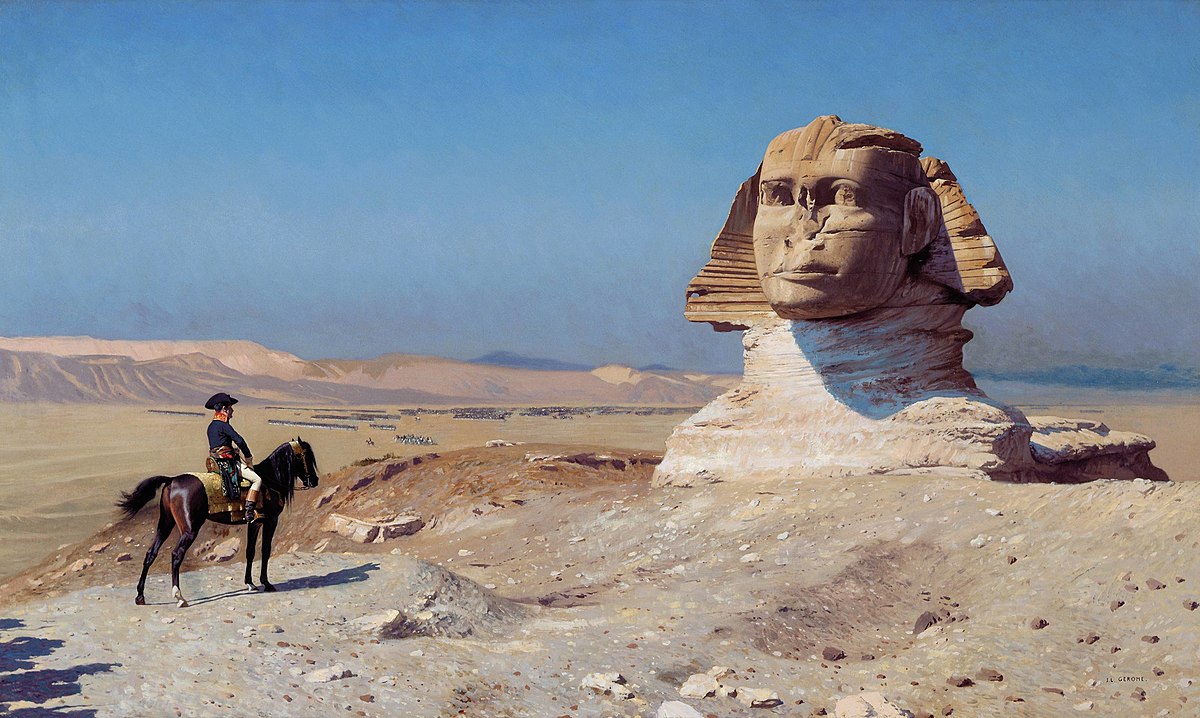

Above: Gérôme, Œdipe/Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, 1886, oil on canvas.

Who was Jean-Léon Gérôme?

Jean-Léon Gérôme was an Orientalist painter who was born in May of 1824 to two working-class parents in Vesoul, a small town in eastern France. He started taking drawing classes in school at an early age, and after several years, he also started taking classes in painting. After finishing his education, he moved to Paris in 1840—still a teenager—to pursue a career in painting. Gérôme also spent time in Rome when he was 18 as his painting career began. Later in life, he was a member of some of several French Salons and eventually became president of the Society of French Orientalist Painters just before the turn of the 20th century.

Origins of Orientalist art

In the art-historical context, Orientalism refers to “a genre of painting, pioneered by the French… with predominantly Middle Eastern and North African subjects…” (MacKenzie 1995). The genre of Orientalism developed in the mid-19th century around the same time as the genre of Realism, which also became popularized in France, and Impressionism in the 1870s. In Gérôme’s paintings of Egypt, Egyptians are portrayed through their appearance as other, inferior, and uncivilized. French Orientalist art more broadly also perpetuates gendered stereotypes, including an emphasis on the potential for violence by Egyptian and Arab men.

Gérôme in Egypt

Gérôme traveled to Egypt seven times, and he visited Egypt first in 1857. In the decades following the French invasion of Egypt and the beginning of French imperialism there, travel to Egypt became very popular within the upper and middle classes of Europe, particularly in Britain and France. The Description de L’Egypte also contributed to Egypt’s popularity as a travel destination. For travellers, one of the fastest and most convenient ways of getting around was traveling down the Nile and seeing Egypt by boat. Gérôme did just this: in his autobiography, he wrote that he spent four months on a sailboat going down the Nile, painting, hunting, and fishing, and spent some more time in Cairo near the end of his visit.

Painting, photography, and framing

In The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme: With a Catalogue Raisonne, Gerald M. Ackerman writes that “travelling to exotic lands had become much more common and perhaps easier than twenty years before when Gérôme first went to Egypt” (92). When Western travellers would visit Egypt, one of the things that more and more people started bringing was a photographic camera. In the 1850s and 1860s—around the time of Gérôme’s first visit to Egypt—this was still a fairly new technology; however, as it became more popular, people started bringing cameras with them to be able to take pictures of what they saw and take home memories from their travels. For artists, this became particularly useful: they could refer back to these photographs later on to inform their paintings. Gérôme and others of his Orientalist contemporaries relied on photography, at least some of the time, as the foundation for their painting.

