In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Ellie Hudson is a senior from Asheville, North Carolina. She is a Communication Studies major and a Hispanic Studies minor.

Davidson College, like many colleges in the United States, was built by enslaved people, many of whom are absent from the documentary record. Recently, there have been efforts by colleges around the country to study and acknowledge the role that slavery played in the institution’s history. In 2017, a family contacted Davidson about one of their ancestors, an enslaved woman named Betty Tate Davis, who made the bricks that were part of one of the original Davidson buildings.

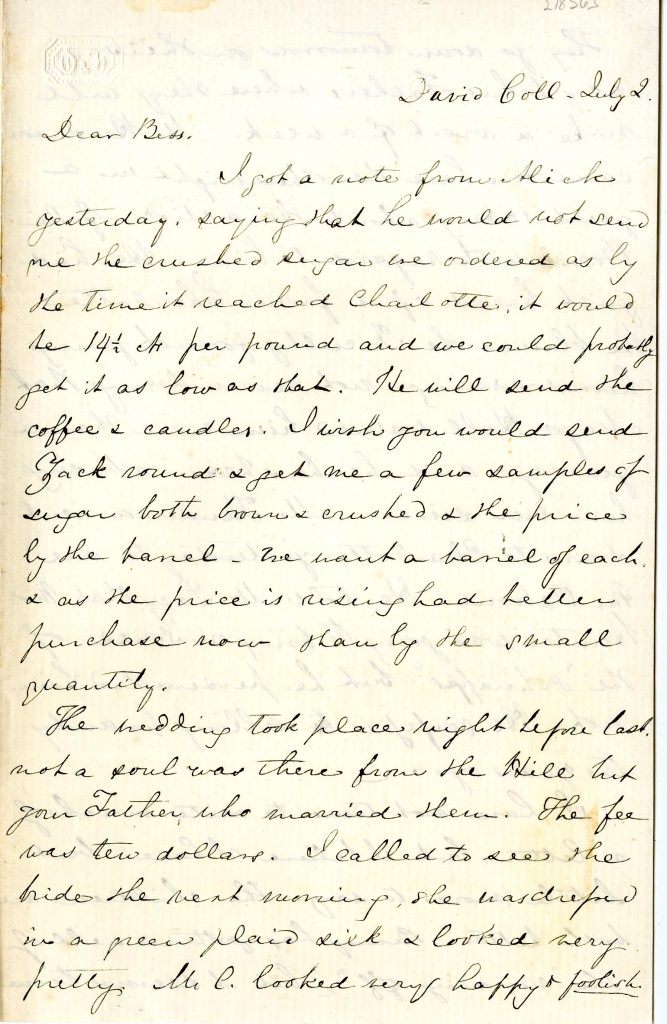

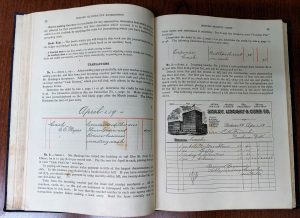

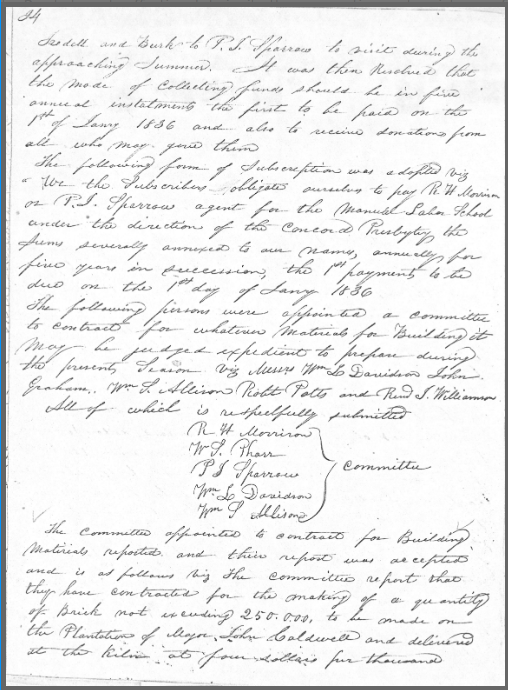

Starting in 1835, the Presbytery of Concord began meeting to discuss the founding of Davidson College. Mecklenburg locals were contracted by the Presbytery to provide services aiding in the construction of the College. In August of 1835, a committee was formed to manage the acquisition of building materials. The committee resolved to purchase bricks from the plantation of Major John Caldwell, where Betty Tate Davis may have been enslaved. The minutes read, “The committee report that they have contracted for the making of a quantity of Brick, not exceeding 250,000 to be made on the Plantation of Major John Caldwell and delivered to the kiln at four dollars per thousand.”1

Unfortunately, we are unable to obtain details from the documentary record about Betty Tate Davis’s life in Mecklenburg County. We can infer that she was most likely enslaved on Major John Caldwell’s plantation by connecting her family’s oral history and the Presbytery minutes. Betty Tate Davis is one woman, but her absence in the historical narrative is important. There were many enslaved people that worked to construct and maintain Davidson College whose stories are missing just like Betty Tate Davis’s. The reality is that the uncompensated and often unrecorded labor of enslaved people made Davidson College what it is today. At any academic institution, it is critically important that we work to understand our past and how it informs our present. At Davidson, we must reckon with the legacy of slavery in order to complicate the historical narrative we are often presented by the College. When we look to stories like that of Betty Tate Davis and those like her, we can begin to gain a broader, more intersectional, and more realistic understanding of the history of Davidson College.

Bibliography:

Presbytery of Concord. Presbytery Minutes. August 1835. Concord Presbytery Records. Davidson College Archives and Special Collections.