Collecting Egypt: The British Museum, the Louvre, and the MET

Collecting Egypt

One way in which Egyptomania is embodied is through expansive Egyptian collections in Western museums and institutions, which attract millions of visitors every year. This form of Egyptomania seen today really begins in 1922 with the discovery of King Tutamnkhamun’s tomb. This was preceded by 100 years of Western investigation into ancient Egypt, beginning with the French in the early 1800s, when the acquisition of Egyptian antiquities began in earnest. From the mid-19th century on, Western institutions actively engaged in the plundering and importation of ancient Egyptian antiquities. With political tension between multiple European colonial powers, competition to attain the spoils of empire led to a collecting frenzy in the centers of the ancient world, with major attention on the antiquities of ancient Egypt. With this century of collectionism, numerous Western institutions obtained expansive amounts of antiquities, largely through colonial activities. These colonial-obtained assemblages now form the bulk of Egyptian collections in major world museums, including the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The ownership of these collections by major Western museums shows the legacy of colonialism and continuing imperialist positions that impact the heritage of peoples around the world today.

Past

Beginning of Antiquities Acquisition

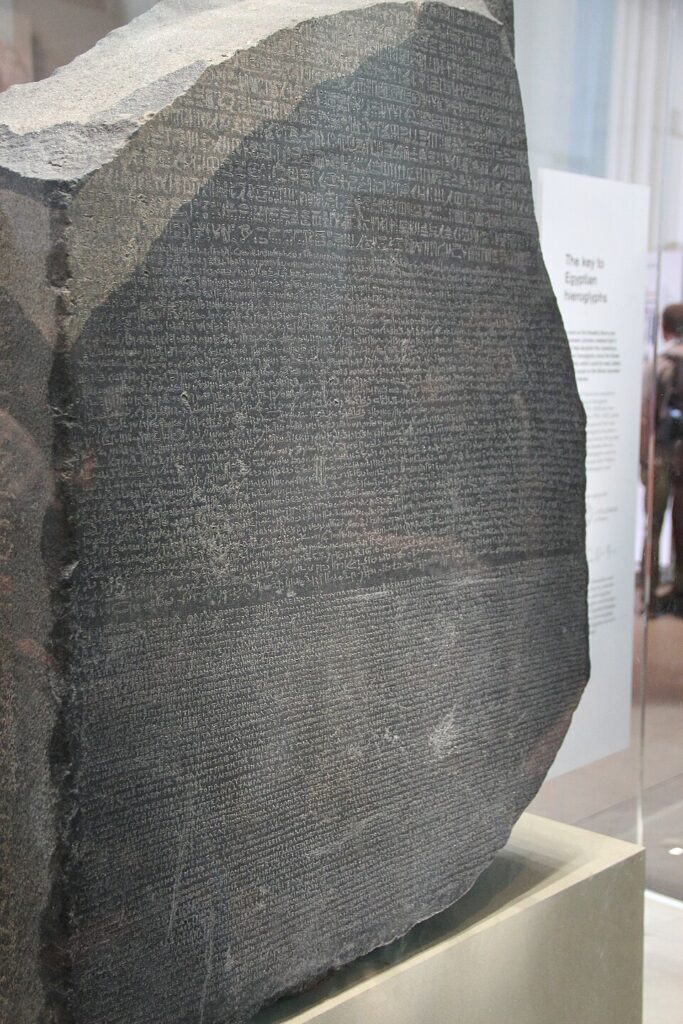

In 1798, Napoleon launched the French campaign into Egypt to take control of the territory and its advantageous trade routes. Napoleon also had an interest in documenting French discoveries in Egypt, and so the French forces included scholars and scientists, who were responsible for making detailed accounts of Egypt. Upon his arrival, Napoleon founded the Institute of Egypt to aid in the study of Egyptian history, art, and sciences. Any artifacts or objects of interest found during the military’s advancement were sent here before eventually going to France and the newly founded Louvre (1793). Although Napoleon’s forces were defeated by joint British and Ottoman forces in 1801, France was allowed to import its acquired antiquities, except for the Rosetta Stone, which was claimed by British forces and sent to the British Museum (1802), where it remains today.

