Within this webpage, one will be able to learn about how Egyptian Revival Style architecture was subverted and used by US architects and applied to prisons and monuments to imbue themes of power and immortality into the buildings.

First, I explain how architecture is an inherently active form of persuasion and art before diving into what is and why Egyptian Revival Style architecture in the US in the early 1800s. Then, I write about prisons and monuments before concluding with architecture’s power and importance then and now.

But first, architecture is not passive.

Now, you might not be interacting with the Washington National Monument or the Groton Monument or the New Jersey State Penitentiary on your day-to-day, week to week, monthly, yearly basis, or even ever…. but most likely you go to the grocery store. To think about architecture as active and persuasive, think about how you interact with space in the grocery store. Fresh fruits and vegetables are positioned at the front of the store whereas staples like eggs, bread, and milk are placed at the back—requiring shoppers to traverse the entirety of the store. Further, impulse items like chips or candies are often right next to or near registers so people add them on as last minute purchases. In short, grocery stores are designed for their purpose: consumption. So, when thinking about architecture, think of it not as passive but as interactive and trying to persuade people of ideologies, ideas, etc.!

“We shape our buildings: thereafter they shape us”

– Winston Churchill, October 28th, 1943

Below, there are three different examples of Egyptian Revival Style architecture from around the world. To the left, is an elephant enclosure at the Antwerp Zoo in Belgium, the middle gates outside of St. Petersburg, Russia, and to the right a synagogue in Tasmania. These different structures highlight the breadth and depth of applications and cities Egyptian Revival Style architecture has been used.

Now what exactly is Egyptian Revival Style architecture? Like identifiable above, Egyptian architecture is distinguishable. Below are different aspects of Egyptian Revival style architecture.

Arched windows

Cavetto style cornices

Flat roof

Massive columns

Recessed porches

Vulture and sun disk symbol

The emergence of Egyptian revival Style Architecture

Below, I explore two different types of Egyptian Revival Style architecture. I write about both prisons and monuments by connecting them through themes of power and immortality.

Prisons

In the 1830s, there were two main ideas on how prisons should operate: the Auburn system and the Pennsylvania/separate system. The main difference was the Auburn system had prisoners working together during the day but in different cells at night whereas in the Pennsylvania system incarcerated persons were separated every second of the day.

