Budge, the author of the Thomas Cook & Son guidebook, engaged in looting himself. Budge first visited Egypt on a collecting trip in 1886, where his illegal agents cleared tombs, though a majority of these tombs had already been raided once before. Despite this, Budge amassed a collection of Egyptian artifacts. While it might seem extreme, Budge’s activities were not atypical of many European museum officials of the time, with a significant portion of the goods he collected being sent to the British Museum. The innate desire to collect collect antiquities and other objects of the ancient world is little understood but devastating to the maintenance and preservation of ancient history, but as long as there is a demand for these goods, people will continue to fill the gap regardless of its impact on historical conservation. Despite the great number of stolen goods, Egypt would continue to draw curious visitors from around the world until tourist companies realized the financial importance of Egyptian artifact and monument preservation, as the potential to see such awe-inspiring artifacts and structures drew in tourist groups.

Images sourced from the library of congress (photos of the Winter Palace, Shepheard’s Hotel, Mena House, Port of Alexandria, and the maps of Egypt) creative commons, the Shapell Manuscript Foundation (Cook’s Nile Poster) and Hazuzu (Nile Steam Ship Ticket).