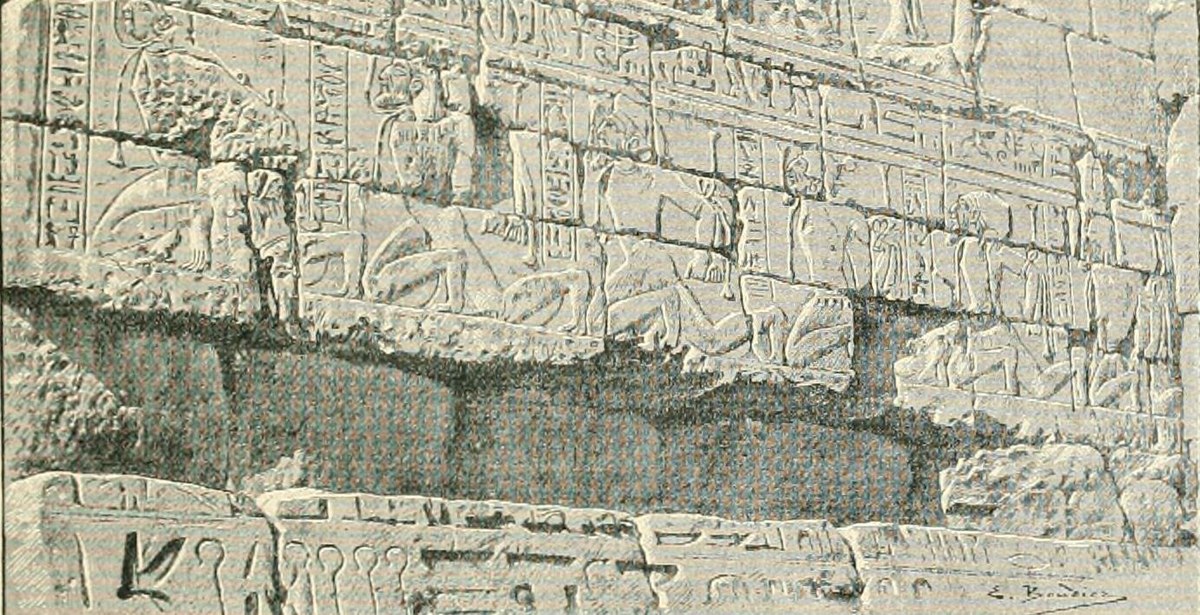

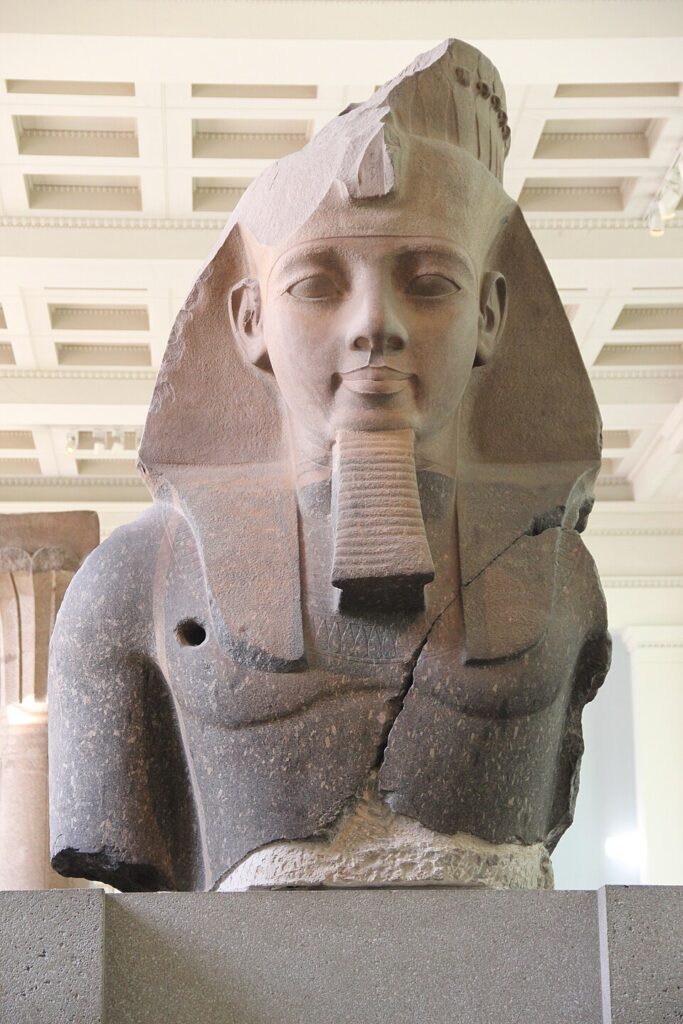

Following the Napoleonic wars, interest in ancient Egypt started to grow among Western countries, leading to increasing investigation into ancient monuments and antiquities by European antiquarians and collectors. Britain soon got involved due to their rivalry with France, sending their own acquisition agents into the field. In 1819, excavator and archaeologist Giovanni Belzoni acquired an enormous stone bust—the “Younger Memnon,” a statue of Ramses II— at the behest of the British Museum. This was then displayed in the original museum’s Egyptian Sculpture room and is still displayed in the museum today. The next year, in 1820, French collector Sebastien Louis Saulnier used gunpowder to extract the enormous Zodiac relief from the ceiling of the Temple of Dendereh, causing considerable damage to the structure in the process, which was then sent to the Louvre.

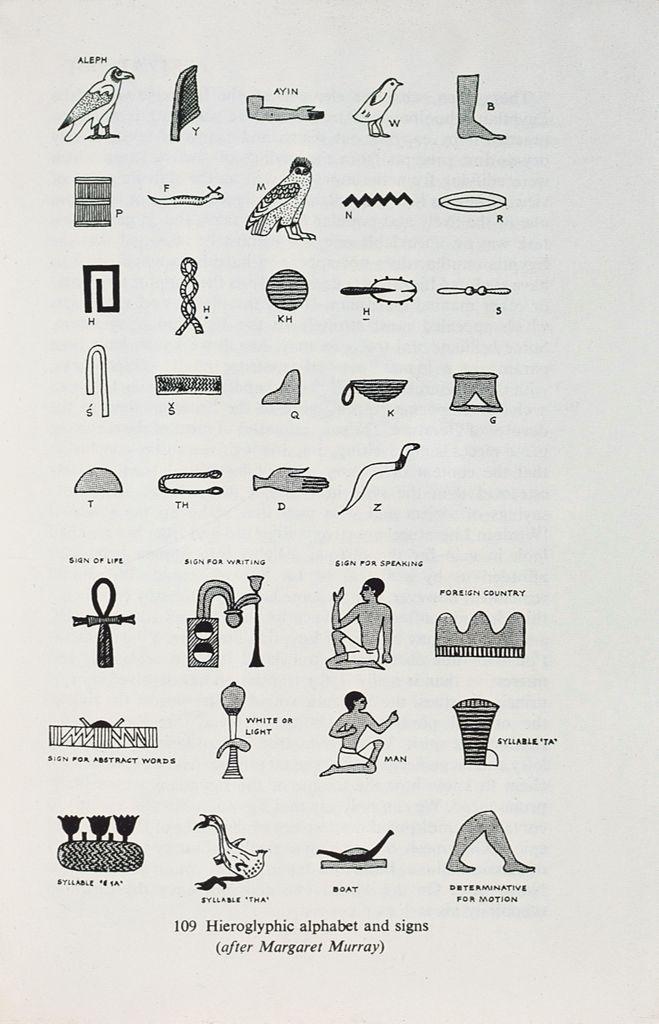

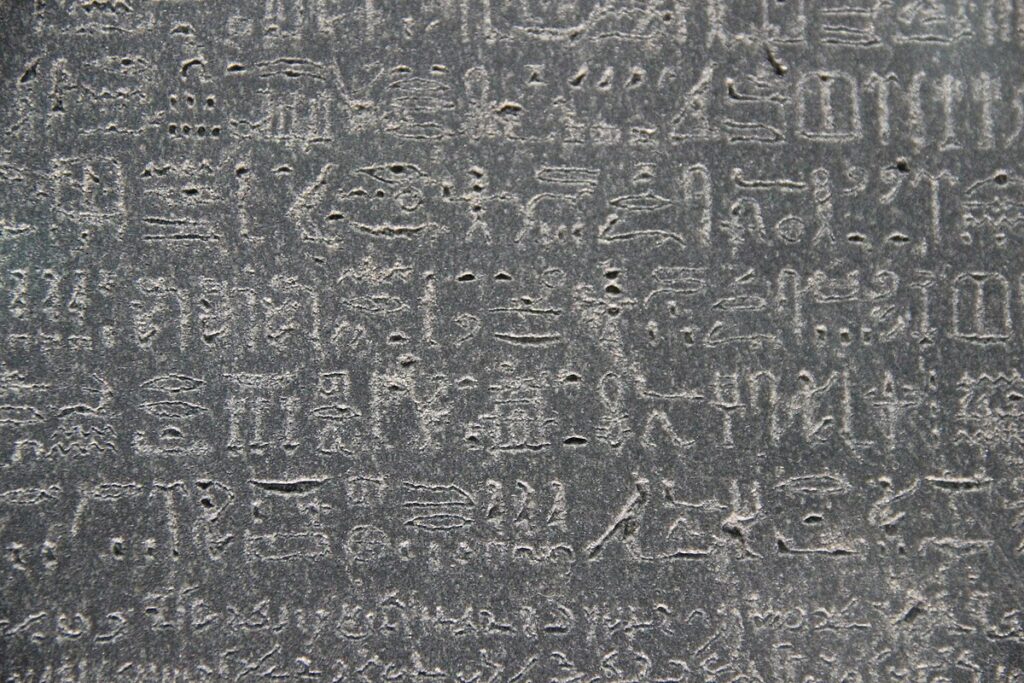

At this time, European museums, curators, and art historians considered ancient Egyptian antiquities not as items of fine art but instead as primitive curiosities that didn’t fit the standards of ancient Greek and Roman art. As ancient Egypt lacked a readable written history, it was not considered a legitimate civilization in the eyes of European historians and art curators. This soon changed, however, with the decipherment of hieroglyphs.

In 1822, French scholar Jean-François Champollion deciphered the basics of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone. With the decipherment of hieroglyphs, the field of Egyptology began in earnest, as Egypt now had a rich ancient history that could be read and studied. From this point on, ancient Egypt was accepted as one of the great civilizations of the ancient world and a powerful center of early civilization. The image and value of Egyptian antiquities were elevated, and they were now viewed as fine art and the works of a great civilization. With its increasing value, Germany, Italy, and America eventually joined the race for Egyptian antiquities in the late 1800s, getting involved in fieldwork to obtain items for their countries’ collections.

