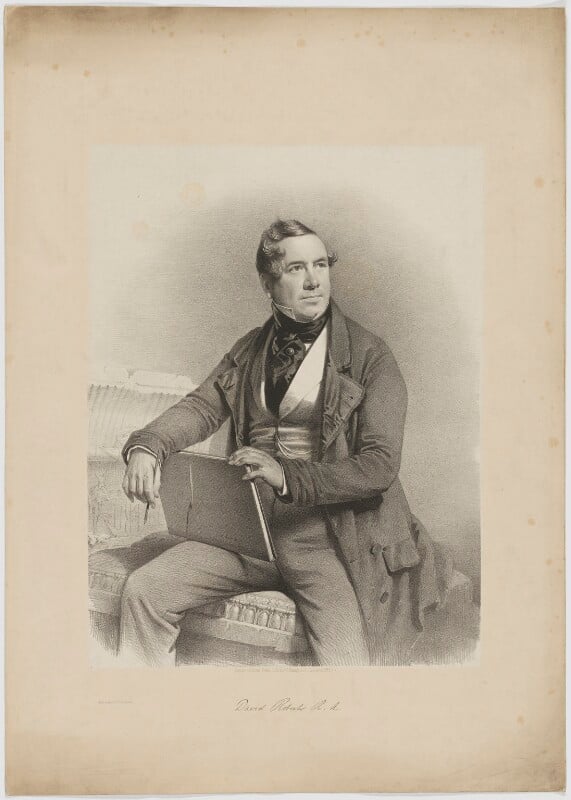

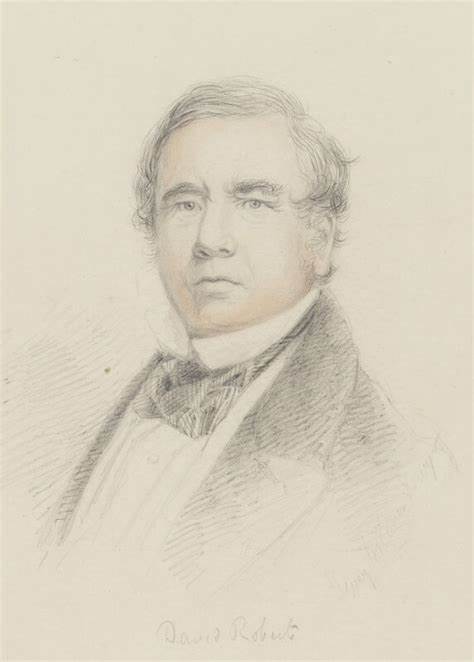

Who Exactly is David Roberts?

