“The Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Pyramids of Giza – no comparison”

-Talib Kweli, “2000 Seasons.”

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1970s, African American intellectuals birthed Afrocentrism. Maneuvering toward racial justice, Afrocentrism emphasizes the experiences of Black people to replace the dominant Eurocentric discourse. Afrocentrists valorize Black life, culture, and history.

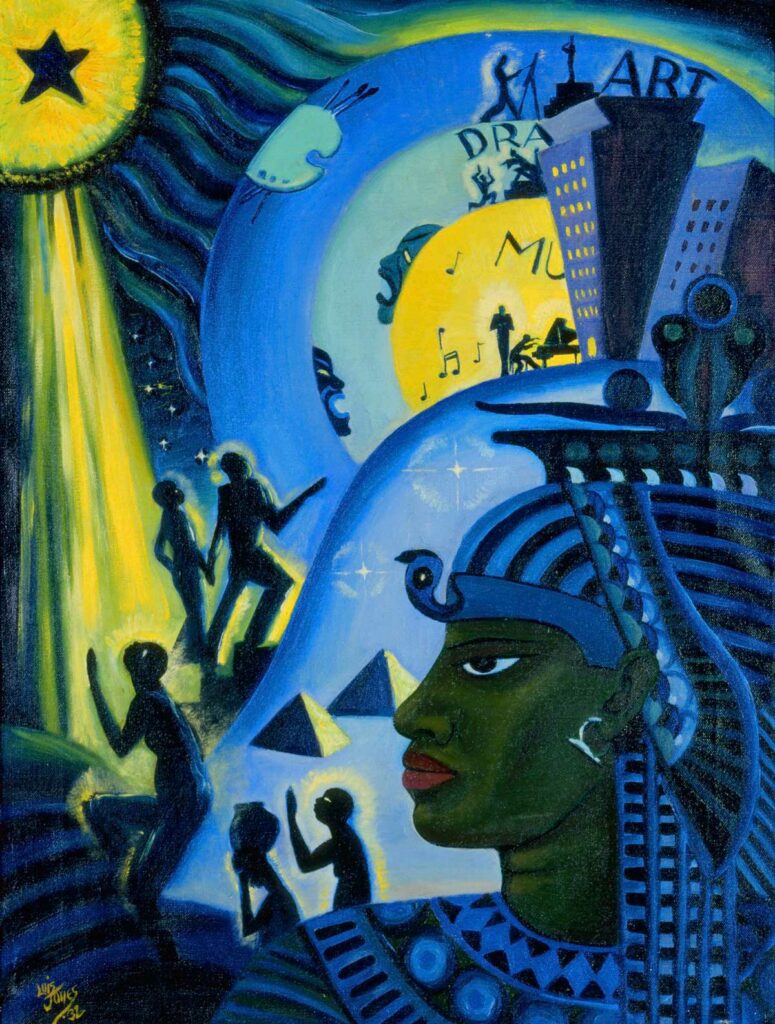

Loïs Mailou Jones, The Ascent of Ethiopia, 1932.

Claims of Afrocentrism

Egyptian themes have reoccurred in cultural productions since Egyptomania in the 1780s. Various movements in Europe have drawn from Egypt for mystic knowledge. Early Egypt-derived rites in Europe acted as a democratization of spirituality, taking away power from priests, lawyers, and kings. For instance, the ‘Religion of Reason’ during the Reign of Terror phase of the French Revolution brought Egyptian elements into Parisian discourse. Obsession with Egypt has identifiable historical roots in Western history and influenced Afrocentric interest in Egypt.

One of Afrocentrism’s central critiques of narratives of Western supremacy is the influence of Egypt on Greece. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus claimed that Greece adopted religious assemblies and parades from the Egyptian Isis festival. He also stated that the names of almost all Greek gods came from Egypt. One of the first major works that explored the sociology of Western knowledge was by Martin Bernal in his 1987 book Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Bernal and many Afrocentric scholars argue that because of the Egyptian influence on Greece, much of the foundation of Western civilization is African.

