Gendered Access and Women’s Travel Narratives in 19th Century Egypt

Lord Cromer, alongside many other men, was among the first people to explore Egypt. Like most studies, men were financially, socially, and religiously allowed and capable of exploration and scholarship. Women, on the other hand, were not involved in studies of Egypt until later on in the century. When they were involved in traveling through Egypt, they were there alongside their husbands, cooking and cleaning. Their main role was the feminine support of their male superiors. Despite these barriers, women later on in the century fought their way into exploration, archaeology, and science. This website is a study on the importance of these women’s accounts of Egypt and an exploration of three such women’s lives and studies.

Historical Background: It is important to consider the context in which these women were traveling and the culture in which they were recording their experiences. The nineteenth century witnessed a surge in British interest in Egypt, driven by imperial ambitions and an increase in romanticized Orientalism. While male travelers like Edward Lane, Richard Burton, and Lord Cromer approached Egypt as either a field of study or a subject of colonial reform (all things based within the realm of politics and imperialism), women entered the scene with different tools: the journal and the letter. Their work was often dismissed as sentimental or overly personal, as was much of female literature and scholarship of the time, and yet it is precisely this intimacy and personality that allowed them to observe what men were not able to. Domestic spaces, emotional relationships, and caregiving were all domains that their male peers overlooked and dismissed. These spaces, conversely, say the most about culture and tradition, as arguably, tradition is built around the family. This is what Egypt’s female explorers got a close look at. It is within this context that Amelia B. Edwards, Lucy Duff Gordon, and Florence Nightingale began to craft narratives that combined observation with introspection. These women also challenged imperial authority in their own way and were not entirely separate from the political sphere that their male counterparts inhabited. They merely experienced both worlds: domestic and social, while navigating their own position as Western women abroad.

Where did female travelers go?

All different places!! Some went on archeological trips down the Nile, like the strong-willed Amelia B. Edwards. Others traveled smaller distances, going into communities like Florence Nightingale. More women took up residence in Egyptian cities, like Luxor, such as Lady Lucie Duff Gordon.

Female Travelers: What makes them different?

One of the defining features of these women’s writings is their access to private and domestic spaces that were often closed to male travelers. In Islamic and traditional Egyptian households, men were often barred from entering areas such as the harem or women’s quarters. Therefore, men were never given the chance to study how culture and tradition played out in these spaces and touched members of the inner family or the greater community. However, as women, Edwards, Gordon, and Nightingale were accepted and welcomed into these settings. These domestic spheres held tremendous cultural significance, serving as spaces where traditions were practiced, knowledge was transmitted, children were educated, and social hierarchies were reinforced or resisted.

Cultural Assimilation?

What sets these women apart is not just their access, but also their attitudes. Unlike male explorers who often approached Egypt as a land to be conquered and exploited, Edwards, Gordon, and Nightingale each wrote with empathy and admiration. Their gendered experiences cultivated a more reciprocal form of cultural exchange, in which their own values were challenged as much as confirmed. Gordon’s deep affection for her Egyptian friends, Nightingale’s concern for local health, and Edwards’s dedication to preservation each suggest a model of engagement based on respect rather than superiority. Instead of approaching their exploration and study of Egyptian culture from an Oriental and deeply imperial perspective, they approached Egyptian history in a woman-to-woman way. They saw Egyptian women as like them instead of creatures or animals to be mocked and picked apart. This empathy and intimacy make their accounts of their time in Egypt powerful, simply because they wrote of Egypt as it had never been written about before.

Women had uniquely gendered access to private and domestic spaces, and they provided perspectives on Egyptian culture that are vastly different from the more oriental, imperialist, male-authored narratives of the time.

Amelia B. Edwards:

Amelia B. Edwards began her career as a novelist and journalist, but it was her journey to Egypt in the 1870s that redefined her legacy. Her background in writing was groundbreaking, but she didn’t stop there. Her growing fascination with archaeology culminated in her founding of the Egypt Exploration Fund, aimed at preserving and documenting Egyptian antiquities for scholarly and public knowledge. This extensive background in literature gave her travel writing an expressive, vivid quality, making ancient Egypt accessible and enchanting to British readers. Edwards was not only among the first women to write extensively on Egyptian monuments, but she also illustrated her own books, adding further depth to her work.

Lady Lucy Duff Gordon:

Lucy Duff Gordon’s time in Egypt was prompted not by intellectual curiosity but by necessity. Gordon was suffering from tuberculosis, and she traveled to Egypt in search of a more hospitable climate. This led her to end up living in Luxor for several years. From her home there, she wrote a series of letters to family and friends that would later be published as Letters from Egypt. Gordon immersed herself in the local culture, building genuine relationships with her Egyptian neighbors and embracing daily life in a way few Westerners did. Her curiosity and open-mindedness made uniquely Egyptian spaces available to her in a way that few people (male or female) had ever experienced. In short, Gordon became a local. Her perspective was strikingly critical of British imperialism and sympathetic to the Egyptian way of life, which was a rare and bold stance at the time.