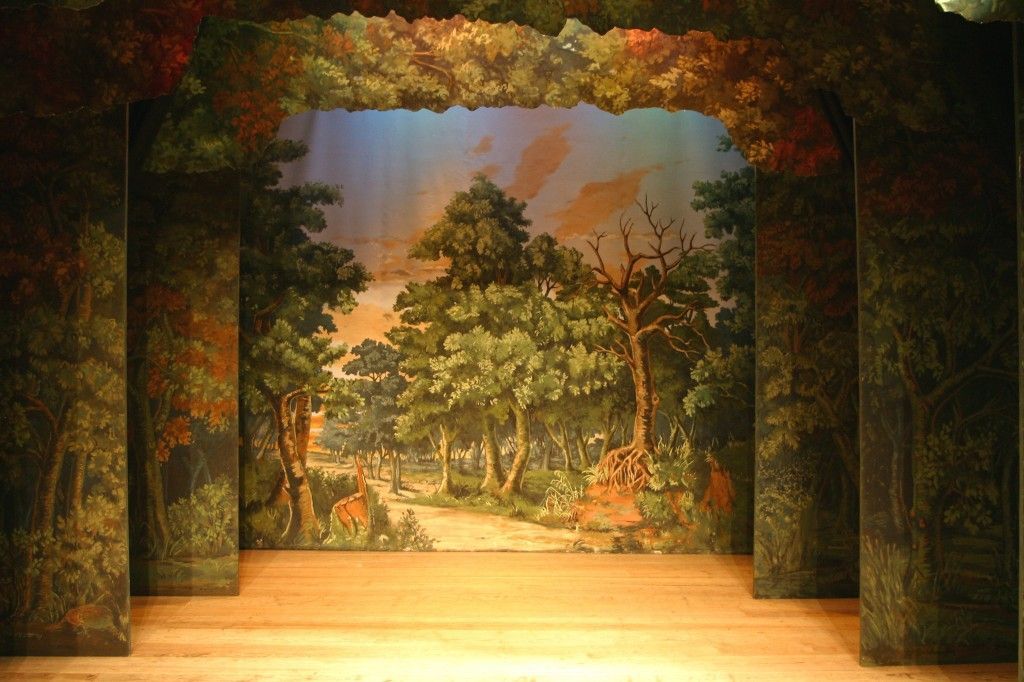

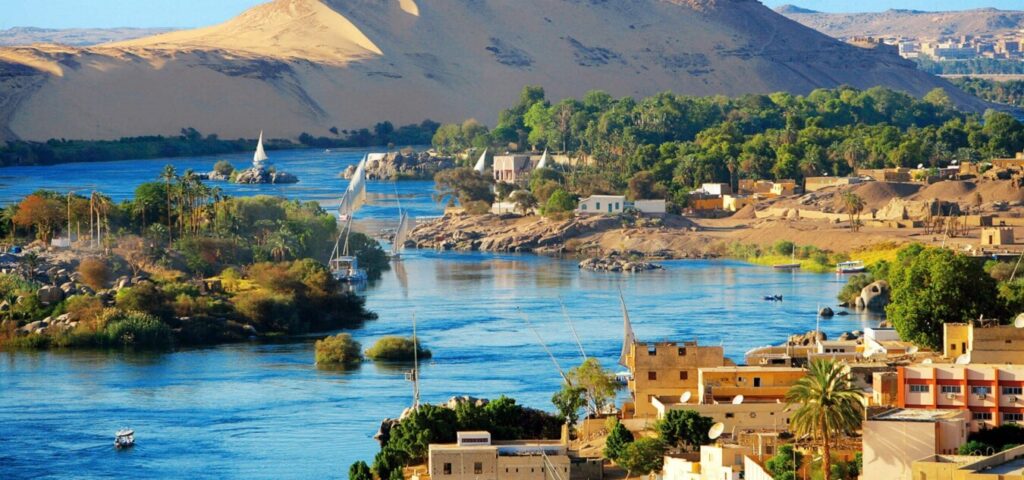

David Roberts (1796–1864) was a Scottish painter who rose to fame primarily due to his depictions of prominent Middle Eastern regions. Born in Edinburgh, Roberts began his career as a simple painter, often taking jobs in the theatre creating scenic backdrops. These early experiences helped shape and refine his distinctive artistic style that would later characterize his representations of the Middle East. In 1838, Roberts embarked on an extensive journey, studying and sketching various regions within Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Arabia, Idumea, and Nubia. During his time there, he meticulously documented architectural and natural wonders of the lands. Upon returning to Europe, Roberts transformed his field sketches into paintings and lithographs, culminating in his acclaimed publication The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia. His travels, largely inaccessible to ordinary Europeans, were considered groundbreaking and contributed to one of the most significant collections of visual imagery from the region in the 19th century.

Biography of David Roberts Life

The History and context of Orientalism

What is Orientalism?

Orientalism, is considered to be a scholarly discipline that encompassed the study of the following: literature, religion, law, art and the philosophies of “Eastern societies”. On another hand, Orientalism is not only the study of these societies, but a discourse deeply rooted in the imperialistic plots that the West held against the East. As society has stepped into modern times, this term was no longer deemed appropriate and has been changed to a series of different names such as East Asian or Arab Studies. More commonly now, Orientalism is a term used to refer to the Western perspective or gaze placed upon the cultures and peoples of what’s considered to be the “Orient”.

What is “the Orient”?

The original term, “Orient” referred to the East, but whose East did this Orient represent? Research in the field of Orientalism revolved around subjects that were located in various different regions. In the mid-20th century, Western scholars considered it to be involving a majority of Asia- east, southeast, and eastern central. In the past, in the early 20th century, it often included North Africa as well.

Why is Orientalism bad?

Orientalism is problematic because it reinforces power imbalances and distorts the understanding of Eastern cultures. It reduces the vast and diverse societies of the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa into a single, stereotypical image—often exotic, backward, irrational, or dangerous. These simplified representations erase cultural complexity and dehumanize real people, turning them into flat characters in a Western narrative.

Edward Said’s Critiques on Orientalism

“The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.”

Edward Said

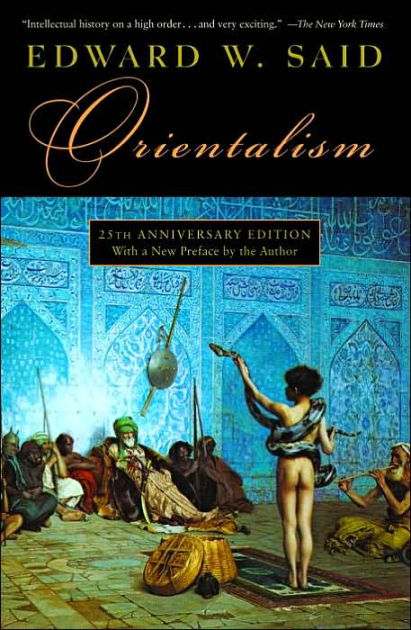

Some people may question why society has moved away from the term Orientalism to describe things particular to this specific area of study, but it’s all thanks to one leading voice who examined the Western scholarship of “the Orient,” specifically the Islamic World. Edward Said was a literary critic as well as political activist who was best known for his foundational book, Orientalism. In this seminal book, Said critiques the cultural representations that are the bases of Orientalism. In Orientalism, Said argues that Western academics and travelers held inherent biases and prejudiced interpretations that were shaped by the power dynamics of their time when approaching the study of Eastern societies. By making this argument, he disputes Orientalism as solely an academic field and redefines it as a structured system of ideas and attitudes through which the West has historically dominated the East. Said explains that Orientalism gave Europeans cultural and intellectual authority to speak on behalf of Eastern societies, silencing authentic voices and imposing a Western lens that claimed objectivity and universal validity. These representations weren’t neutral; rather, they reinforced ideas of Western superiority and were used to justify the colonial ambitions of European powers. Moreover, Said describes how Orientalism constructed what he called an “imaginative geography,” where the East was portrayed through visual and textual representations as exotic, timeless, and mysterious—ultimately serving Western consumption. These portrayals rendered the Orient as static and fundamentally different from the so-called progressive, rational West. His critique challenged scholars to reflect on their embedded assumptions and biases, urging more critical, ethical approaches when studying cultures different from their own.