Some Afrocentrists even theorize, like Africana scholar Molefi Kete Asante, that Egypt was a Black nation. He claims that since Egypt was under foreign rule for 1300 years, “miscegenation” with settlers caused Egyptians to lose their dark skin color. The race of ancient Egyptians remains controversial due to modern hierarchies and conceptions of race being imposed on the ancient world. Contrasting Asante, many Anthropologists conclude that skin color in the ancient kingdoms paralleled the shades seen in contemporary Egypt.

The skin color controversy is one example of a weakness within the Afrocentric discourse. Often, Afrocentrists have a tendency to let their theories move too far beyond available evidence. British scholar Stephen Howe describes some extreme Afrocentric claims as even “ethno-nationalist” or “pseudoscience about melanin.” Rather than create effective strategies against systemic racism, Afrocentrism can digress from constructive conversation and evidence-based approaches. Though the movement may benefit Black mental health and self-esteem in a society dominated by white culture, it often ignores economic analyses and programs for tangible reform or concessions.

Egypt in African American Religions

African American veneration for Egypt has appeared in various religious movements in the twentieth century. The Nation of Islam and the Ansaru Allah Community, two Islam-derived faiths based in the United States, shared conflict over legitimacy in the eyes of more orthodox Islamic traditions.

The Nation of Islam

Muhammad Fard founded The Nation of Islam and passed leadership on to Elijah Muhammad. Founded on principles from Islam, The NOI gained popularity among African American during the Civil Rights era. The NOI laid some of the intellectual framework for Afrocentrism despite that many members of the Nation would disagree with it. One of the pillars of the NOI was looking back to Africa. In consequence, transatlantic Black networks and narratives were created. The NOI instructed its followers to look back to Egypt. In its religious affiliation, anti-colonial politics, and Black nationalism, the Nation of Islam viewed the Middle East as a valuable resource for African Americans. Nation of Islam narratives on history argue that a connection exists between all Black Muslims. Such a Black essentialism supports the back-to-Africa discourse that is seen in some Afrocentric theories.

Contrasting Black Muslim beliefs, Afrocentric scholar Asante rejects the necessity for Islam in resisting white supremacy. In his manifesto for Afrocentricity, he states that “If your God cannot speak to you in your language, then he is not your God.” To him, religion exists as different manifestations of cultural and spiritual beliefs. To the Afrocentric person, Asante argues, Islam is no different than Christianity, the European religion. As Christianity was spread by Europeans, Islam has an Arabizing force. Rather than religion, the core connection between all Black people is their essential Blackness.

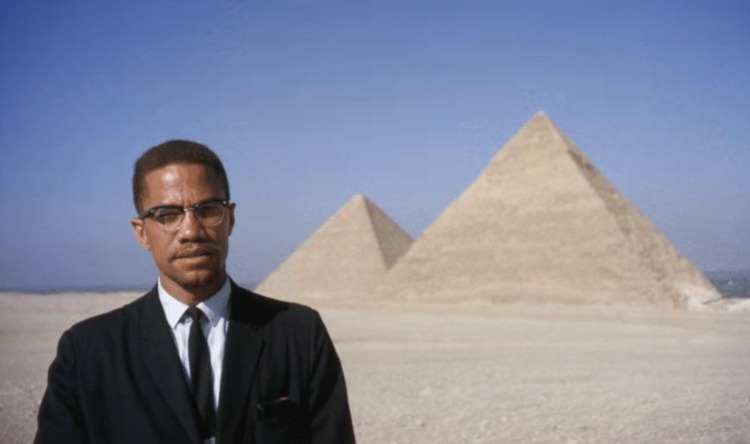

Malcom X, civil rights activist and Nation of Islam leader, stands in front of the Great Pyramids in 1964.

The Ansaru Allah Community

Another American Black spiritual group was the Nuwaubians, or the Ansaru Allah Community. Founded in the early 1970s by Dwight York, also known by the names Al Imam Isa Al Haadi Al Mahdi and Dr. Malachi Z. York, he identified himself as a descendent of the Sudanese religious and political leader Mahdi. In New York, he created an Islamic esoteric faith that drew on Egyptian mysticism for African Americans. Nuwaubian faith had roots in Islam, Christianity, Judaism, New Age religion, Ufology, Hoodoo, and ancient Egypt. Like many white communities inspired by Egypt, the Ansaru Allah Community adopted Egyptomania intellectual traditions.