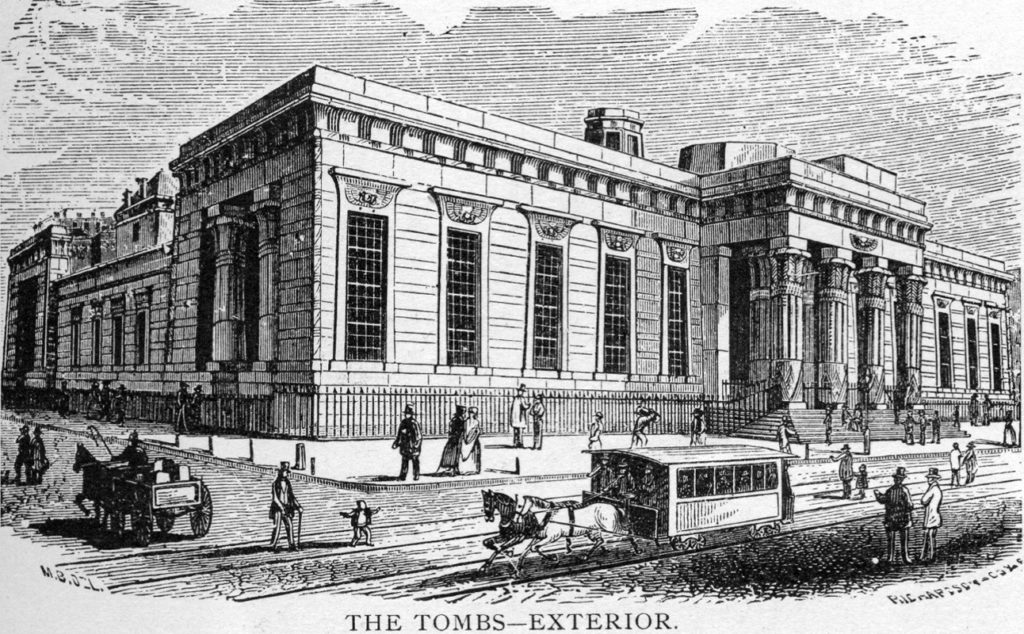

Architect John Haviland designed both the New Jersey State Penitentiary and the NYC Halls of Justice, later known as The Tombs, in Egyptian Revival Style. While not only more economical than the popular gothic style, he believed it would be a humanitarian style. Haviland believed that Egyptian Revival Style would evoke a deep sense of justice and wisdom—qualities the West associated with ancient Egypt—to encourage incarcerated people to focus on rehabilitation. James Elmes’ (John Haviland’s mentor) wrote about Egyptian Revival Style saying it was “immortality, sacred solemnity, and awesome grandeur.”

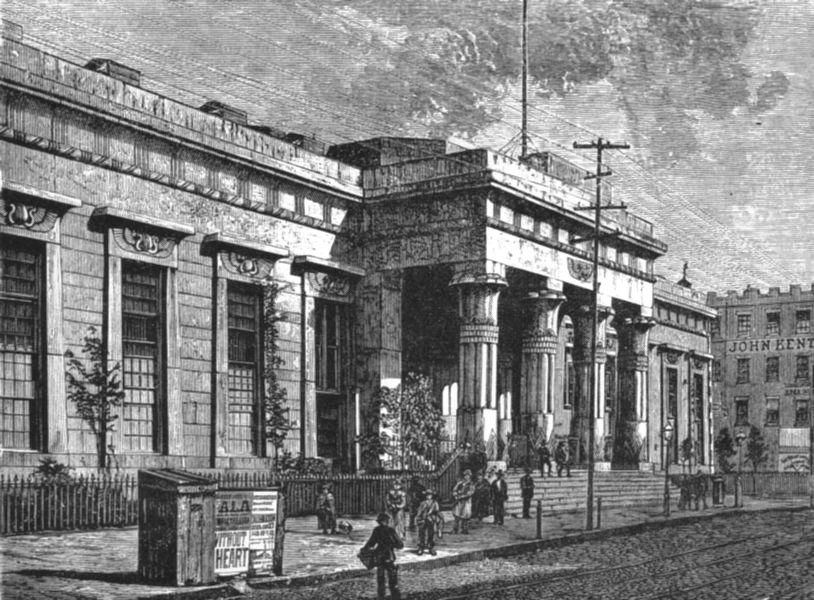

New Jersey State Penitentiary

Here, features of Egyptian Revival Style are embodied: flat roof, recessed porches, arched windows.

