“I then with precaution made the hole sufficiently large for both of us to see. With the light of an electric torch as well as an additional candle, we looked in. Our sensations and astonishment are difficult to describe as the better light revealed to us the marvelous collection of treasures.”

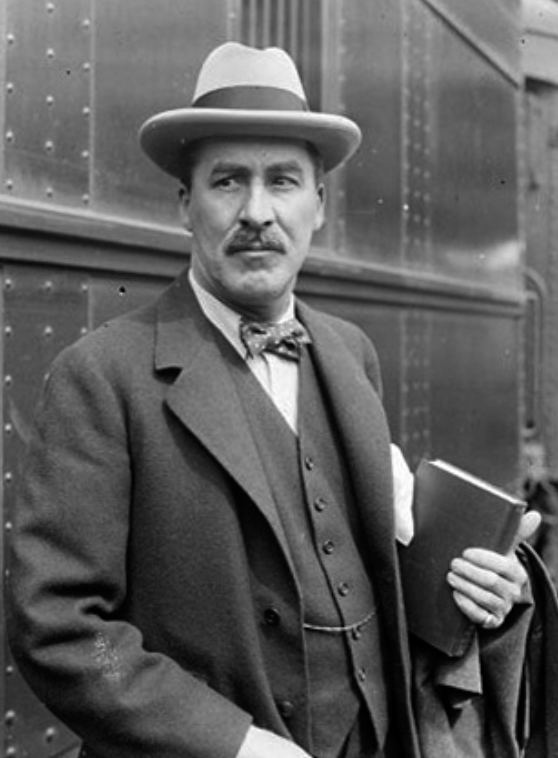

~Howard Carter

Carter’s words exemplify the mysticism of archaeological discovery, the power of discovering something that’s been lost for so long…

This moment was more than that though; the unsealing of the tomb would become emblematic of a much deeper struggle over colonialism, nationalism, and collective identity. The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 saw Egyptian nationalists rebel against Britain after nearly half a century of colonial rule; the British were able to quell the revolution in the moment, but ultimately knew that their hold on the country in its entirety could not stand.

In 1922, Egypt officially became independent, although British influence remained a powerful force culturally, politically, economically, and archaeologically. That the tomb was discovered that very same year proved to be significant. Coinciding with a rising tide of nationalism, the discovery meant that the battle which Egyptians were embroiled in was one not just over sovereignty, but over history itself.

A Battle over History: Imperialism, Colonialism, & NAtionalism

This timeline briefly highlights important events around the discovery and excavation of King Tut’s tomb.

The Nationalist Response

Nationalist leaders in Egypt sought to use the King Tut moment to promote ideas of self-sovereignty and the reclamation of Egypt’s ancient past from imperial powers. This was reflected in leaders like Zaghlouol, but also years later in Gamal Abdel Nasser, who continued to use Egytpt’s history as a way to elevate its future.

Sa’ad Zaghloul

Leader of the Wafd Party

Gamal Abdel-Nasser

President of Egypt, 1954-1970

Lasting Impact

the Egyptian Antiquities Service

In 1952, Mustafa Amer became the first Egyptian to head the Antiquities Service; this move was symbolic and practical, finally placing authority in the hands of one of Egypt’s own after centuries of colonial control. This change would not have been possible if not for the prolonged struggle beginning decades before among Egyptian nationalists of the 1920s, who fought for Egyptian autonomy over its heritage in the wake of the discovery of the tomb.

museum leadership

Transformations in museum leadership and practices reflected the impact of the discovery of the tomb and its connection to nationalism. Museums in Egypt long reflected its colonial past — many were founded in the wake of the French occupation of Egypt, and leadership of museums was often dominated by foreigners. The rise of nationalism meant that museums shifted to reflect Egypt’s reclamation of its past. Following Nasser’s rise to power in the 50s, the museum finally came under the direction of Egyptians themselves.

Education

The discovery of the tomb and its aftermath had a powerful impact on education, and specifically, the recognition of the importance of teaching future generations of Egyptians about the country’s pharaonic past. Schools of Egyptology within Egypt itself became more robust following the nationalist movement and the discovery of the tomb, ensuring that exploration of Egypt’s past would lay in the hands of its own people once and for all.

the bottom line

- Both colonialists and nationalists attempted to use the discovery of the King Tut’s tomb to push their own narratives.

- Though this story takes place in Egypt, countless cultures and groups around the world have used Egypt in similar ways; explore the other pages under “Using Egypt” to see just how widespread the cooptation of this culture has been!

Bibliography

Carter, Howard. Journal, Season 1922-1923. The Griffith Institute. Accessed March 31, 2025. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/discoveringtut/journals-and-diaries/season-1/journal.html.

Gifford, Jayne. Britain in Egypt: Egyptian Nationalism and Imperial Strategy, 1919–1931. London: I.B. Tauris, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781838604967.

“Lord Carnarvon’s Plans.” The Times, January 10, 1923. London. https://nelcdh.ds.lib.uw.edu/tutankhamun-centenary/files/show/144.

Nasser, Gamal Abdel. Egypt’s Liberation: The Philosophy of the Revolution. Cairo: Cairo Press, 1954. Provided in His 372: Egypt from Soup to Nuts, taught by Dr. Berkey, Department of History, Davidson College, Spring 2025. file:///Users/charlotteweis/Downloads/Nasser.Egypts%20Liberation.excerpts%20(3).pdf.

Reid, Donald Malcolm. Review of Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, vol. 3: From 1914 to the Twenty-First Century by Jason Thompson. Journal of the American Oriental Society 141, no. 3 (July-September 2021). https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/jameroriesoci.141.3.0700.

Riggs, Christina. “‘Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo Museum.” Advances in Research – Museum Worlds 1 (2013). https://www.academia.edu/12439652/_Colonial_visions_Egyptian_antiquities_and_contested_histories_in_the_Cairo_Museum_Advances_in_Research_Museum_Worlds_1_2013_.