David Roberts Work on “The Orient”

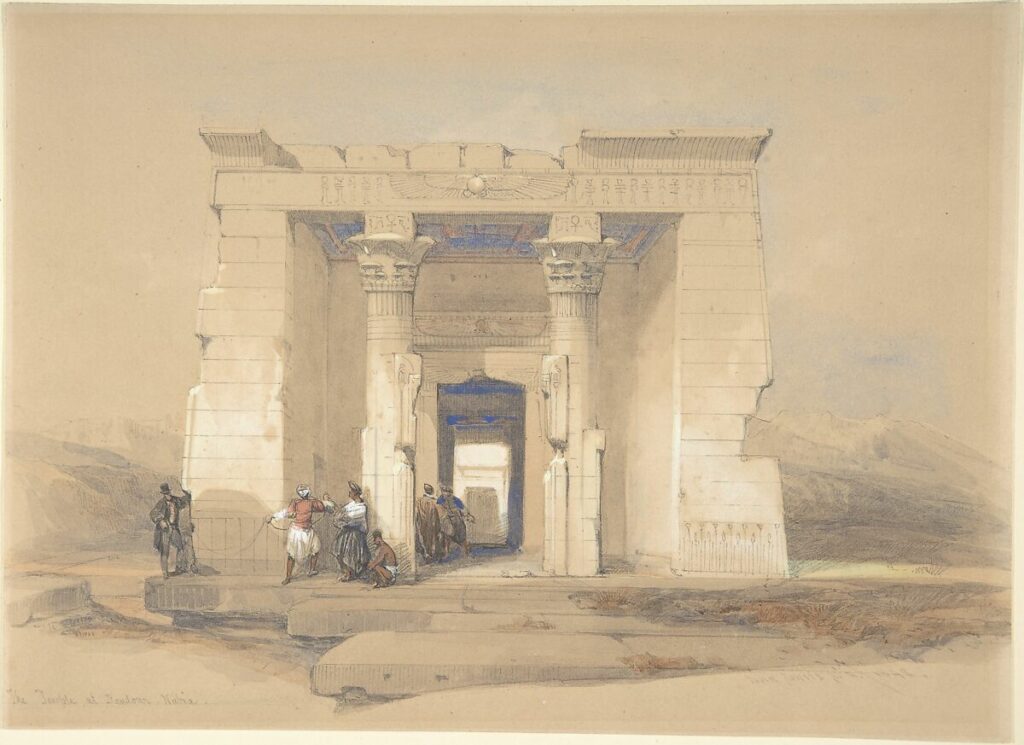

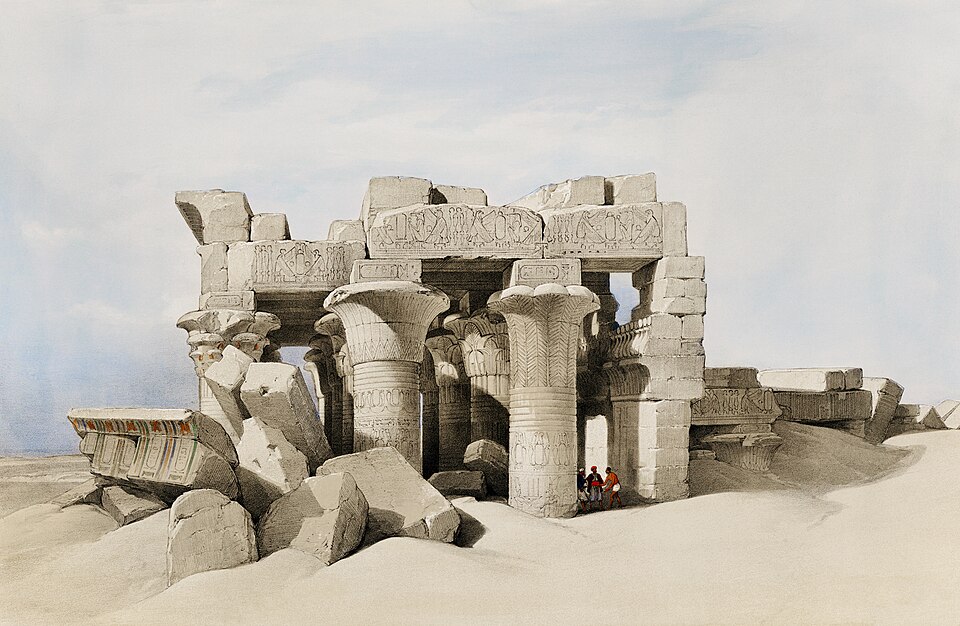

Title: The Temple at Dendur, Nubia

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1848

Medium: Watercolor and gouache (bodycolor) over graphite

Dimensions: 19.5 x 26.7 cm

Repository: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, NY

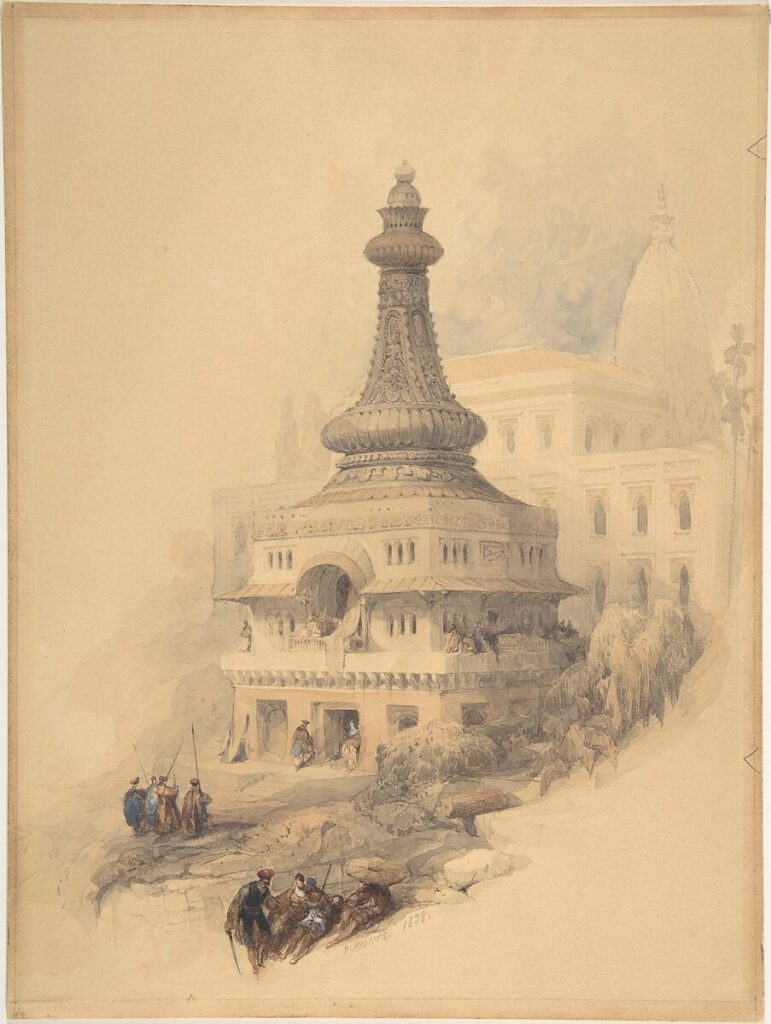

Title: Oriental Scene

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1838

Medium: Watercolor over traces of graphite on cardboard

Dimensions: 31 x 23 cm

Repository: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, NY

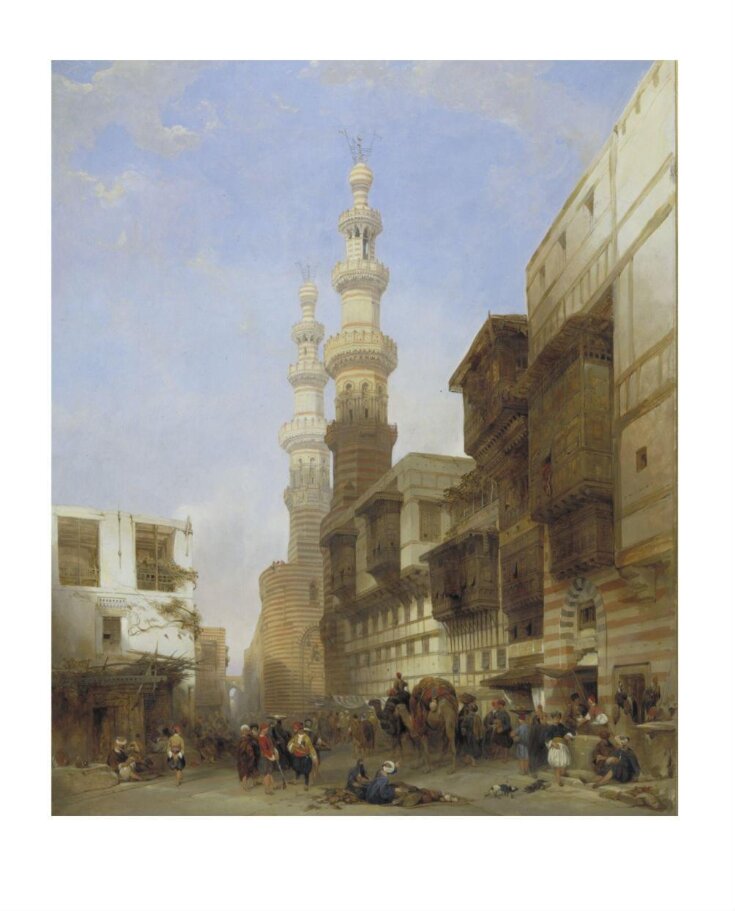

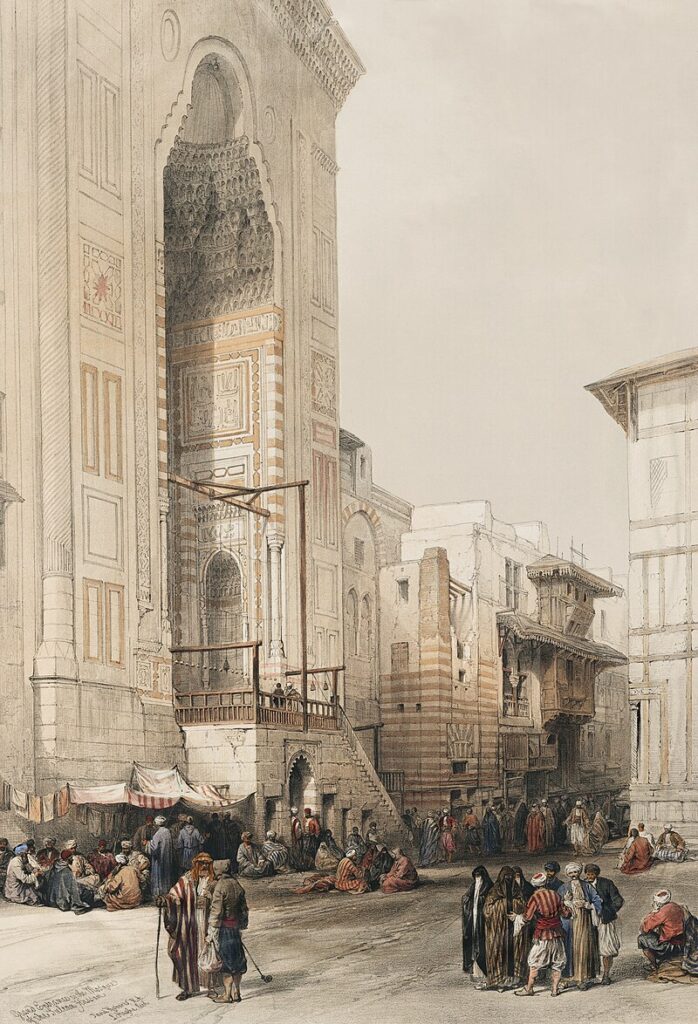

Title: The Gate of Metawalea

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1843

Medium: Oil on panel

Dimensions: 76.1 x 62.8 cm

Repository: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

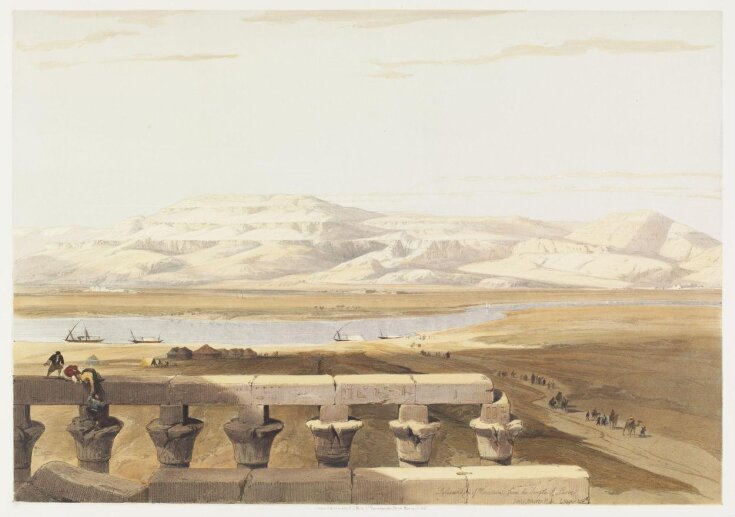

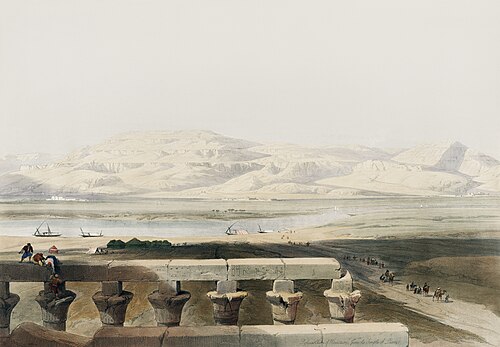

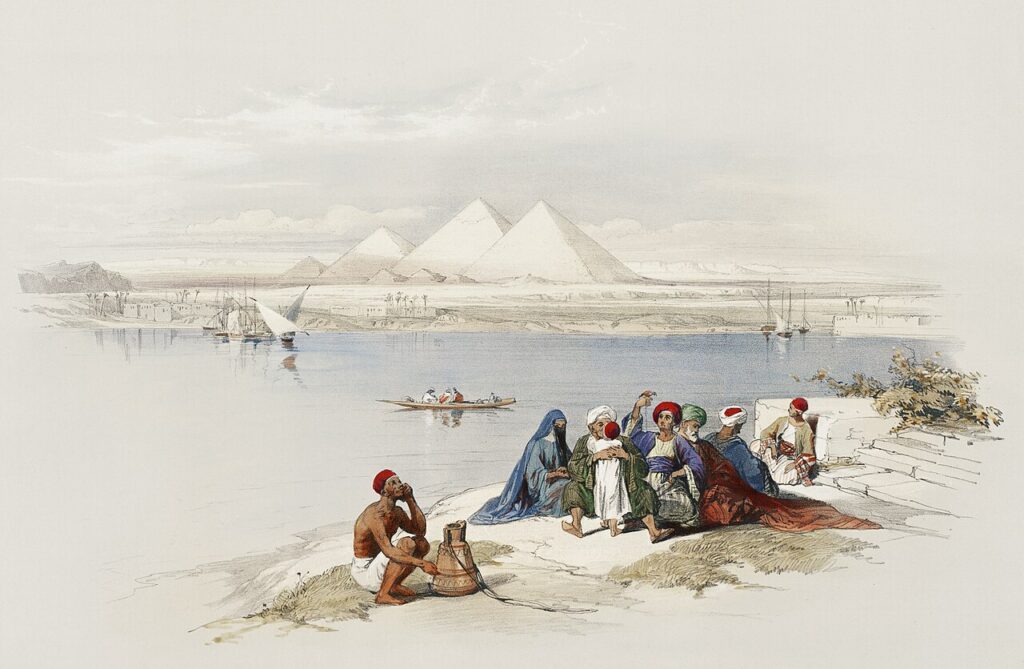

Title: Lybian Chain of Mountains, From The Temple Of Luxor

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1847