One of the common elements that photography and painting share is staging, also known as framing—how the composition is arranged. Framing was something that Orientalist painters consciously manipulated: if the viewer believes that a painting is an accurate representation of a photograph, and if they also believe that the photograph is an accurate representation of reality, they might accept that the artist is painting a scene completely objectively, which is never the case.

Gérôme often paints in fine detail to make his work more convincing for the viewer. In Prayer in the House of the Arnaut Chief (above) and the Carpet Merchant, this detail shows up mainly in clothing and architecture. As Roger Benjamin writes in Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa, 1880-1930, “Orientalist painting relies on the successful control of costume—not only the clothes sitters happen to wear, but the whole ‘science’ of using dress to make an image more convincing” (174).

.jpg/1200px-Jean-Léon_Gérôme_-_Evening_Prayer%2C_Cairo_(1865).jpg)

Additionally, framing also becomes paramount because it informs who or what the viewer sees (or doesn’t see); the viewer’s perspective is entirely determined by the artist. Gérôme and other French Orientalist artists always had control over not just the content but the framing of their artworks. In many of his paintings, Gérôme’s realism can create a false sense of reality for the viewer (at the time, Europeans who, by and large, hadn’t traveled to Egypt themselves) that was reinforced in the Orientalist genre.

Orientalist painting relies on the successful control of costume—[…] the whole ‘science’ of using dress to make an image more convincing.

Roger Benjamin, Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa, 1880-1930 (University of California Press, 2003), 174.

Orientalism and French imperialism

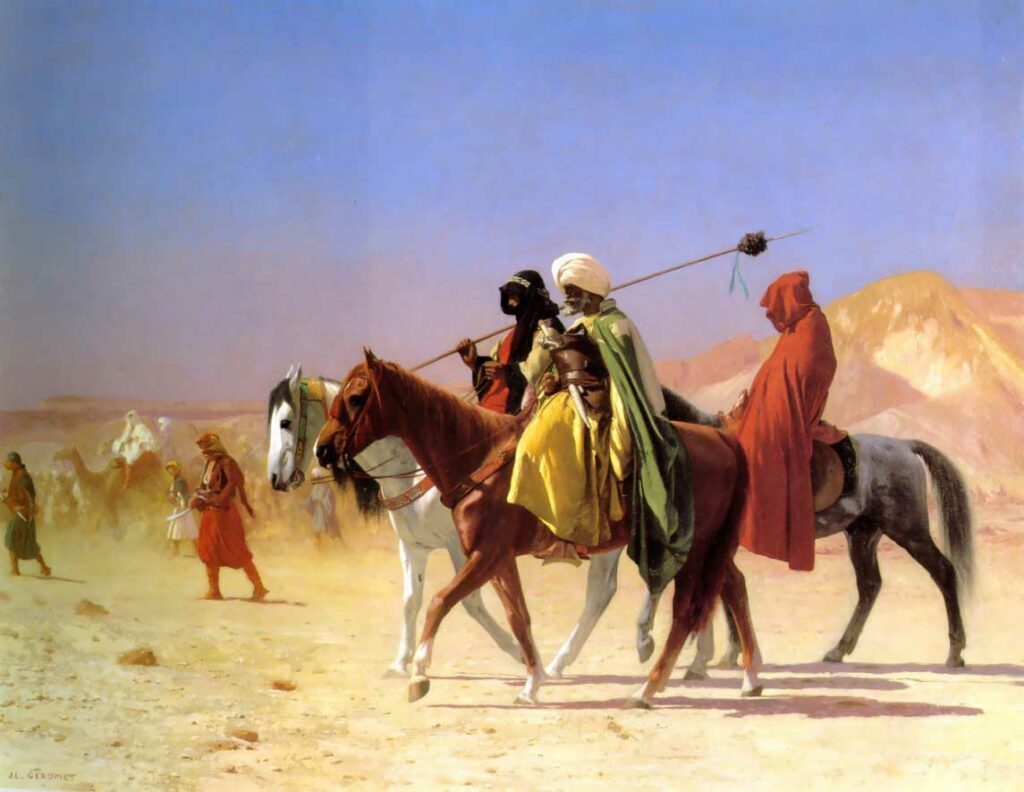

One of the contrasts that Gérôme amplifies through his painting is the inferiority of Egyptian culture and history versus the superiority of the French and their imperial presence in Egypt. Orientalism as a genre elevates and glorifies European power while at the same time othering and exoticizing non-Western peoples and cultures. In several of his paintings he depicts the French in Egypt, focusing particularly on his representation of Napoleon as a dominant figure of French imperialism. In Napoleon and His General Staff in Egypt (below), Napoleon and the reset of his French staff ride camels through the desert. Napoleon might be the person the viewer looks at first because of how the eye is drawn upward on a slope from either side. The only other person who is relatively in the foreground is an Egyptian man who is looking upward at Napoleon, which seems to further emphasize European power and dominance in Gérôme’s portrayal of Napoleon.