Imperialism and Colonialism

In the 1800s, the collecting of antiquities and material culture became a tool of colonialism and a symbol of the influence imperial countries had over other peoples. To promote their achievements and “discoveries,” Western powers built museums to showcase their findings, some of which were located in Egypt. One such museum was the Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo, which opened under British oversight in the 1800s with the intent of catering to European audiences. Most museums and collections established in the 19th century were tied to colonialism, imperialism, or missionaries in some way and served an important role in promoting and reinforcing imperialist narratives. Central to the collection imperative were the Doctrine of Discovery, Orientalism, and universalism.

The Doctrine of Discovery was a historical legal concept and racist doctrine that considered anything Europeans found in foreign or non-White territories to be “discovered” by them and thus rightfully theirs to claim. This served to justify the exploitation of resources and the people they conquered, including the theft of objects and artifacts of cultural heritage. This contributed to the rise of Orientalism as the West became increasingly introduced to areas of North Africa, the Middle East, and what was generally referred to as the “Orient.” A central aspect of Orientalism is the appropriation, romanticization, and exotification of the peoples and cultures of the “Orient,” especially in how they are depicted in art, literature, and other forms of media. The expanding interest and influence over Egypt in the 1800s was directly tied to the rise of Orientalism, and ancient Egypt was portrayed in media and museums according to Orientalist expectations of Western audiences.

Despite the evident power and wealth of ancient Egypt, it was distanced from the civilization of the West as an inferior and failed empire of the past. Western imperial powers used this collapse to showcase their superior prowess and success in the Enlightenment narrative. This portrayal was useful in the universalist narrative, which argued that both the failed great ancient civilizations and the modern Western empires shared a common past and evolutionary trajectory, promoting European exceptionalism and supremacy. Ancient Egypt became a casualty on the pathway to civilization, which it never quite attained. This unique status made it an optimal target for its appropriation and use in supporting the colonial narratives in museums. In this narrative, the tragic yet glorious past of ancient Egypt was contrasted with the lifestyle and culture of contemporary Egyptians, who were seen as inferior and unworthy of this great heritage. With the argument that ancient Egyptian antiquities were in danger of neglect or damage under Ottoman rule and the seeming indifference of contemporary Egyptians in the 1800s, Western institutions claimed that these antiquities were better off in the hands of European nations, who could better protect, preserve, and appreciate these objects. This stance is still promoted by institutions today.

Discovery of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb

By the early 1900s, more and more institutions were pursuing archaeological projects in Egypt, eager to claim artifacts for their own collections. This included U.S. institutions, including Harvard University in 1905 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1906. Underlying this growing international interest were intentions of establishing imperial power and strengthening nationalism through institutions. Museums also shifted from being mainly curio cabinets and places for displaying antiquities, to institutions with more complex roles: becoming centers of learning as well as manifestations of colonial politics.