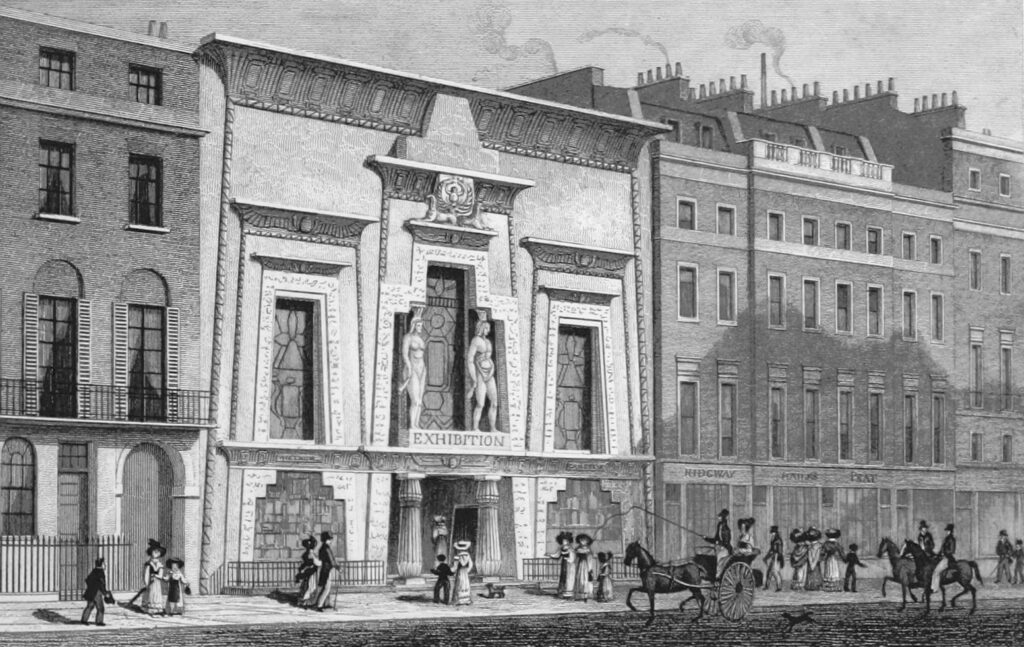

The NYC Halls of Justice “The Tombs”

In the New York City Halls of Justice, referred to as “The Tombs”, the structure highlights the importance of justice, wisdom, and rehabilitation. The prison was modeled after ancient Egyptian temples like Denderah. In ancient Egyptian temples, the center of the temple was the most important room because that is where the god lived. Mirroring this, in “The Tombs” the central room was the courtroom. This emphasized Haviland’s vision that Egyptian Revival Style would focus on rehabilitation. However, as read below, while these motives were altruistic, incarcerated people did not perceive Egyptian Revival Style architecture in the same way.

“The Egyptian character of the masonry weighed upon me with its gloom”

– Herman Melville, inmate at The Tombs

Monument & Memorials

Above are two obelisks, the Groton Monument (left) and Washington National Monument (right). Commonly used in ancient Egypt, obelisks are stone pillars used as landmarks or monuments honoring either gods or the pharaohs. In the US, obelisks gained popularity during the Rural Cemetery Movement (1833-1875) when attitudes toward death radically shifted from pessimistic to hopeful as well as ensuring that dead bodies were not buried in cities—a growing public health concern. In this newfound movement, obelisks found a place.

The obelisk and its connection to power and grandeur—built from its roots in ancient Egypt—was meant for commemoration. Obelisks in the US were unique in the sense that they had staircases inside of them and people could travel to the top and look out across the plains and territory. This imbued power into the monuments because people could see the surrounding land, a metaphor for Manifest Destiny, Westward Expansion, and the future of the US.

The Groton Monument, commemorating the deaths of US revolutionary soldiers at the hands of the British at the Battle of Groton, stands 134 feet tall. The height and grandeur of the obelisk immortalizes the sacrifice and memory of the revolutionary war soldiers.

Groton Monument finished in 1830.

Washington National Monument started in 1798 and finished in 1884.

The Washington Monument becomes a particularly inspiring and profound example of power and immortality in monuments. Ideas for the Washington National Monument started following George Washington’s death in 1799 but the obelisk was eliminated as a potential design in 1816. However, in 1825 architect Robert Mills decided the design WOULD be an obelisk because of its “lofty character, great strength… [and] degree of lightness and beauty” which represented Washington and the United States. Further, the obelisk is for only Washington, likening him to the power and significance of a god or pharaoh. In Burkean emotions, the idea of an obelisk can be connected to a phallus, representing George Washington as the father of the US.

However, the building of the monument would fail to be finished until 1884 because of the Civil War and the bloodshed that devastated the United States. Following the end of the Civil War, the call to complete the monument became not only about George Washington and him unifying the country long ago but about the monument representing the nation itself. Since the monument was left unfinished before the Civil War, finishing the monument symbolized the restoration of the nation.

“Let the column which we are about to construct, be at once a pledge and an emblem of perpetual union! Let the foundation be laid, let the superstructure be built up and cemented, let each stone be raised and riveted, in a spirit of national brotherhood!”

– Robert C. Winthrop, Speaker of the House of Representatives

What We Build From Here: Conclusions

Egyptian Revival Style architecture has been co-opted by the United States to enact their specific purposes—whether for more humanitarian style prisons, identity building, and more.

Moreover, architecture is important as it both consciously and subconsciously influences people’s belief and perceptions. Whether Egyptian Revival Style, Classical, Gothic, or more, architecture is trying to convince people. While not inherently bad, people should be aware of the ways architecture shapes people’s experiences with space to be more critical and thoughtful of the world around them.

Egyptomania 2025

Created by students in HIS 372