Avoiding the strange and sinister legacy of this cult would not serve its victims justice. Due to terrorist threats and criticism of their beliefs, the Community relocated multiple times. York, the group’s leader, had been on the FBI’s rather since 1972. The group moved from Brooklyn to the Catskills Mountains in Upstate New York in the early 1990s. Not after long, the group migrated south to Eatonton, Georgia. There, they built a massive 476-acre commune called Tama Re. The community embellished the compound in massive ancient Egyptian pyramids and sphinxes. The FBI eventually conducted a raid and arrested York. The cult leader was sentenced to 135 years in supermax prison for a grotesque list of abuses and Tama Re was demolished.

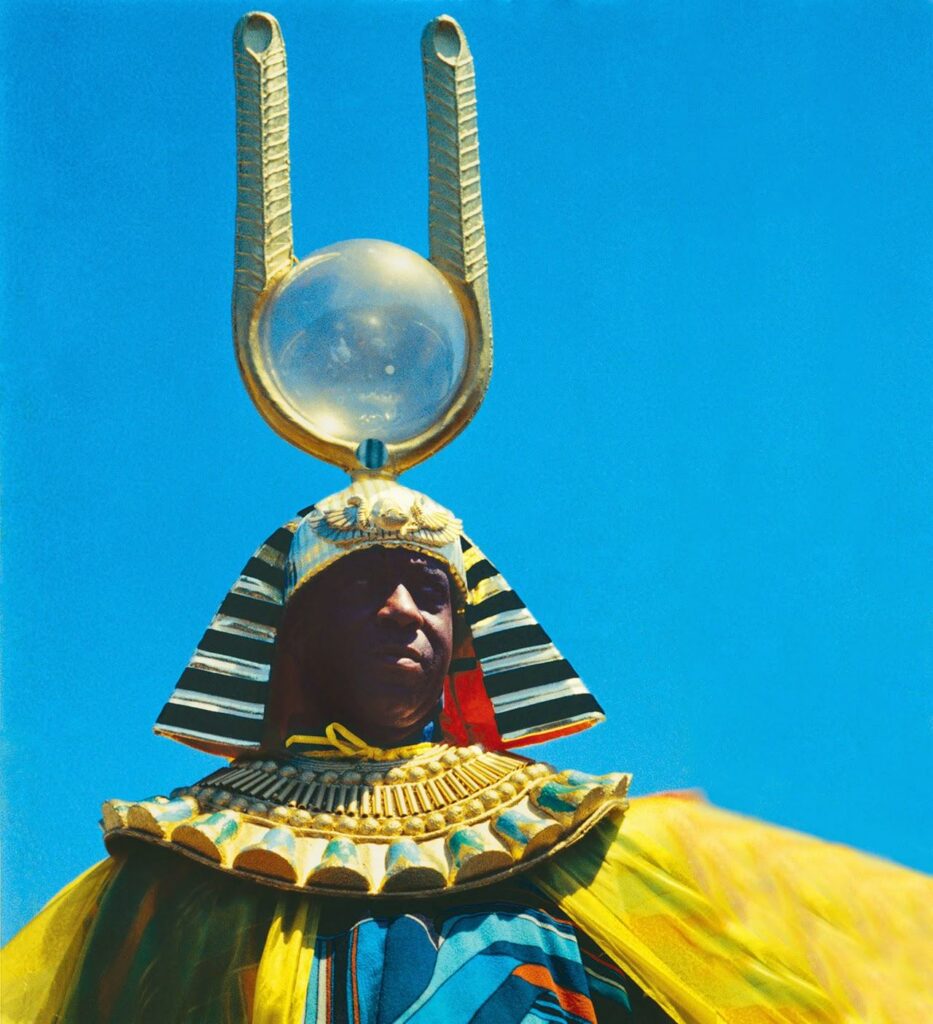

In front center is Dwight York, the founder and leader of the Ansaru Allah cult. The headwear of the men show their veneration of ancient Egypt.