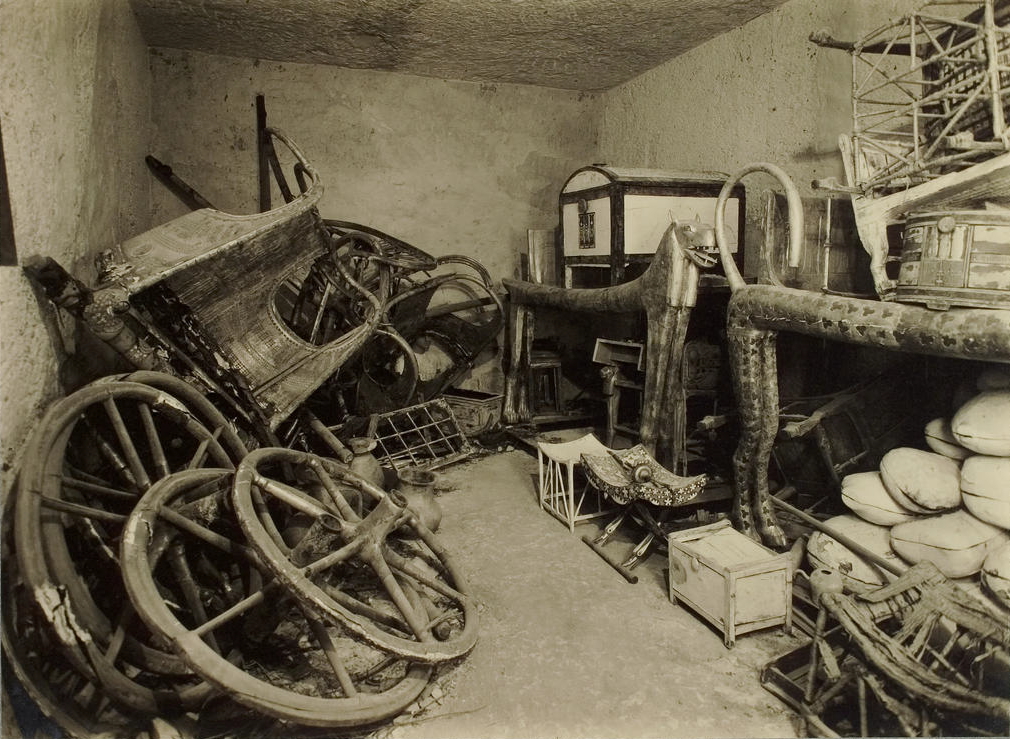

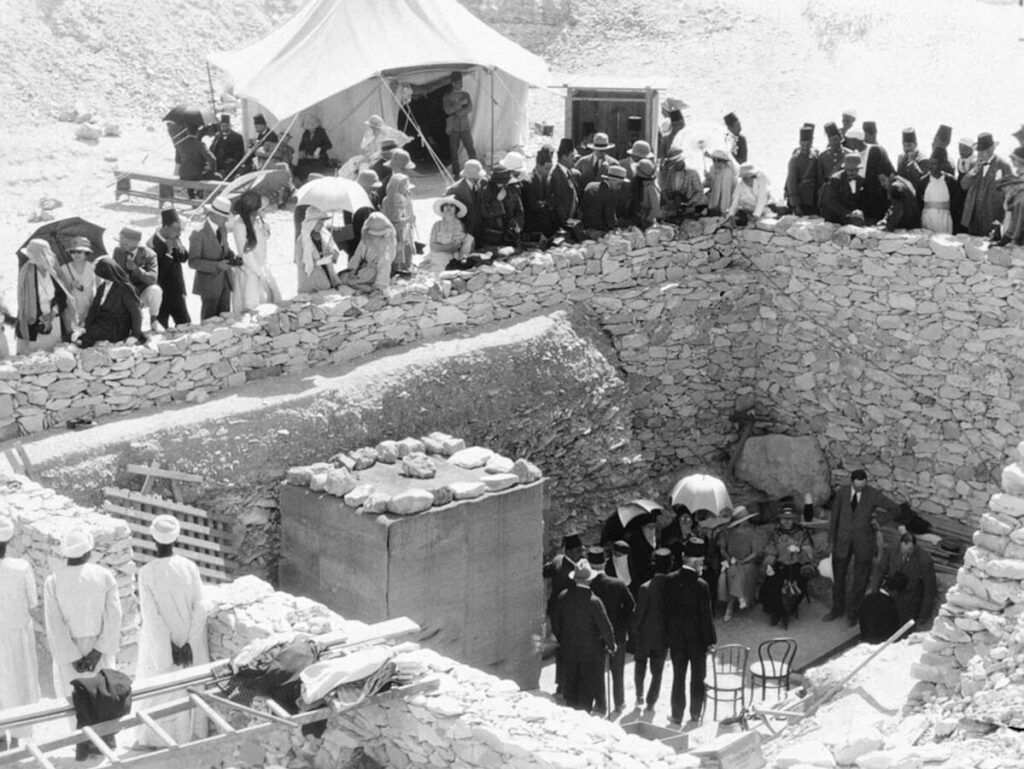

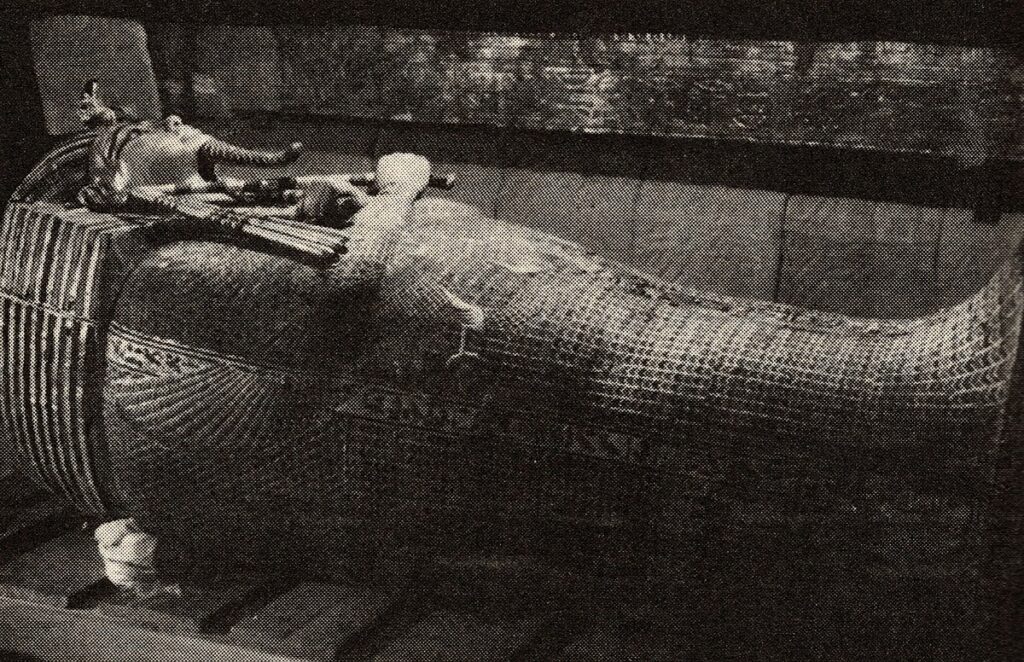

Egyptology took a major turn in 1922 with the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by British archaeologist Howard Carter. This event sparked international interest and fascination with ancient Egypt, creating a more intense wave of Egyptomania than ever before and forming the basis of modern Egyptomania. Tutankhamun’s tomb is still the most complete pharaonic tomb ever discovered, with only the most exterior chamber having signs of looting in antiquity. This discovery renewed the fascination with ancient Egypt through the unprecedented majesty of the wealth, artifacts, and art found inside. This discovery also marked a change in the local politics concerning Egyptian antiquities and heritage.

While there had been prior attempts to limit the looting and export of antiquities from Egypt by Ottoman officials, these laws were largely unsuccessful, with antiquities-acquisition agents either finding loopholes or ignoring these rarely enforced laws completely. In 1922, Egypt received formal independence from British rule and became a sovereign nation. King Tut’s tomb was of such unprecedented monetary, cultural, and historical value that the new Egyptian government quickly became involved. With the new government, politicians in Egypt were eager to use Egyptian history—and King Tut in particular—as emblems of the nation: King Tut became a symbol of national independence. With the instrumental political and cultural value of the Egyptian past, the Egyptian government would no longer be complicit in the taking of its antiquities by Western institutions, and the Department of Antiquities revised the laws. From then on, Egypt claimed ownership of all excavated artifacts with no obligation to split the finds with involved Western institutions. Thanks to this change, the artifacts and collection of Tutankhamun’s burial treasures were kept in Egyptian possession and prevented from being scattered to institutions around the world.

Present

Modern Collections: Major Museums

The British Museum, the Louvre, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art are three of the largest museums in the world, each possessing large Egyptian collections. The British Museum, in particular, houses the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities outside of Egypt. Each of these museums is located in a major world city (London, Paris, and New York), reflecting the lasting political, cultural, and economic power of these countries and institutions and the continuing legacies of colonialism.

Founded during the French Revolution in 1793, the Louvre aimed to collect and display the treasures of the nation; this expanded to include its colonial spoils. France was the first of the Western imperial powers to start collecting Egyptian antiquities, and opened the first Egyptian museum in the Louvre in 1827. Today, the Louvre has four galleries of Egyptian antiquities; of these, the most famous items include the Dendera Zodiac, the Great Sphinx of Tanis, and the reconstructed Mastaba “chapel” of Akhethotep.

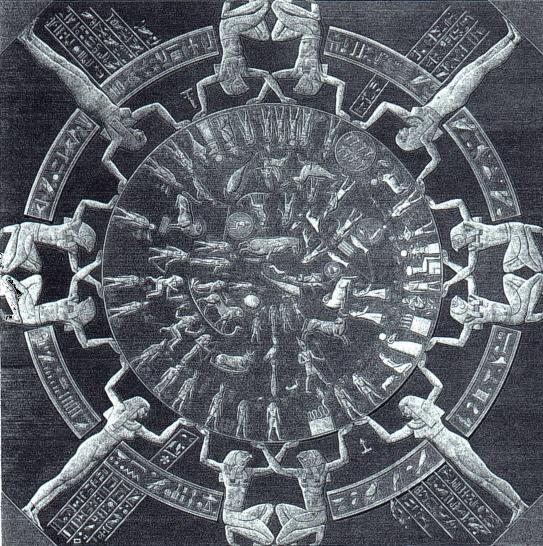

The Dendera Zodiac

The first of the Egyptian antiquities that the Louvre obtained. It is an enormous stone ceiling relief featuring the constellations of the zodiac. It was originally part of the ceiling of the Hathor Temple in Dendera until 1820, when French collector Sebastien Louis Saulnier used gunpowder to remove it, after which it was sent to the Louvre.