Florence Nightingale:

Though best known for her revolutionary work in modern nursing, Florence Nightingale also spent formative time in Egypt in the early 1850s. Her letters from this period focus on social conditions, health practices, and the lives of women. In contrast to Edwards’ archaeological insights or Gordon’s social commentaries, Nightingale offers mostly observations on the medical sphere of Egyptian life, a sphere men had long overlooked in their romantic Orientalist tendencies. Traveling before her pivotal service in the Crimean War, Nightingale’s observations reflect a growing humanitarian impulse that would later define her career and legacy. While her travel writing was not focused on archaeology or ethnography, her medical training and moral focus offer valuable commentary on Egyptian domestic life, particularly in relation to women’s health and caregiving structures.

“In these and in a hundred other instances, all of which came under my personal observation and have their place in the following pages, it seemed to me that any obscurity which yet hangs over the problem of life and thought in ancient Egypt originates most probably with ourselves. Our own habits of life and thought are so complex that they shut us off from the simplicity of that early world.”

Amelia B. Edwards

Amelia B. Edwards and A Thousand Miles Up the Nile:

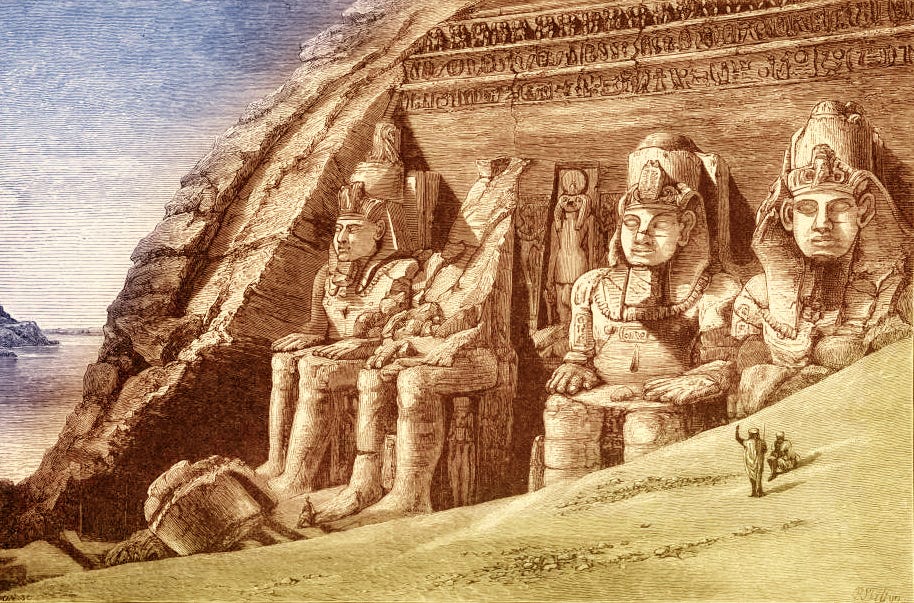

Amelia B. Edwards’ 1877 book, A Thousand Miles Up the Nile, blends lyrical travelogue with serious archaeological documentation. It was rare at the time to see a woman commenting on archeological artifacts and sites. Edwards’s sketches and descriptions of ruins such as Abu Simbel not only captivated readers but also called attention to the degradation of these ancient structures through looting and neglect. At a time when Egyptology was still finding academic footing in Britain, Edwards advocated for the scholarly preservation of antiquities, and her efforts eventually contributed to the integration of Egyptology into the curriculum at University College London.

Lady Lucie Duff Gordon and her Letters From Egypt:

Because of her long-term residence and integration into the community, Gordon’s insights were intimate and grounded in mutual respect rather than academic distance. There was no separation or boundary between her and the people she was surrounded by. She also did not approach her writings as case studies, but merely her personal writings about the people she interacted with on a daily basis. In contrast to male travelers who often relied on interpreters or mediated contact, Gordon’s letters reveal her gradual acquisition of Arabic and her openness to learning from the people around her. She celebrated festivals with her neighbors, adopted local customs, and even described herself as a participant rather than an observer.