Egypt in Jazz

“When the Black man ruled this land, the pharaoh was sittin’ on his throne.”

Alabama jazz musician Herman Poole Blount, known by his stage name Sun Ra, utilized Egyptian aesthetics and religious prophecy in his Afrocentric art. Sun Ra produced music apart of the jazz fusion movement which incorporates elements of psychedelic rock n’ roll into improvisational jazz.

Starring in the 1974 film Space is the Place, the movie expresses much of his Afrocentric philosophy. Sun Ra explains how all the universe is in harmony with itself except Earth. Sun Ra states that Earth is out of tune with the rest of the symphonic universe because of its oppression of Black people. To restore cosmic order, Earth must thereforebe destroyed. A select few of Black people, however, must be saved and transported on a spaceship to Saturn to create a colony free from the oppression of whites.

As evident in his stage name, Sun Ra includes Egyptian aesthetics in his art. Ra was a central deity in ancient Egyptian religion who embodied the Sun. Throughout the film, Sun Ra wears a Nemes, the crown worn by some pharaohs in ancient Egypt. In the film, a band singer also chants: “When the Black man ruled this land, the pharaoh was sittin’ on his throne.” In his art, Sun Ra has bountiful references to ancient Egypt.

Egypt in Hip-hop

Originating from the South Bronx in the 1970s, hip-hop spread across African American communities as a cultural force. Hip-hop was a new, exciting medium to communicate through sound and style. DJs remixed nostalgic R&B and soul songs to create breakbeats that invited dance and vocalization. On these tracks, emcees and singers spoke their minds.

