In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Anna Kathryn Kilby is a sophomore potential Gender and Sexuality Studies and Political Science major at Davidson College.

Mary Lacy, wife of Davidson College President Drury Lacy, took her job as First Lady of the college very seriously. In her letters to her stepdaughter, Bess, she writes of cooking the best food, wearing the best clothes, and making sure people at the college are taken care of, including her own slaves. She also expresses her frustration at her female slaves when they grow ill but doesn’t address their work in the home directly. Mary Lacy seems to be striving for domestic perfection, but how much of her efforts are hers, and how much effort belongs to her female slaves?

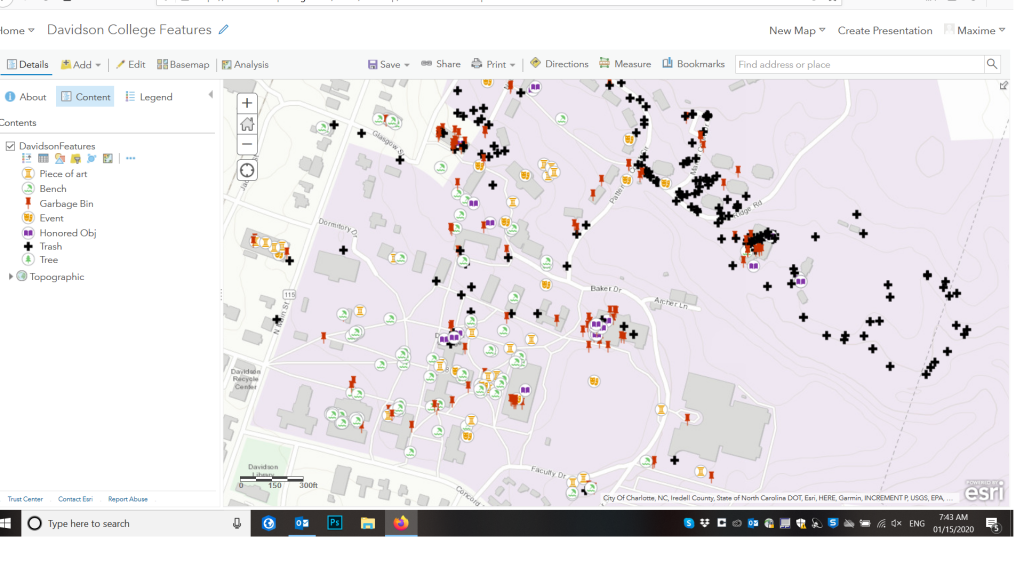

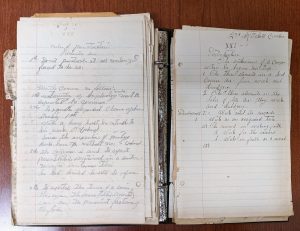

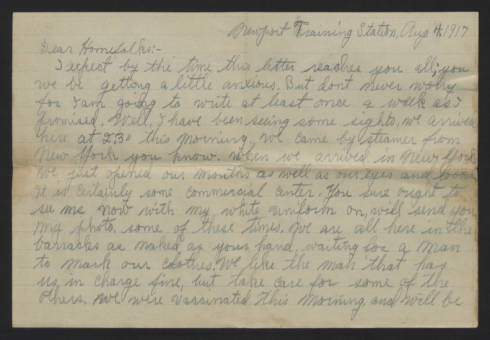

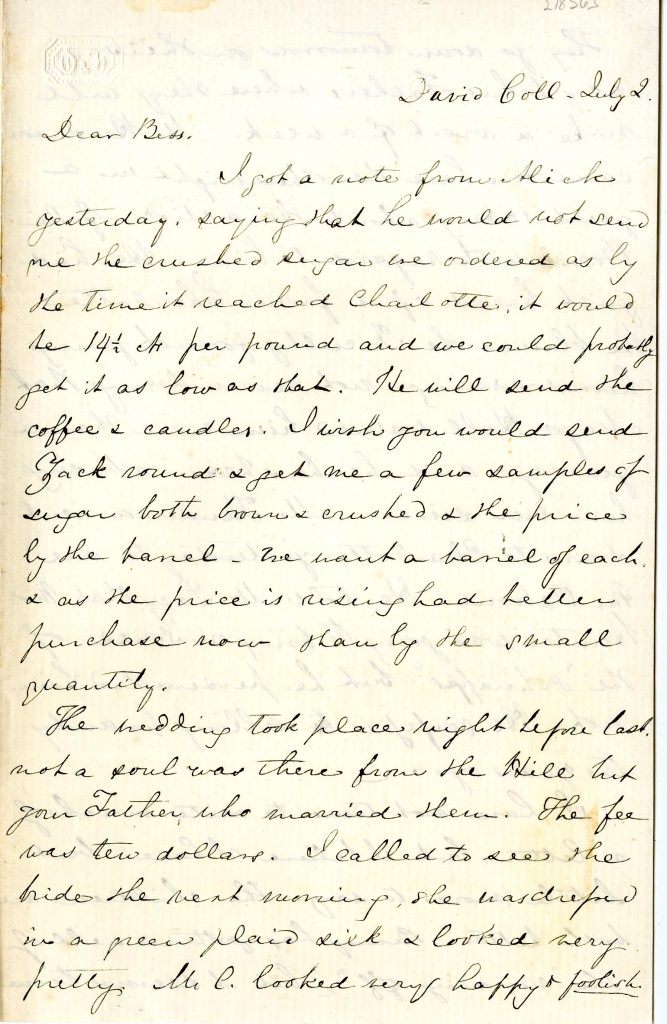

Mary Lacy was Drury Lacy’s second wife. He served as president of Davidson College from 1855-1860, and, during this time, their family lived across from the college, where the Belk Visual Arts Center is now. Drury Lacy had children from his previous marriage, one of which was Elizabeth, or Bess, as Mary called her, whom Mary writes her letters to. Bess lived in Charlotte with her husband. Mary wrote her letters to Bess from 1856-1859 while her husband served as president1.

As First Lady of Davidson, Mary’s duties consisted of hosting guests of the college and making sure she was the perfect hostess. In her first letter from July 1856, she asks Bess about crops and food products, and then in the next letter she discusses dresses and blankets. In a December 1858 letter, Mary tells Bess of a purple scarf from