Gordon’s writings are notable for their nuanced portrayals of Egyptian domestic life. She describes visiting homes, observing weddings, and discussing politics with Egyptian women. These are all activities from which male travelers were almost always excluded, due to strict religious and cultural norms. Her critiques of European arrogance and cultural superiority come not from ideology but from her daily experience of colonial injustice. She lived the daily life (mostly) of an Egyptian woman. She writes with deep affection for her neighbors and indignation toward the interference of British officials who failed to understand or respect the communities they ruled. This makes her letters feel personal, heartwarming, and powerful, as a British woman writes against Britain and opens her own heart and mind to the culture that is surrounding and healing her.

Florence Nightingale and her Letters From Egypt:

Nightingale’s journals and correspondence from Egypt document her observations of local hospitals, birthing practices, sanitation systems, and the status of midwives. Unlike her male peers, who often generalized Egyptian society through an Orientalist lens, Nightingale was methodical and precise, recording the inadequacies she observed with a reformist mindset. She came to her time in Egypt not only with the goal of recording, but with the goal of change. She noted the high infant mortality rates, the lack of proper medical care for women, and the role of superstition in healthcare practices.

What stands out in Nightingale’s writing is not just her concern for health outcomes, but her acknowledgment of systemic inequality. She traced many of the issues she observed to the failures of colonial administration and the marginalization of women. These are insights that would influence her later policy recommendations in Britain and India. Her experience in Egypt planted the seeds of an internationalist, gender-conscious humanitarianism that would define her public work.

Female Travelers and the Tone of Scholarship

The tone of their writing frequently diverges from that of male contemporaries like Richard Burton or Lord Cromer, whose accounts are often laced with judgment, exoticism, and overt political justification. While male narratives prioritized conquest or the consolidation of empire, these women offered reflections on intimacy, emotional complexity, and everyday life. This difference is not incidental – it reflects the social roles they inhabited and the moral frameworks they brought with them. Male explorers reflect the political state they came carrying, whereas female explorers were in Egypt to study, heal, and form waves of change.

Amelia B. Edwards, Lucy Duff Gordon, and Florence Nightingale each brought a distinctive voice and unique perspective to the collection of nineteenth-century travel writing about Egypt. With their gendered access to domestic and private spheres, they expanded the Western understanding of Egyptian life far beyond the temples and tombs that fascinated their male counterparts. They wrote of the root of culture: the home. Whether advocating for archaeological preservation, documenting intimate domestic environments and customs, or analyzing health systems and taking part in medical procedures, these women offered accounts rich in humanity, intimacy, and cultural nuance. In contrast to the dominant male narratives of the time, which were often steeped in Orientalist assumptions, the writings of Edwards, Gordon, and Nightingale continue to remind us of the value of diverse perspectives in historical scholarship. Their work continues to speak to the power of empathy and curiosity in bridging the gap between cultures.

Conclusion:

Amelia B. Edwards, Lucy Duff Gordon, and Florence Nightingale each brought a distinctive voice and unique perspective to the collection of nineteenth-century travel writing about Egypt. With their gendered access to domestic and private spheres, they expanded the Western understanding of Egyptian life far beyond the temples and tombs that fascinated their male counterparts. They wrote of the root of culture: the home. Whether advocating for archaeological preservation, documenting intimate domestic environments and customs, or analyzing health systems and taking part in medical procedures, these women offered accounts rich in humanity, intimacy, and cultural nuance. In contrast to the dominant male narratives of the time, which were often steeped in Orientalist assumptions, the writings of Edwards, Gordon, and Nightingale continue to remind us of the value of diverse perspectives in historical scholarship. Their work continues to speak to the power of empathy and curiosity in bridging the gap between cultures.

Suggested Reading on This Topic:

Cherif, Lobna. “Extreme Virtue and Horrible Vice: Sir Richard F. Burton and Orientalism.” Academia.edu.

Duff Gordon, Lucy. Letters from Egypt. Edited by Janet Ross. London: R. Brimley Johnson, 1902. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17816/17816-h/17816-h.htm.

Edwards, Amelia B. A Thousand Miles Up the Nile. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1877.

“The Buried Cities of Ancient Egypt.” In Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers, 37–69. Cambridge Library Collection – Egyptology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

“The Explorer in Egypt.” In Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers, 3–36. Cambridge Library Collection – Egyptology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

“The Literature and Religion of Ancient Egypt.” In Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers, 193–233. Cambridge Library Collection – Egyptology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Nightingale, Florence. Letters from Egypt. London: Printed by A. & G. A. Spottiswoode, 1854. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (accessed April 21, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CZZLTE326893089/NCCO?u=nclivedc&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=3768c408&pg=320.

Tucker, Judith E. “Traveling with the Ladies: Women’s Travel Literature from the Nineteenth Century Middle East.” Journal of Women’s History 2, no. 1 (March 1, 1990): 245–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2010.0167.

Winslow, William Copley. The Queen of Egyptology (Amelia B. Edwards …). [Chicago?], 1892. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89097318018.