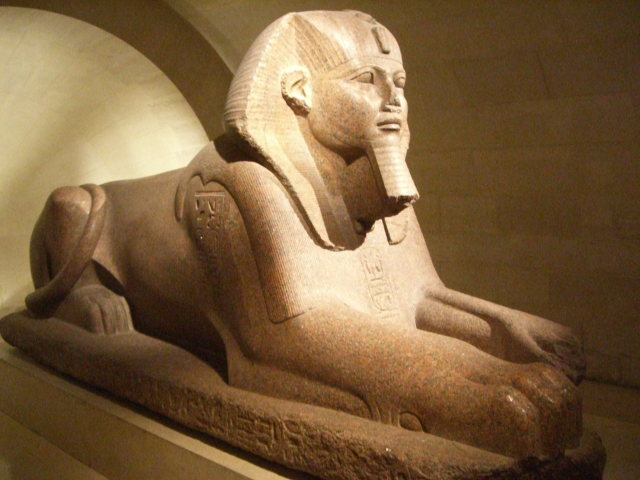

The Sphinx of Tanis is one of the most recognizable large statues in the Louvre, carved from pink granite. It is so iconic that it is featured in a page-width image at the top of the Louvre’s webpage on the Egyptian Art gallery. The Sphinx was found in the ruins of a temple to Amun-Ra in the ancient capital of Tanis before being purchased by the Louvre. Today it sits imposingly at the entrance of the underground Department of Egyptian Antiquities—dramatically named The Crypt of the Sphinx—where it serves as the “Guardian of Egyptian Art.”