Medium: Lithograph, with two tint stones, coloured by hand

Dimensions: 35 x 50 cm

Repository: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

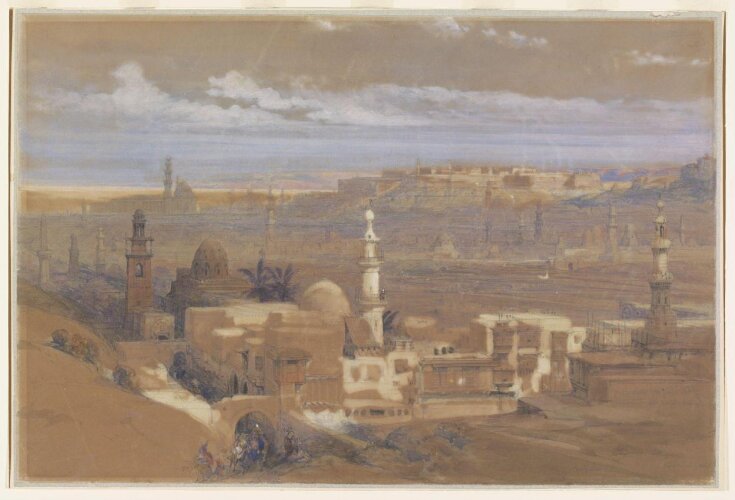

Title: Grand Cairo

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1839

Medium: Water- and bodycolour over pencil

Dimensions: 31.8 x 48 cm

Repository: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

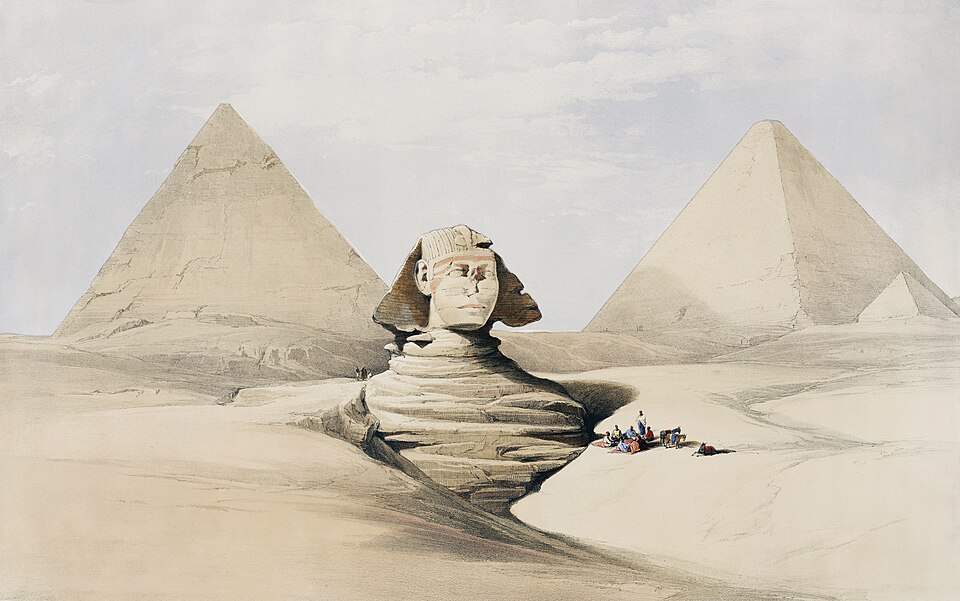

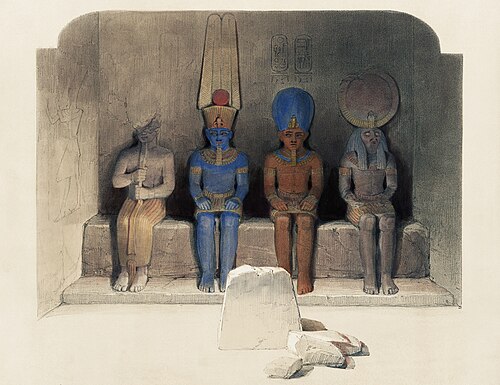

Key Orientalist Image Themes

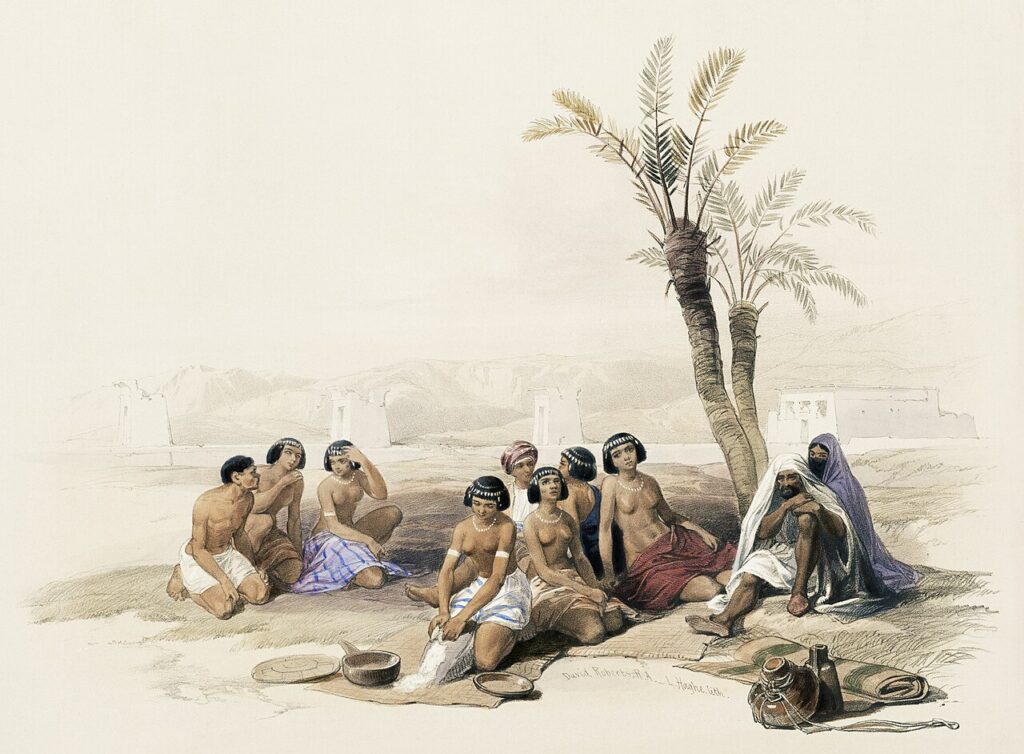

These are key examples of Orientalist visual culture, reflecting the 19th-century Western tendency to depict the Middle East as a timeless, exotic, and decaying region. A recurring theme in his work is the portrayal of ancient ruins and monumental architecture—such as the temples of Abu Simbel, Baalbek, and Luxor—which are shown in varying states of decay. Roberts also frames many sites through a biblical or religious lens, presenting locations like Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the Jordan River as sacred spaces filled with spiritual significance. This framing aligns with Christian European