New York that is “the exact shade of her bonnet strings” and tells Bess to send her furs if she won’t wear them. Throughout the letters, Mary often talks about both male and female guests staying with them. Mary’s quest to be the best housewife is evident. She clearly needs to look the part, act the part, and cook like the part.

So much of Mary’s perfect image was due to her domestic enslaved women, a few of which she mentions in her letters. In a letter from August 1856, she writes about the inconvenience of enslaved woman “Aunt” Amy getting sick, and then expresses displeasure when another enslaved woman shows symptoms, claiming “Aunt” Maria was faking it to get time off from work. Mary calls Maria a “hard old case.” The state of these enslaved women is so frustrating to Mary because she needs them to upkeep her image. How could she possibly be the best first lady, host, and housewife without the help of her domestic bondwomen? She calls in doctors to help with Aunt Amy’s illness, but I assert that this is not out of compassion for Amy, but out of selfish concern. Without enslaved women like Aunt Amy and Aunt Maria, Mary’s image would deteriorate. These enslaved women shaped Mary’s identity, and got none of the credit. Readers can wonder which meals Mary actually cooked, which clothes she actually sewed, which guests she actually took care of, and which efforts were actually hers.

Bibliography

Admin, Davidson College HIS 306 Spring 2017. “Introduction.” The Mary Lacy Letters. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/

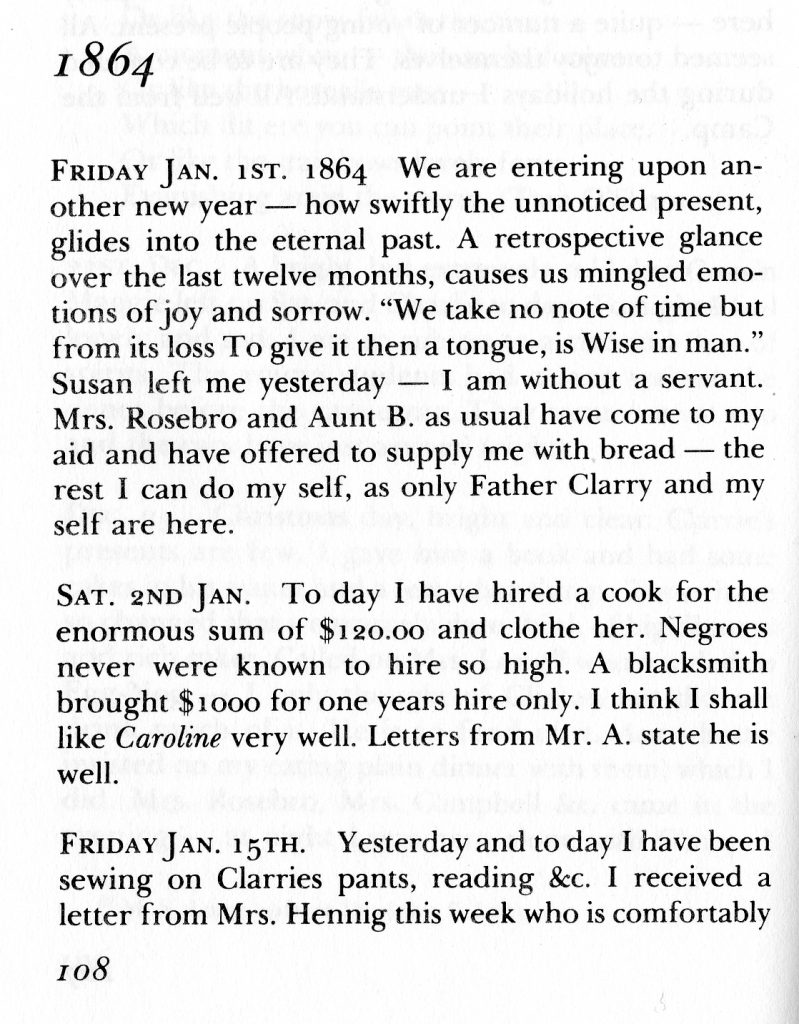

Lacy, Mary. “Letters and Transcriptions.” The Mary Lacy Letters, Davidson College. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/