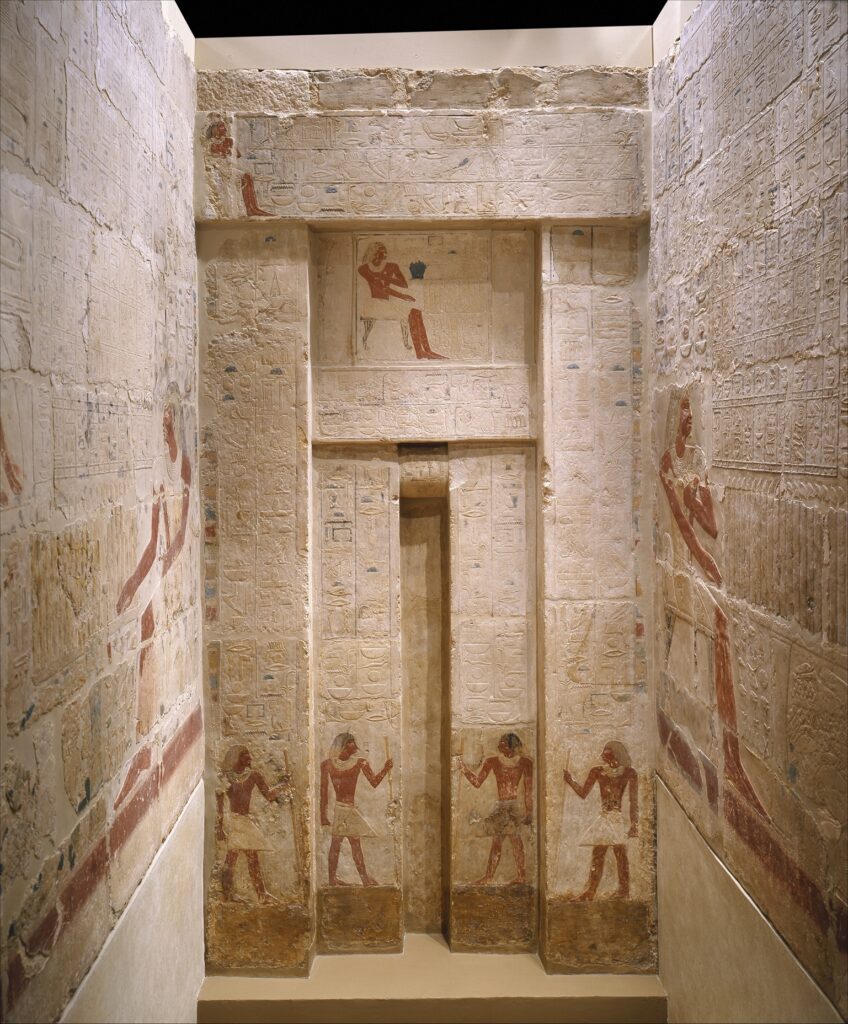

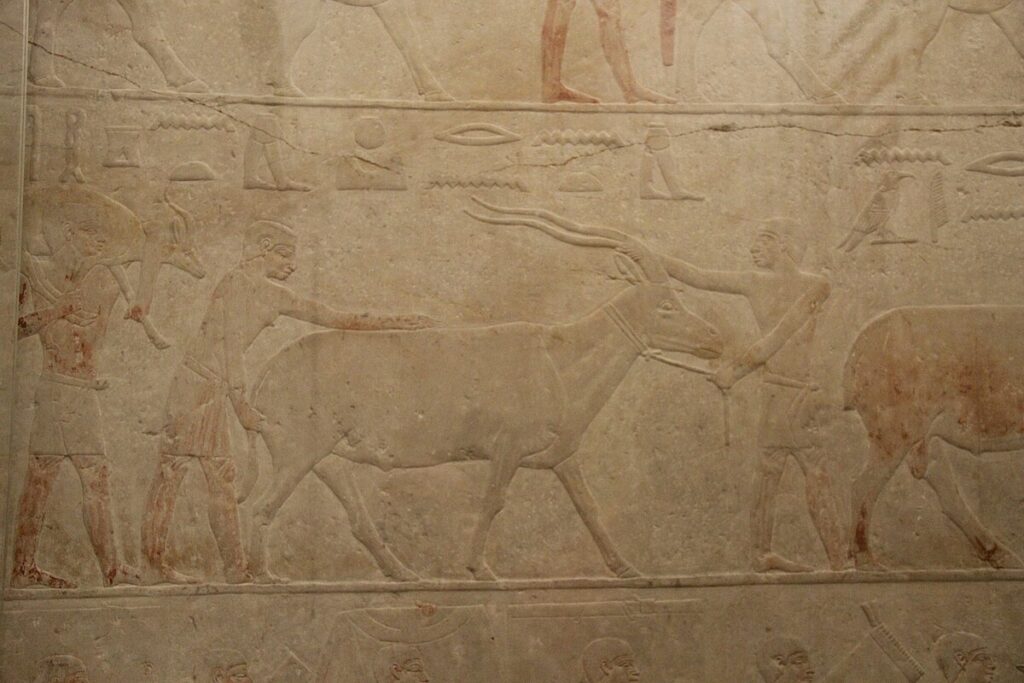

The Mastaba of Akhethotep

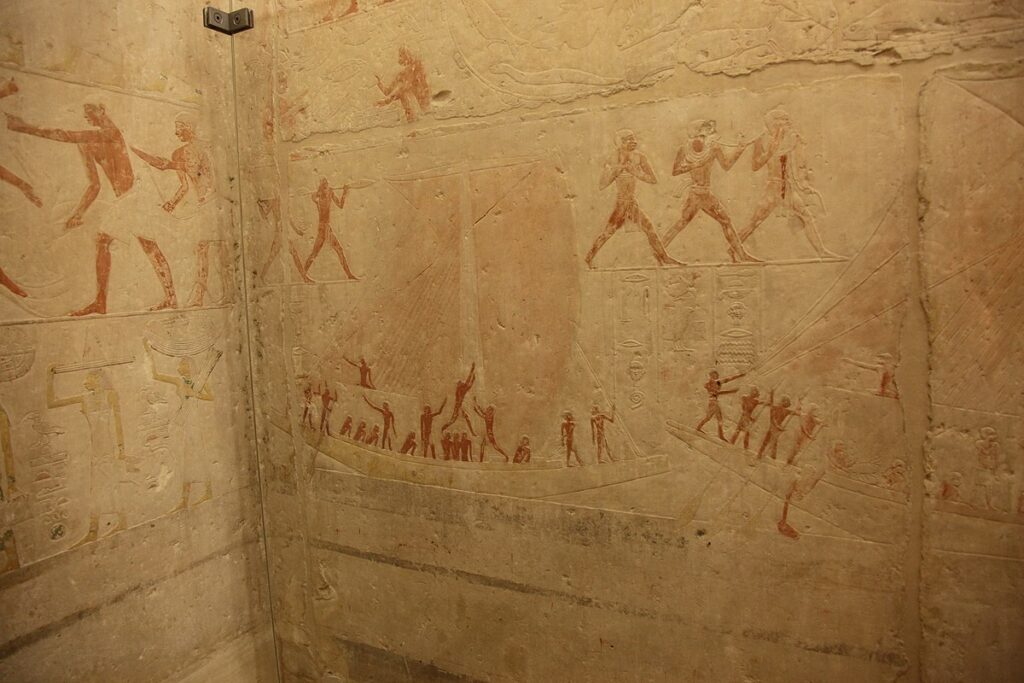

Mastabas were a part of Old Kingdom tombs that royalty and those within the pharaoh’s inner circle were entitled to be buried beneath. They might be called a sort of chapel or funerary monument, as it was a large structure positioned over the subterranean path to the burial chamber. It was inside this chapel-like chamber that offerings could be left for the deceased. In 1903, the Louvre purchased this mastaba from the Egyptian government and reconstructed it within the museum piece by piece. The walls of the mastaba feature painted carvings with hieroglyphic inscriptions depicting scenes of daily life, plants, animals, and scenes from Akhenthotep’s own life.

The British Museum

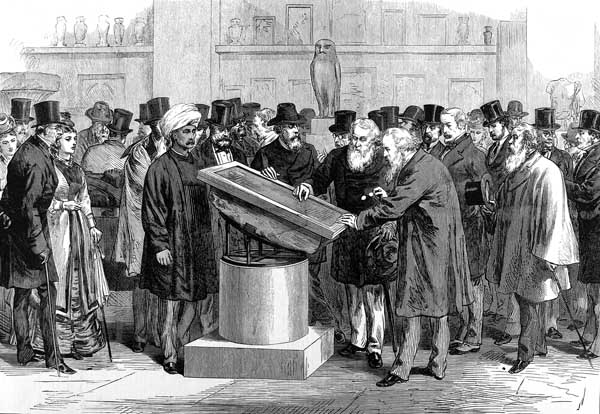

The British Museum was founded in London in 1753 and was one of the world’s first public and state museums. Today, it holds the largest collection of Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt. As Britain expanded its colonial influence through the 19th century, the museum became a symbol of the empire and its colonial achievements. It also served as an “imperial archive,” holding the most valuable and impressive objects and material culture acquired by the empire, symbolically making London the heart and center of the empire. Even today, the British Museum identifies itself as a “universal collection” and “universal museum” housing material culture and antiquities from around the world.

Today, the British Museum has five galleries featuring Egyptian artifacts going back to 11000 BCE. Highlights of this collection include artifacts such as wall paintings; funerary objects, coffins, and sarcophagi; statues and statuettes of animals, people, and gods; pottery; stone palettes; jewelry; religious objects; and numerous human and non-human mummies. The British Museum has 184 partial or complete human mummies, the largest collection of Egyptian mummies outside of Egypt. Of all the museum’s Egyptian artifacts, by far the most famous is the Rosetta Stone.