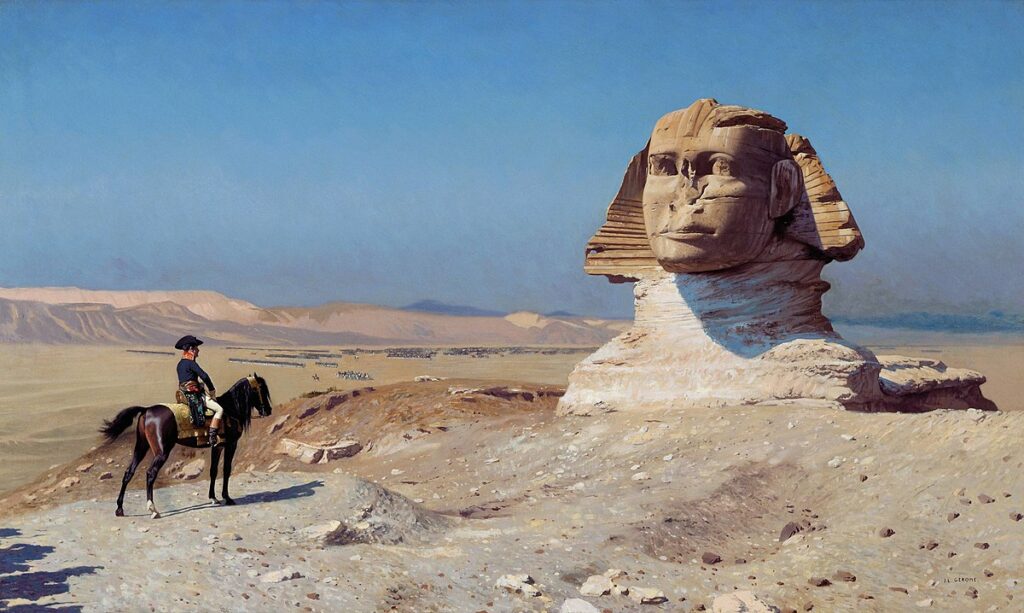

Similarly, in Napoleon Before the Sphinx (below), the viewer encounters another depiction of Napoleon, this time on horseback, facing the Sphinx, with the French army in the background. Throughout history, ancient Egypt and its history has been seen as valuable to control and even to have ownership of. In this painting, it feels like Napoleon is engaging with ancient Egyptian monumental architecture, and ancient Egypt more broadly, in a way that suggests he might see himself as having the powers of a pharaoh. In this way, Gérôme co opts ancient Egyptian history to reinforce the worldview and values of French imperialism.

If Napoleon Before the Sphinx looks familiar, that might be because it’s recreated in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (2023) (below). In this scene, it seems like the movie is trying to replicate Gérôme’s painting to achieve a similar artistic effect.

Takeaways

In the paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme, and in the art of 19th century French Orientalistm more broadly, these artists used Egypt as a setting in order to map European imperialism and colonialism onto the Egyptian landscape. Gérôme and his contemporaries manipulated elements like framing to control the viewer’s perspective, and the end result is that within these paintings, Egypt becomes a sort of exoticized fantasy world for the viewing pleasure of European audiences.

Check out the pages below to learn more from the Presenting Egypt cluster!

Bibliography

Ackerman, Gerald M. The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme: With a Catalogue Raisonne. Sotheby’s Publications, 1986.

Ali, Isra. “The Harem Fantasy in Nineteenth-Century Orientalist Paintings.” Dialectical Anthropology 39, no. 1 (March 2015): 33-46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43895901.

Baldassarre, Antonio. “Being Engaged, Not Informed: French ‘Orientalists’ Revisited.” Music in Art 38, no. 1-2 (Spring-Fall 2013): 63-87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/musicinart.38.1-2.63.

Behdad, Ali. Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Benjamin, Roger. Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa, 1880-1930. University of California Press, 2003.

Burney, Shehla. “CHAPTER ONE: Orientalism: The Making of the Other.” Counterpoints 417, PEDAGOGY of the Other: Edward Said, Postcolonial Theory, and Strategies for Critique (2012): 23-39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42981698.

Curran, Brian A. “Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730-1930.” The Art Bulletin 78, no. 4 (December 1996): 739-745. https://login.proxy048.nclive.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/artshumanities/scholarly-journals/egyptomania-egypt-western-art-1730-1930/docview/222969638/sem-2?accountid=10427.

Hamrat, Fatima Zohra. “Photography and the Imperial Propaganda: Egypt under Gaze.” Cultural Intertexts 11 (2021): 84-99. https://login.proxy048.nclive.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/artshumanities/scholarly-journals/photography-imperial-propaganda-egypt-under-gaze/docview/2617716904/sem-2?accountid=10427.

MacKenzie, John M. Orientalism: History, theory and the arts. Manchester University Press, 1995.

Mortimer, Mildred. “Re-Presenting the Orient: A New Instructional Approach.” The French Review 79, no. 2 (December 2005): 296-312. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25480203.

Parry, James. Orientalist Lives: Western Artists in the Middle East, 1830-1920. The American University in Cairo Press, 2018.