Cleopatra’s Suicide In Western Visual Art

Before you read any further,

imagine what Cleopatra looks like in your mind. What kind of images appear? Do you picture blue eyeshadow and sharp black eyeliner? Perhaps she is adorned with gold jewelry and flowing clothing. You might even think of a Cleopatra character from a movie, video game, or book.

It may come as a surprise, then, that historians remain uncertain about Cleopatra’s exact physical appearance.

In fact, the only authentic images of the Egyptian queen are coin portraits issued during her lifetime. If we cannot fully reconstruct Cleopatra’s appearance, how did her legacy shift from that of a powerful political figure—worthy of being minted on currency—to the image you just imagined?

Explore the rest of this page to see how Western visual artists have remembered Cleopatra, and how their depictions have shaped contemporary views of her and her political legacy.

Cleopatra’s biography

Did you know…

Historians do not know exactly how Cleopatra took her life, but myths and legends claim she used the poison from an asp, or Egyptian cobra. Nonetheless, most artistic and literary depictions of her death feature a snake.

Cleopatra’s death in Western Visual Art

Cleopatra by Giampietrino

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1520-1540

Medium: Oil on painting, mounted on mahogany

Dimensions: 75.9 x 53.7 cm.

Repository: Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH

Tall Drug Bottle with the Death of Cleopatra by Orazio Pompei

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1540-1550

Medium: Tin-glazen earthenware

Dimensions: 43.97 x 20 cm.

Repository: The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

The Death of Cleopatra by Guido Cagnacci

Year(s) Constructed: c. 1645-1655

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 95 x 75 cm.

Repository: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

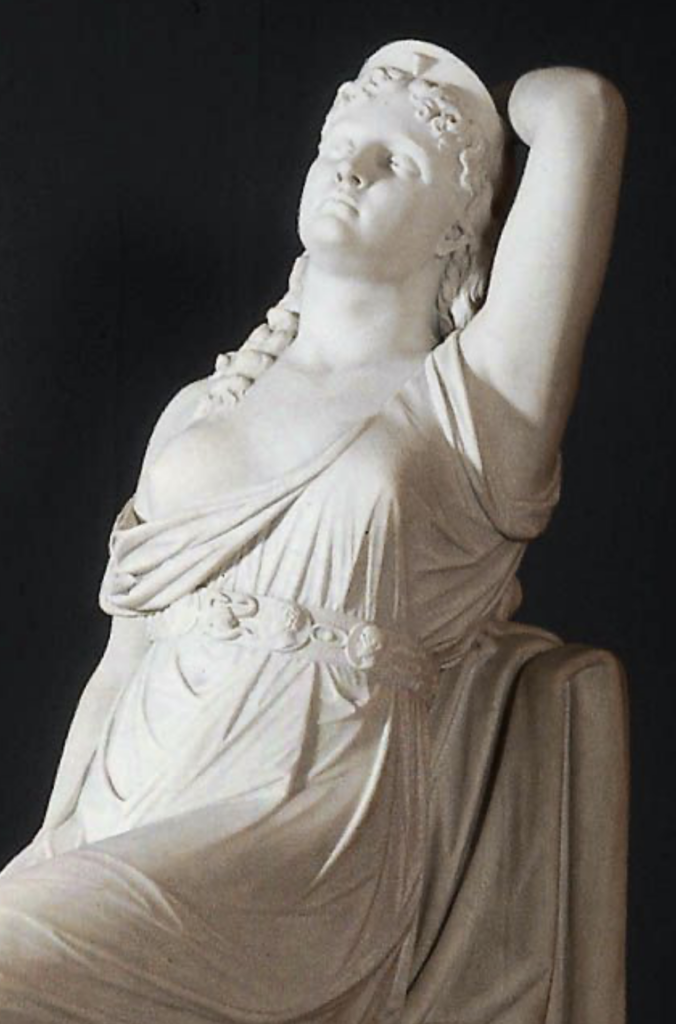

Cleopatra by Thomas Gould

Year(s) Constructed: 1873

Medium: Stone and marble

Dimensions: 144.78 x 63.86 x 125.73 cm.