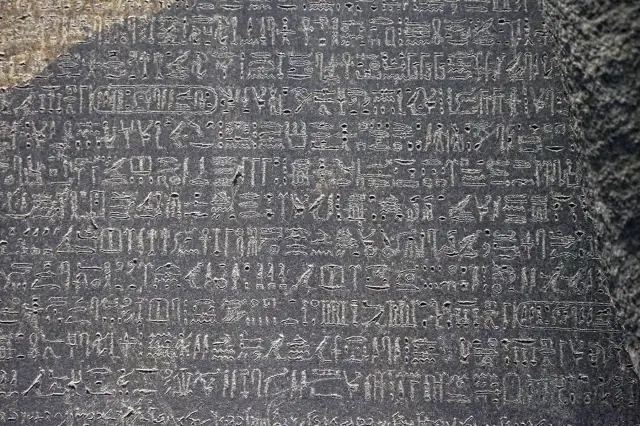

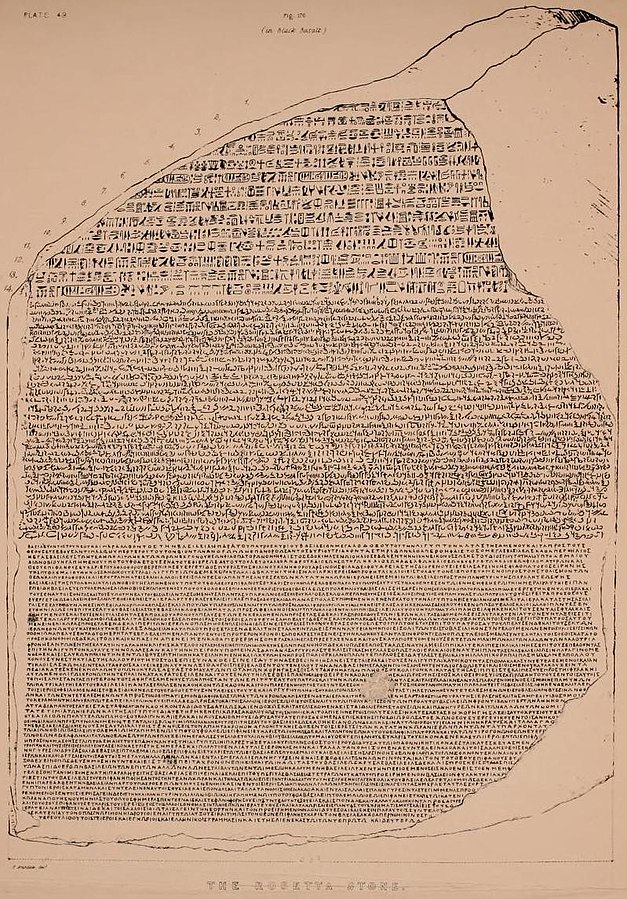

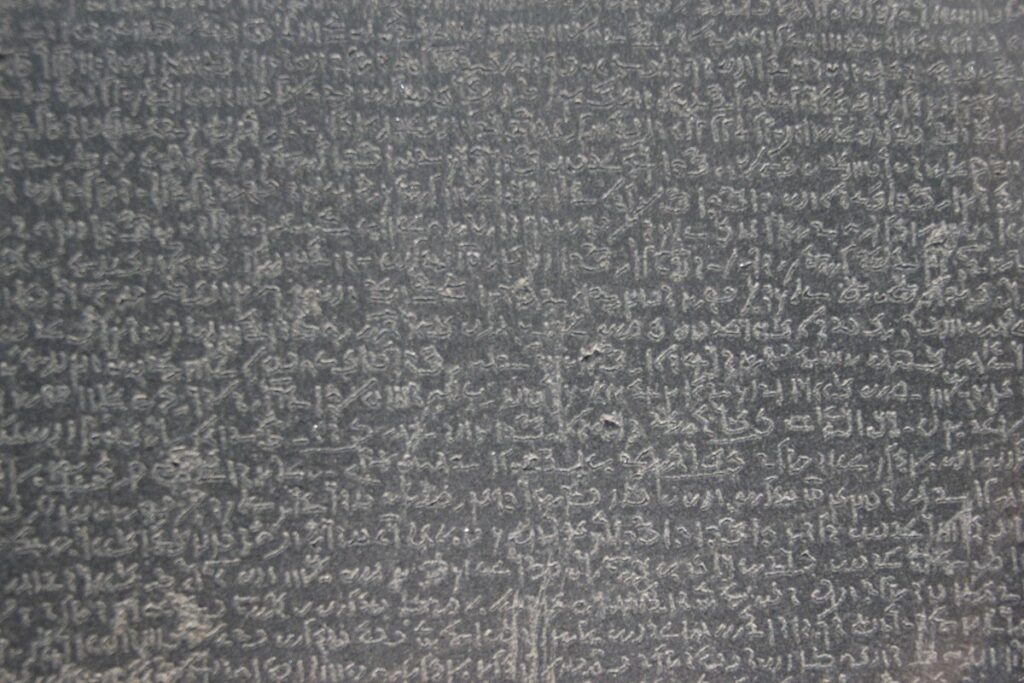

The Rosetta Stone

Discovered by Napoleon’s forces during the French campaign in Egypt (1799), the Rosetta Stone was quickly claimed by the British as part of the Treaty of Alexandria and sent to the British Museum (1802). From there, it served a central role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs and the subsequent development of Egyptology. Today, the Rosetta Stone has its own central display in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery, surrounded by information on the Stone and how it was used to decipher hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone is indispensable to the publicity of the museum and is featured strongly in advertisements for the public. On the main page of the British Museum website, the Rosetta Stone is featured as the thumbnail image leading to the gallery page, as well as the cover photo on the collection search page. It is also central to the museum shop, where dozens of souvenirs are based on, inform about, or replicate the Rosetta Stone.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) was founded in New York City in 1870 and began pursuing Egyptian antiquities in the early 1900s. In 1906, the Met initiated several long-term field archaeology projects in Egypt and was active in the region for 30 years. Its Department of Egyptian Art was also started in 1906 to manage the Ancient Egyptian collection. By this point, archaeology had begun to take a more scientific and data-interpreting approach than the antiquarianism of the 1800s, and there were more legal restrictions on the exportation of antiquities in classical countries and some in Egypt. As a result, the Met focused on assembling a collection according to more modern approaches, including obtaining classical and Egyptian antiquities largely through purchase or deals with the Egyptian Antiquities Service. They also shifted to focusing on the informative value of artifacts rather than their appeal as simple curiosities.

Today, the Met houses ~30,000 objects and pieces of Egyptian art, primarily from before the 4th century CE, which are displayed in 38 gallery rooms. These contain artifacts such as coffins and sarcophagi; amulets and jewelry; statues and statuettes of people, animals, and gods; canopic jars; stelae and stone palettes; pottery; tomb models; sections of the Book of the Dead; and more. Of this collection, the two most valuable pieces in the Met’s possession are not artifacts but two Egyptian monuments: the Mastaba Tomb of Perneb and the Temple of Dendur.

The Mastaba Tomb of Perneb (ca. 2381-2323 BCE)

The Mastaba was purchased by the Met from the Egyptian government in 1914 (figure 6). It was built in the late 5th dynasty for a state administrator named Perneb and included a limestone mastaba above the subterranean burial chamber. This mastaba, its decorative facade, and a replica of the statue chamber were transported to and reconstructed in the Met, and reveal information about funerary practices.

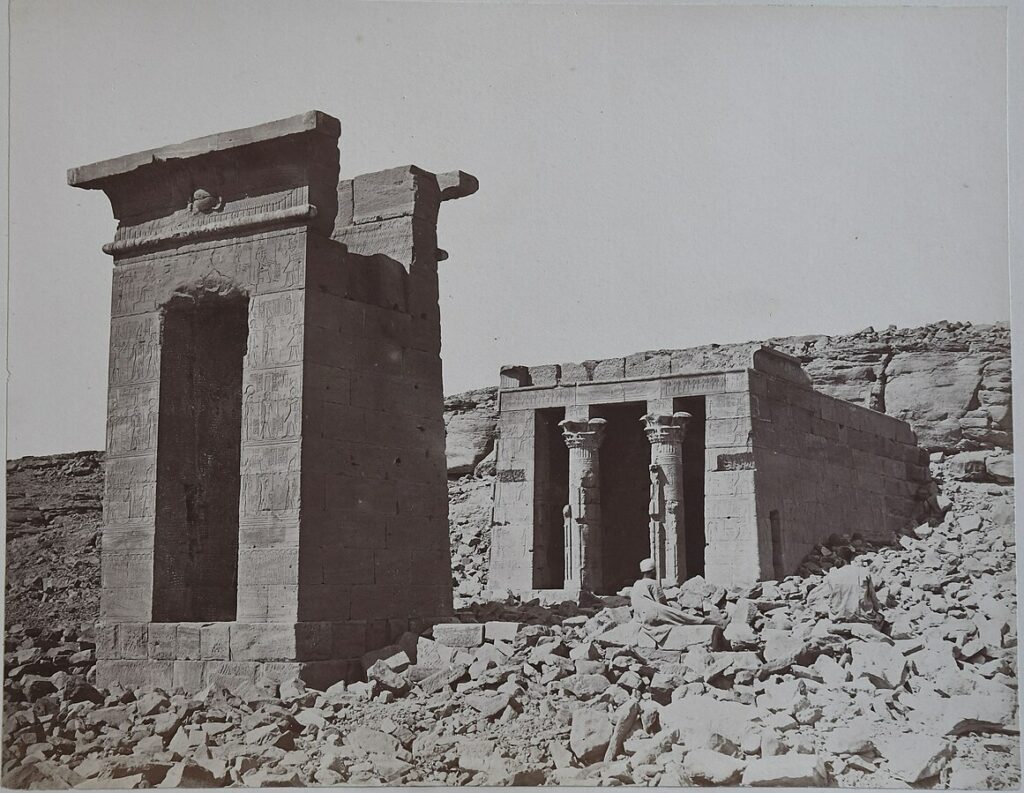

A temple from Dendur where rituals and offerings were made in service to the deity thought to reside within it. It was gifted to the U.S. government in 1965, as the temple was in danger of destruction from the rising water levels caused by the Aswan High Dam. It was dismantled and transported to the U.S., and the U.S. government awarded it to the Met in 1967. Today, the temple is a central work to the museum, where it is positioned in its own room on a platform surrounded by water, symbolizing its original position on the bank of the Nile.

Calls for Repatriation

In the past few decades, criticism of the unethical acquisition of antiquities and cultural objects by Western institutions has become increasingly visible as more and more countries and communities raise their voices to address the cultural and historical heritage they have lost. International debates over heritage, ownership ethics, and cultural patrimony have become more intense than ever before. Egypt has become an especially prominent figure in this exchange, proactively demanding artifacts such as the Bust of Nefertiti, the Rosetta Stone, and others to be returned to Egypt. Other countries have followed suit and made formal requests for the antiquities and artifacts held in museum collections to be repatriated. However, while repatriation is now strongly encouraged by entities like UNESCO (starting as far back as the 1960s), it is not required nor enforceable. It is entirely up to the institutions on whether to endorse repatriation requests, and they usually refuse.