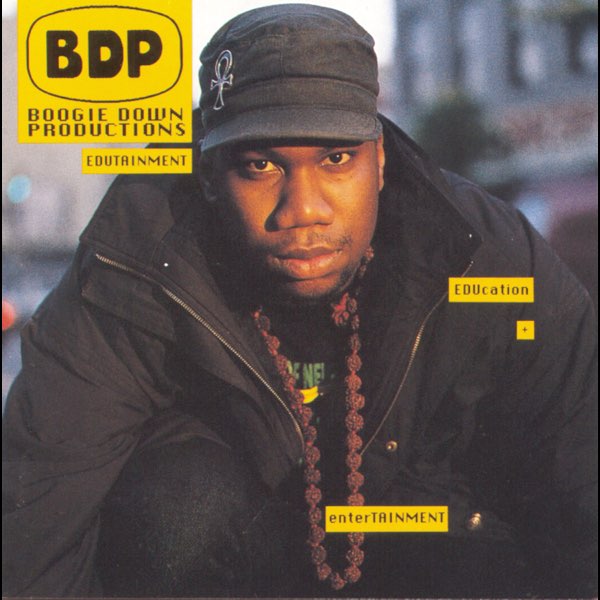

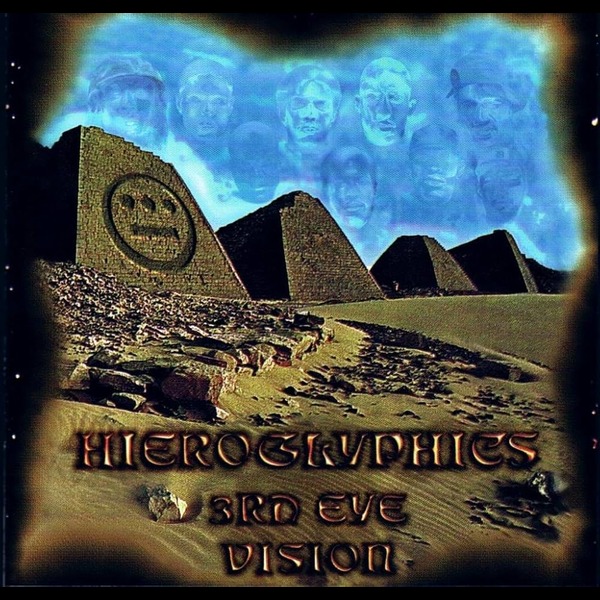

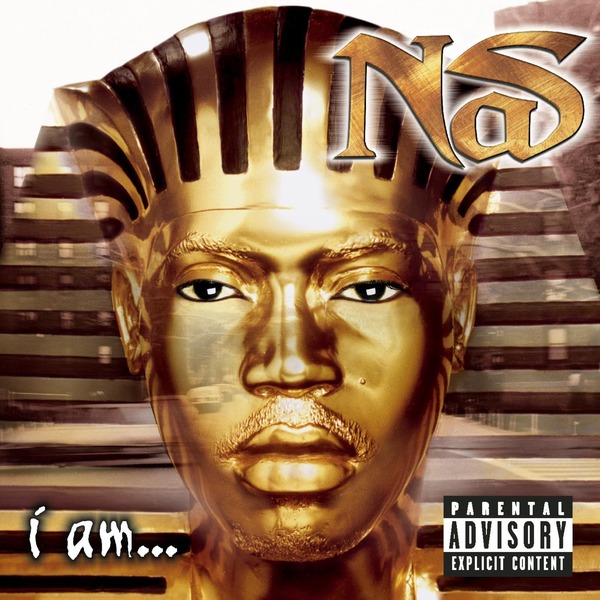

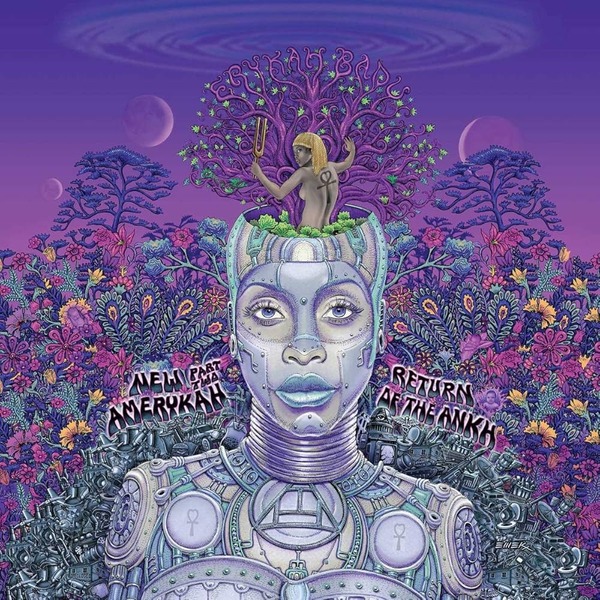

Many artists used hip-hop as a medium to advocate for social justice. In that, Afrocentric beliefs have entered the music of some rappers and singers. Ancient Egyptian symbols like the Ankh or Nemes have appeared in the aesthetic of some artists. For example, the cover of Nas’ 1999 album I am… transforms his face into a gold-plated mask like the one for the mummy of King Tutankhamun. In his track “I Can,” Nas invokes themes of Egyptian influence on Greece by rapping: “Egypt was the place that Alexander the Great wen, he was so shocked at the mountains with Black faces.” Hip-hop has existed as a culture which produces Afrocentric discourse on Egypt. Below are album covers by hip-hop artists that contain ancient Egyptian themes.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Badu, Erykah. New Amerykah Part Two: Return of the Ankh. Universal Motown Records, 2009.

Boogie Down Productions. “Blackman in Effect.” On Edutainment. Zomba Recording, 1990.

Coney, John. Space is the Place. 1974.

Herodotus. “Book Two.” In The Histories, translated by Robin Waterfield, 95-163. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Hieroglyphics. 3rd Eye Vision. Oakland: Hiero Imperium, 1998.

Nas. “I Can.” On God’s Son. Sony Music Entertainment, 2002.

–––. I Am…. Sony Music Entertainment, 1999.

Secondary Sources:

Asante, Molefi Kete. Afrocentricity: The Theory of Social Change. Chicago: African American Images, 2003.

Bernal, Martin. Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Curtis, Edward E. Black Muslim Religion in the Nation of Islam, 1960-1975. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Howe, Stephen. Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. London: Verso Books, 1998.

Knight, Michael Muhammad. Metaphysical Africa: Truth and Blackness in the Ansaru Allah Community. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2020.

“Nuwaubian Nation of Moors: SPLC Designated Hate Group.” Southern Poverty Law Center.