In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Written by Ella Nagy-Benson, a sophomore History major from Middlebury, Vermont. Ella is involved in Warner Hall Eating House and is an editor for the Davidson History Journal.

Feminist historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich once said that “Our connection to the past… is through the stuff that is left behind… without documents, there’s no history, and women left very few documents behind.”1 Historical materials such as letters or diaries often seem to hold only trivial information, yet they can actually provide important insight about a time period. Luckily, The Davidson College Archives houses a collection of letters written by Mary Lacy, the wife of Reverend Drury Lacy, who was president of Davidson College from 1855 to 1860. These letters help us understand her role as a slave-owning woman, specifically the race-relations in Davidson during this time. Her writings show that slave labor was a central aspect to her household and that women contributed to the management of slaves.

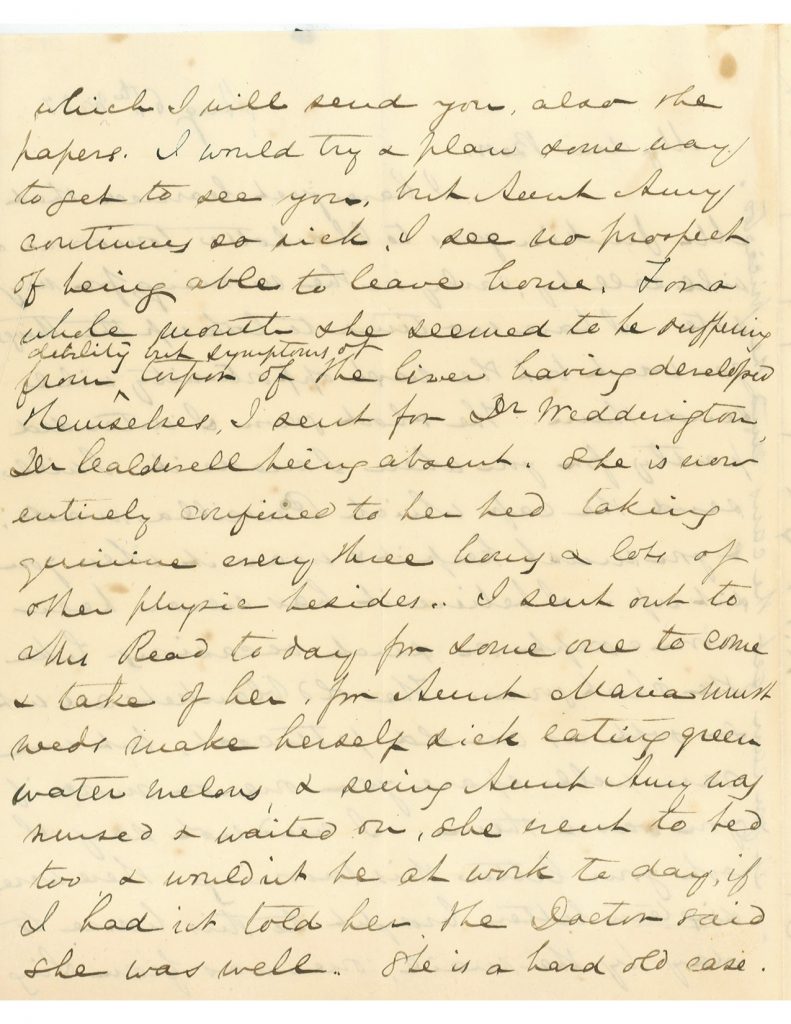

One of Mary Lacy’s letters dated August 6th, 1859, which she sent to her stepdaughter, Bess, provides a glimpse into her interactions with the household slaves, particularly one named Aunt Amy. She writes about how “for a whole month [Aunt Amy] seemed to be suffering from debility,” yet Mary was reluctant to believe her until the doctor “confined her to bed.” 2 In another instance, she refers to a different slave as a “hard old case” for trying to take a break from work.3 The language Mary uses is laced with condescension and annoyance. It shows how in many ways, she was indifferent to these women—she saw them as her workers, first and foremost. Any sign of sympathy she showed regarding her slaves’ health likely had an ulterior motive of needing them to be able to work so they could provide for her again.

Often, society romanticizes Southern Antebellum women as graceful, charming belles. However, this image is narrow and idealized because in reality, slave-owning women partook in the realities of slavery, which meant that they used their privilege and power to “manage” their slaves in ways that were coercive and sometimes even violent. The societal implications of slavery meant that many women taught their daughters how to manage slaves through tactics of punishment and control.4 This concept challenges the stereotype of Southern white women as pious and submissive and helps us understand why women like Mary Lacy viewed their slaves as property. As we study Davidson’s history, we must remember the institution’s ties to slavery and understand that all people who owned slaves on campus were involved in its brutal effects—even women. These letters provide powerful details which emphasize how Mary Lacy used her privilege of owning slaves to enjoy a lifestyle that she otherwise would not be able.

Works Cited:

Lacy, Mary. Mary Lacy to Bess Dewey, 6 August 1856. In The Mary Lacy Letters: https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com.

Stephanie Jones-Rogers, “Mistresses in the Making,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, 8th. ed., ed. Linda K. Kerber, et al. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 139.

Speak Your Mind