Egypt has been unsuccessfully demanding the return of the Bust of Nefertiti from Germany’s Neues Museum for 100 years and has submitted evidence that the bust was illegally removed from the country. Egypt has also requested the return of the Rosetta Stone, as it was taken as a spoil of war and is especially valuable for Egyptian history and heritage. The British Museum has gone beyond simply denying this request and has used the Museum Act of 1963 to justify the refusal to repatriate any object in its collection. The museum and the British government continue to uphold this position. In a 2005 court case pertaining to Nazi-looted art held by the British Museum, the presiding judge, Sir Andrew Morritt, ruled that “the British Museum Act cannot be overridden by a ‘moral obligation’ to return works known to have been plundered.” Institutions, including the British Museum, promote cultural internationalism, which reiterates and reinforces the imperialist idea that artifacts of value to humanity are better off being kept in the hands of countries most fit to protect and preserve them. In maintaining these political stances, museums and Western institutions actively reaffirm processes of imperialism and continue benefiting monetarily and politically from colonial cultural extractivism.

Collectionism

One characteristic common in Western museums, and large museums in general, is the museum store. Frequently, these gift shops will have an assortment of products based on or replicating artifacts and works of art. In the gift shops of museums with Egyptian collections, Egypt is the theme for a large number of these souvenirs, which often appropriate ancient Egyptian art and culture.

The Louvre Online Gift Store

- The Louvre Shop

- 100 products under the “Egyptian antiquities” category

- Replica statues and statuettes

- Jewelry and amulets

- Accessories

- Reproduction prints

- Books

The Met Online Store

- The Met Store

- 54 Egyptian-themed products

- Information books

- Jewelry

- Replica sculptures of statues and statuettes

The British Museum Shop

- The British Museum Shop

- 279 souvenirs under “Inspired by ancient Egypt”

- 100 under the “Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt” page

- 72 based on the Rosetta Stone

- Rosetta Stone replicas

- Rosetta Stone-themed clothing, accessories, and jewelry

- Rosetta Stone USB drive

- Rosetta Stone salt and pepper shakers

- The website’s information page on the Rosetta Stone even has a link directly to this part of the online store: “For products inspired by the Rosetta Stone, visit the British Museum Shop (Opens in new window).”

- This makes it all the more clear the economic benefits the museum experiences through the Rosetta Stone and the incentives for keeping it in the museum’s possession.

Through the form of the museum store, these institutions appeal to individual collectionism, for the individual to participate in the consumption and collecting of Egypt through the purchase of these items. In this way, the influence and ownership of cultural heritage from other countries are used to monetarily benefit the institution, often using famous pieces and antiquities that were obtained during colonialism. Thus, the continued ownership of these artifacts by institutions founded on imperialism continues a process of cultural extractionism in combination with the legacies of colonialism.

Concluding Remarks

While the era of colonialism and European empires is over, its legacies continue to affect the cultural and historical heritage of people around the world. Antiquities and material culture obtained through colonization still fill the galleries of powerful museums and Western institutions, representing continuing unequal power dynamics between these nations and their former colonies. The monetary and political benefits these collections garner show how cultural extractivism continues in the museum system and acts as an incentive for the rejection of repatriation demands. These imperial attitudes continue to impact the cultural patrimony of exploited peoples under the guise of cultural internationalism. A popular debate in contemporary ethics is that of who owns heritage and the past. In response to this question, and seen through the history of museum collections, the answer appears to be that the past belongs to whomever had the power to take it.

References

Reference List

Bartman, Elizabeth. “Archaeology Versus Aesthetics: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s

Classical Collection in Its Early Years.” Classical New York: Discovering Greece and Rome in Gotham (2018): 63-84.

Bearden, Lauren. “Repatriating the Bust of Nefertiti: A Critical Perspective on Cultural

Ownership.” Kennesaw Journal of Undergraduate Research 2 (2012). https://doi.org/10.32727/25.2019.7.

“Louvre Shop.” Le Louvre. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://boutique.louvre.fr/en/.

Colla, Elliott. Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity. Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 2008.

“Collection. ”The British Museum. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/.

Duthie, Emily. “The British Museum: An Imperial Museum in a Post-Imperial World.” Public

History Review 18 (2011): 12–25. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.958068559914063.

“Egypt.” The British Museum. Accessed April 10, 2025.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/egypt.

“Egyptian Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 06, 2024.

https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/egyptian-art.

“Explore: the Rosetta Stone.” The British Museum. Accessed April 06, 2024.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/egypt/explore-rosetta-stone.

“The Guardian of Egyptian Art: The Crypt of the Sphinx.” Le Louvre. Accessed March 31, 2025.

https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/the-palace/the-guardian-of-egyptian-art.

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 2, trans. Robin Waterfield. Oxford University Press, 1998, pp.

95-168.

Keith, Lauren. “Who Gets to Tell the Story of Ancient Egypt?” Smithsonian Magazine, December

13, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-gets-to-tell-the-story-of-ancient-egypt-180981263/.

MacDonald, Sally. “Lost in Time and Space: Ancient Egypt in Museums.” In Consuming Ancient

Egypt, edited by Michael Rice and Sally MacDonald, 87-99. London: UCL Press, 2003.

MacDonald, Sally, and Michael Rice. “Introduction-Tea with a Mummy: The Consumer’s View of

Egypt’s Immemorial Appeal.” In Consuming Ancient Egypt, edited by Michael Rice and Sally MacDonald, 1-22. London: UCL Press, 2003.

Magee, Peter. “Chapter Four: The Foundations of Antiquities Departments.” In A Companion to

the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East 1, edited by D.T. Potts, 70-86. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

“The Met Store.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 14, 2025.

https://store.metmuseum.org/.

Osman, Dalia N. “Occupier’s Title to Cultural Property: Nineteenth-Century Removal of

Egyptian Artifacts,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 37, no. 3 (1999): 969-1002.

Palmer, Geraldine L. “Looted Artifacts and Museums’ Perpetuation of Imperialism and Racism:

Implications for the Importance of Preserving Cultural Heritage.” American Journal of Community Psychology 73, no.1-2 (2024): 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12653.

Riggs, Christina. “Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo

Museum.” Museum Worlds 1, no. 1 (2013): 65-84. https://login.proxy048.nclive.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/colonial-visions-egyptian-antiquities-contested/docview/1699270964/se-2.

Romo, Vanessa. “Egyptians Call for the Return of the Rosetta Stone and Other Ancient

Artifacts.” NPR, October 12, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/10/12/1128288196/egypt-calls-for-the-return-of-the-rosetta-stone-and-other-ancient-artifacts.

Stevenson, Alice. 2014. “Artefacts of Excavation: The British Collection and Distribution of

Egyptian Finds to Museums,” 1880-1915, Journal of the History of Collections 26, no. 1 (2014): 89-102. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fht017.

“Welcome to the British Museum.” The British Museum. Accessed April 14, 2025.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/.

Wikipedia contributors, “Great Sphinx of Tanis,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Great_Sphinx_of_Tanis&oldid=1264894463 (accessed April 14, 2025).

Zhu, Yuntong. “Exhibiting Colonialism and Nationalism: The Case of Egyptian Museums and Its

Cultural Heritage.” Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media 70 (2024): 8-13.