Repository: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

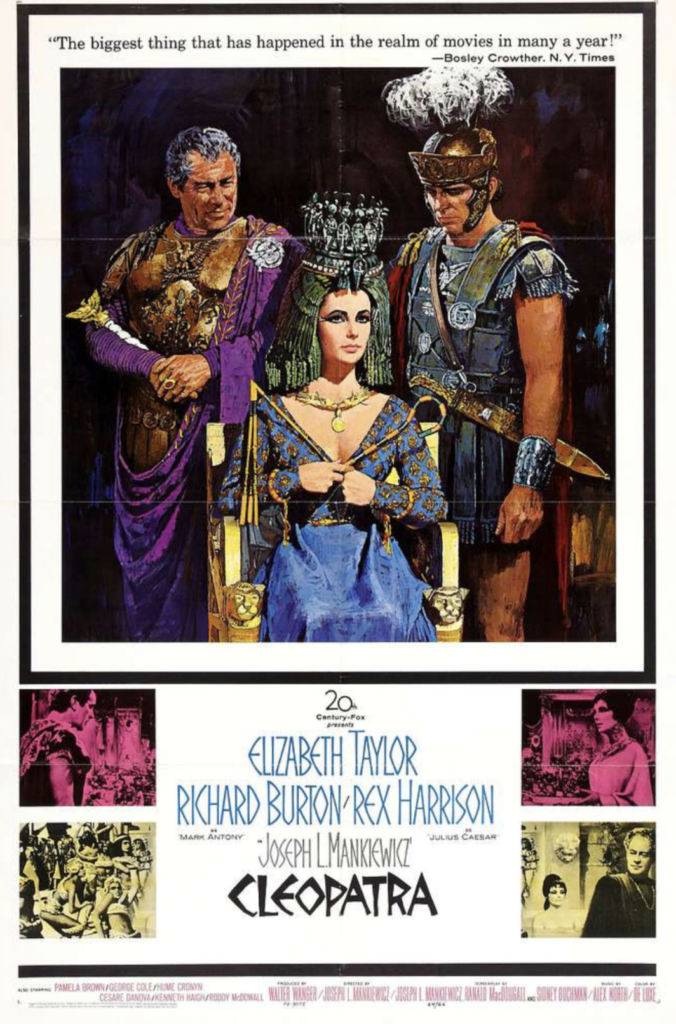

Cleopatra, directed by Joseph Mankiewicz, starring Elizabeth Taylor

Release Date: June 12, 1963

Genre: Drama, Romance

Runtime: 4h 10min

Watch This Clip of Cleopatra’s Death Scene:

Image Themes

The five visual images above represent just a sample of how the West has remembered Cleopatra. While thousands more exist, these examples highlight recurring themes in Western depictions of the Egyptian queen. As noted earlier, historians remain uncertain about Cleopatra’s appearance and the circumstances of her death—yet Western portrayals of her death often look remarkably similar.

Let’s now explore how Western visual artists have Westernized, sexualized, and commodified Cleopatra’s image, shaping the way you may picture her today.

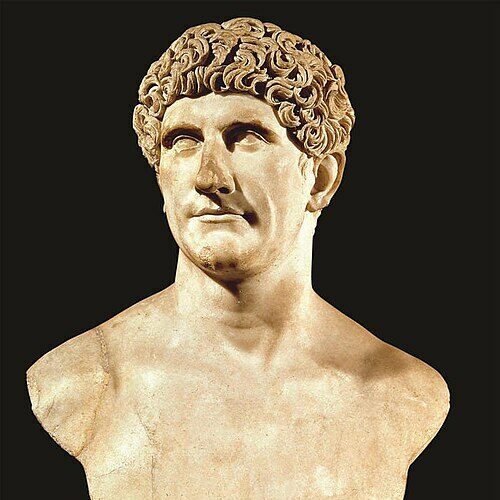

WESTERNIZATION

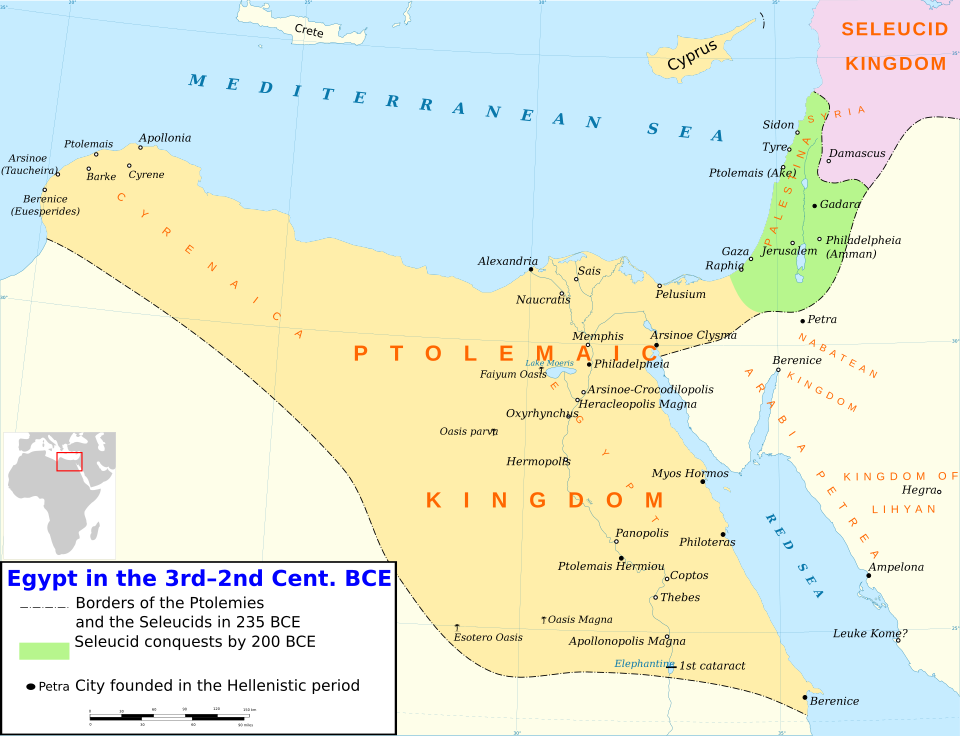

Cleopatra’s image has been Westernized by these visual artists, actively recasting Cleopatra as a symbol of an imagined East, reinforcing Western cultural dominance and diminishing her role as a strategic ruler.