ideals and portrays the region as both mystical and in need of Western rediscovery. His emphasis on vast architectural scale, with human figures rendered small or insignificant, contributes to a sense of awe and otherness, invoking the Romantic sublime. Moreover, his use of shadow, dramatic lighting, and distant vantage points creates a picturesque aesthetic that romanticizes decay and implies a fallen grandeur. While Roberts does include local people in some scenes, they are often anonymous and depicted engaging in stereotypical or static activities, furthering the image of the East as exotic and culturally “other.” Through these visual choices, Roberts constructs not just a record of his travels, but a distinctly Orientalist vision of the Middle East that aligns with broader Western imperial ideologies of the 19th century.

Oversimplification of Egyptian Culture

In addition to his role in creating and enforcing colonial power dynamics onto Eastern societies, Roberts also frequently oversimplified Middle Eastern cultures in general, focusing predominantly on architecture and landscapes and conveniently neglecting the complex social, political, and economic realities of local populations. While yes, his artworks were praised for their accuracy in replicating sites and monuments, rightfully so, they drastically failed at providing insights into contemporary societal dynamics. In paintings such as “Temple of Isis on the Roof of the Great Temple of Dendera,” Roberts was able to reduce local figures to mere decorative elements within romanticized and idealized settings. By doing so, he completely ignores the contemporary lived experiences of these individuals and pushes that onto the European consumer. Roberts touched a bit on his thoughts regarding the public in the Middle East but I can’t quite figure out why he often avoided depicting scenes of everyday life or social interactions that would reveal the region’s contemporary vitality or complexity. But perhaps, maybe that was never his goal and his sole purpose was to prioritize aesthetic and historical intrigue, portraying Middle Eastern societies primarily as historical curiosities or romanticized backdrops, a realm in which he was somewhat familiar with. However, I believe this absence of this important representation significantly contributed to Western misconceptions about Middle Eastern cultures, painting them as static, passive, and timelessly exotic. Since the people of the Middle East weren’t represented in a positive and headlining light, this allowed a skewed perception to foster and allowed for the understanding of foreign cultures to be ignored and it authorized Europeans to deny and reject the evolving and dynamic nature of these societies. Additionally, by reducing individuals to picturesque elements, Roberts stripped locals of their individuality and agency, thereby reinforcing harmful stereotypes and prejudices. By presenting these beautiful yet superficial images of what seemed to be of Middle Eastern life, Roberts shamelessly contributed to the colonial narratives that portrayed Eastern societies as culturally inferior, static, and ripe for Western intervention and domination. Roberts’ work thus exemplifies how Orientalist portrayals perpetuate cultural misunderstandings and stereotypes, reinforcing Western imperialism’s ideological underpinnings. While visually compelling, his artistic legacy underscores the critical need to contextualize Orientalist art within its broader colonial and cultural frameworks.