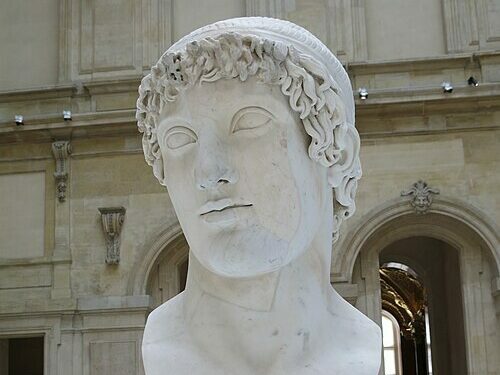

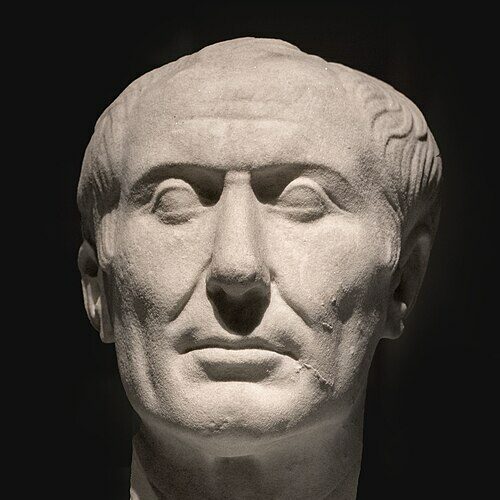

Although Cleopatra was of Greek descent, she likely did not have fair skin comparable to that of Western Europeans. Yet, these artists consistently portrayed her to resemble the women of their own countries.

Cleopatra appears more like a Renaissance woman than an Egyptian queen. By using themes of classicism and humanism, these artists have diminished the political significance of her death.

The Orientalist use of highly saturated hues like yellow and turquoise portrays the Egyptian queen in a fundamentally different light—reinforcing Western views of nations like Egypt as exotic and subordinate.

In Cleopatra (1963), the music during her death scene features oboes and tambourines, creating a mysterious and foreign soundscape that reflects Western perceptions of non-Western women.

All of the images in this analysis depict Cleopatra with a small nose, pink lips, clear skin, no body hair, and passive or submissive expressions. By applying Western beauty standards, these artists have erased Cleopatra’s traditional Egyptian features.

SEXUALIZATION

By sexualizing Cleopatra’s image, Western artists have shaped her legacy as that of a beautiful and erotic seductress rather than a strong and formidable political leader.

Gould’s unnatural posing of Cleopatra’s body portrays the Egyptian queen as vulnerable and disempowered rather than composed and authoritative.

By portraying Cleopatra selectively removing her clothing and revealing her nude body, these artists highlight her as a sexual object rather than a powerful political figure.

Cleopatra’s nudity in these images is not incidental but a deliberate choice by the artists. The frequency of such depictions suggests that popular culture and commercial markets favored eroticized portrayals of non-Western women.

None of the images depict Cleopatra with pubic hair, presenting her as a pure—and possibly youthful—sexual figure. These choices eroticize her, reducing a politically astute queen to an exoticized symbol and reinforcing colonial and patriarchal narratives.

COMMODIFICATION

By commodifying Cleopatra’s image, Western visual artists have repurposed her identity for commercial and domestic use, reinforcing her status as a marketable symbol rather than a historical leader.

The use of Cleopatra’s image in films and popular culture has sparked a new wave of Egyptomania, shaping how broader audiences imagine Cleopatra and other non-Western female political figures.

By placing Cleopatra’s image on everyday objects like bottles, these artists have commodified a selective portrayal of the queen for mass consumption, leaving audiences unaware of her political legacy.

Conclusion

Cleopatra’s death has long captivated Western visual artists, but their depictions have largely reflected the fantasies and ideologies of their own cultures rather than the reality of Cleopatra as a political figure. Across time periods and mediums, artists have Westernized, sexualized, and commodified the Egyptian queen, casting her as an eroticized spectacle rather than a sovereign leader. Ultimately, these depictions of Cleopatra not only distort her legacy but also reveal how art, shaped by Western ideals, continues to silence the voices of powerful women who shaped history on their own terms.

Suggested Reading

Bahrani, Cyrino. Women of Bablyon: Gender and representation in Mesopotamia. Routledge, 2001.

Roller, Duane. Cleopatra: A Bibliography. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. Vintage Books, 2008.

Schiff, Stacy. Cleopatra: A Life. Back Bay Books, 2011.

Thompson, Jason. A History of Egypt: From Earliest Times to the Present. Anchor Books, 2008.

Walker, Susan and Peter Higgs. Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth. Princeton University Press, 2001.