Colonial Gaze and Power Dynamics

Orientalist art represents an inherent power imbalance, whether the artist is aware or not. This is instantly created because Western artists held the authority to represent Eastern cultures without authentic engagement or accountability to the locals depicted. Without the subject holding the artists accountable, there is a never ending cycle of misrepresentation. David Roberts’ paintings specifically exemplify this imbalance by when he decided to share Western ideals and fantasies to the European public instead of expressing the authentic local experiences. It was rare for his depictions to share the entire true Middle Eastern experience, as he was very distinct when it came to displaying Western superiority and reinforcing imperialist ideologies, which was extremely harmful to any community that was victim to colonial ambitions and cultural domination. In works such as “View of Cairo,” Roberts expertly positions the gaze of Western viewers at a vantage point above the city. This was an intentional and symbolic choice in order to place them in a position of dominance and observation. Compositional choices like this were used so frequently, and they mirror colonial power dynamics. In all honesty, even if he wanted to, Roberts’ visual narratives rarely allowed space for local voices or interpretations. His paintings were constructed for Western consumption. He in some ways had to filter Eastern societies through a lens that would be palatable to Western values. By only allowing the repeated portrayal of locals as passive observers in their own society reinforced simply just contributed to intellectual superiority. Using these strategies allowed for Roberts to sustain colonial hierarchies and justified European colonial interventions as civilizing missions, perpetuating the problematic idea that Eastern societies required Western oversight and guidance. Roberts’ representation of Eastern people and societies were only situated through Western perceptions, reflecting broader colonial attitudes that positioned the West as culturally advanced and rational, while the East was depicted as backward and irrational. His paintings did not have the ability to remain neutral but instead as we keep seeing as a theme in his works, reinforced power structures by visually asserting the presumed superiority and rational authority of Western perspectives, thereby subtly legitimizing colonial exploitation. Roberts’ representations embodied a Western-centric perspective, perpetuating a sense of authority and entitlement to depict Eastern cultures without authentic engagement or local accountability. His prints likely contributed to the “cultural conditioning” favorable to British imperialism by presenting Arabs as generalized stereotypes rather than as fully realized human beings.

Exoticizing the East

David Roberts’ paintings frequently highlighted exoticized portrayals of the Middle East, reflecting his fascination with picturesque ruins, grand architectural sites, and local peoples. These depictions contributed significantly to shaping Western narratives of Eastern cultures, often reinforcing a sense of cultural stagnation and timelessness. Roberts’ artistic choices were deliberate, focusing primarily on scenes that evoked wonder and curiosity among European viewers, thereby feeding into stereotypes that portrayed the Middle East as an unchanging and static civilization. Roberts’ works consistently depicted notable landmarks such as mosques, bustling bazaars filled with vibrant colors and exotic goods, and vast desert landscapes, all rendered with meticulous detail and dramatic lighting effects. These scenes, while visually stunning, reinforced Western perceptions of the East as an exotic “other”—an alien and mysterious world disconnected from modern progress. His repeated focus on ruins and ancient structures subtly implied a narrative of decline, suggesting that the cultures he depicted were relics of the past rather than vibrant societies with contemporary relevance. Roberts’ depictions of bazaars, for instance, were particularly influential in exoticizing the East. His scenes captured crowded marketplaces brimming with merchants and buyers, vibrant fabrics, exotic spices, and animals—scenes distinctly removed from the everyday experience of his European audience. Through his selective portrayal, Roberts reinforced notions of the East as alluring yet distant and unknowable, subtly affirming Western curiosity and superiority.

Legacy and Impact

The impact and legacy of David Roberts’ paintings and lithographs remain complex and multifaceted. In simple terms, yes his works were extremely well done and there’s no denying that Roberts had immense talent when it came to working on landscapes, but when you dig deep and really analyze the context behind his work and what he had to do to achieve, you understand why his works need to be heavily critiqued as well. Due to his popularity, his works were able to significantly shape European perceptions of the Middle East during the 19th century. In doing so, his paintings were able to establish lasting visual tropes and stereotypes that continue to influence contemporary understandings of the region. So while Roberts’ was responsible for providing an ultimately inaccurate depiction of the Middle East, he was also able to provide one of the earliest extensive visual documentations of the Middle East. He helped create and bestowed profoundly European fascination and curiosity about the region, in both positive and negative ways. Artists like Roberts, nonetheless, influenced subsequent generations of artists, travelers, and writers who perpetuated similar representations of the East. Contemporary scholarship now highlights the importance of analyzing Roberts’ legacy within the broader context of colonial power relations, recognizing both the artistic value and the ideological implications of his works.