This post was written by Alice Garner, a member of the Class of 2024, for an assignment in Dr. Devyn Spence Benson’s AFR 101: Introduction to Africana Studies class. For the past five years, the Africana Studies Department has collaborated with Davidson College Archives, Special Collections and Community to uncover the experiences of Black individuals at the college. Garner is an intended Psychology Major and possible Latin American Studies minor from Norwich, Vermont. Her interests include the intersection between the African diaspora and Latin American history and childhood developmental psychology.

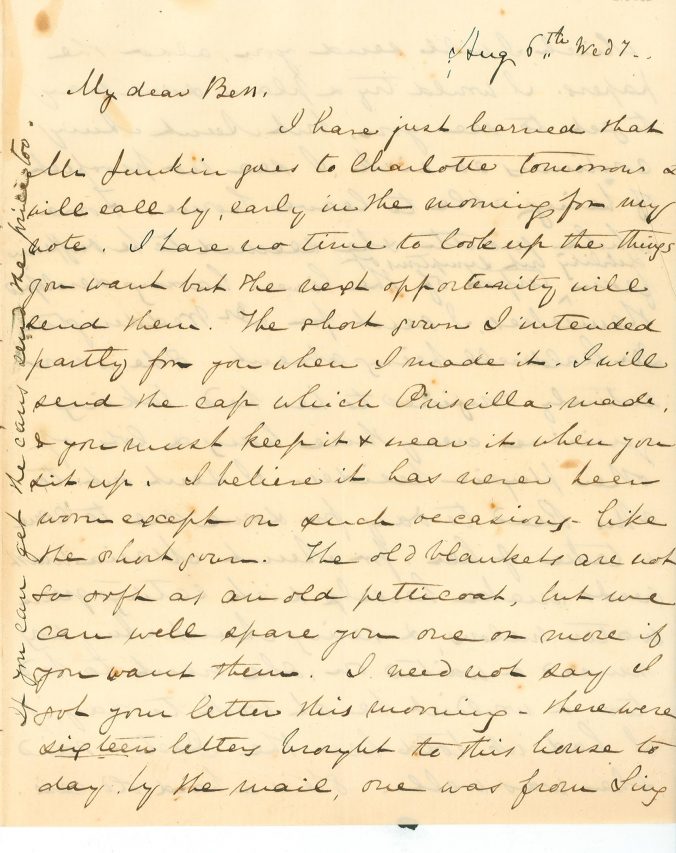

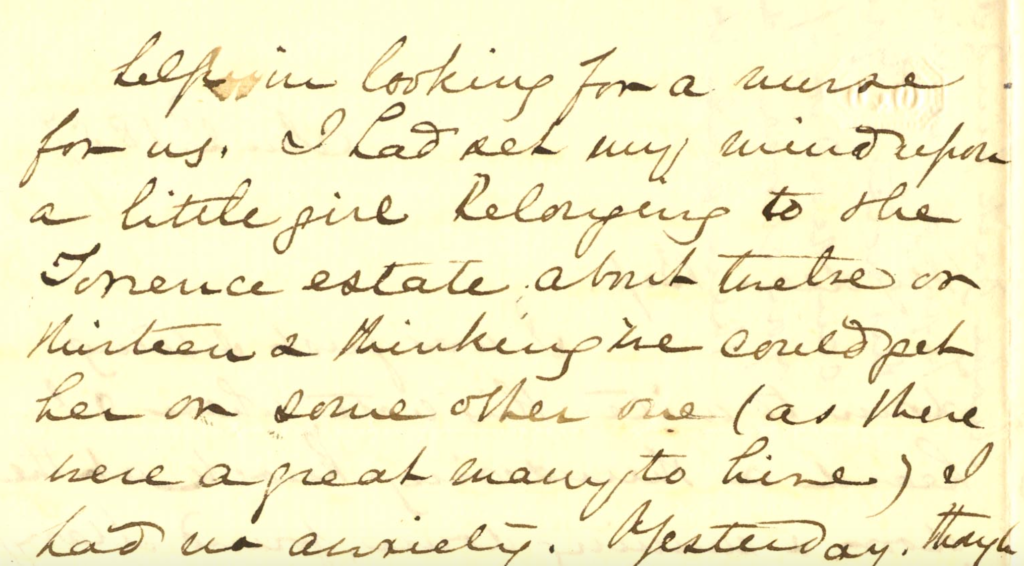

Trapped in a subordinate position within society, Mary Lacy took pride in controlling the slaves within her household, using it as a way to forge her own identity. Women, such as Mary Lacy, were merely viewed “as a unit of production and reproduction under men’s dominance,” as they were denied the ability to form their own opinions or ideals as a whole.[1] The normative for women in society was to succumb to coverture: a concept that a “married woman had neither independent minds nor independent power.”[2] In an attempt to distinguish her place in the patriarchal realm, “[to] encompass [a] feeling of identification,” Lacy derived “principle and practicality” by believing herself to be an “owner” and “manager” of the slaves. In her letter to Bess on January 2 of 1857, she writes: “I had set my mind upon a little girl” to buy as a slave.[3] Disregarding the objectification set upon the child, Lacy’s use of “set my mind upon” infers that she finally felt like she was in control of something and had the “upper hand” to a decision made in the household—a rare find in a world where women’s traditional role operated completely separate from one of “work and politics.”[4] Lacy turned a trivial pursuit for a new worker in their household into an “almost universal dilemma,”[5] as ‘ordering’ these slaves served to be the one way in which she, as a slave-holder’s wife could exert her power where typically she would be “alienated from [her] own society,” trapped in a bubble within their household.[6] This dehumanizing treatment to those “racial[ly] inferior” of the white bourgeois class revealed in the language of Lacy’s writing served as a “feminine guise” to mask the desperation a woman felt to hold a place in society as a slave-holder’s wife.[7]

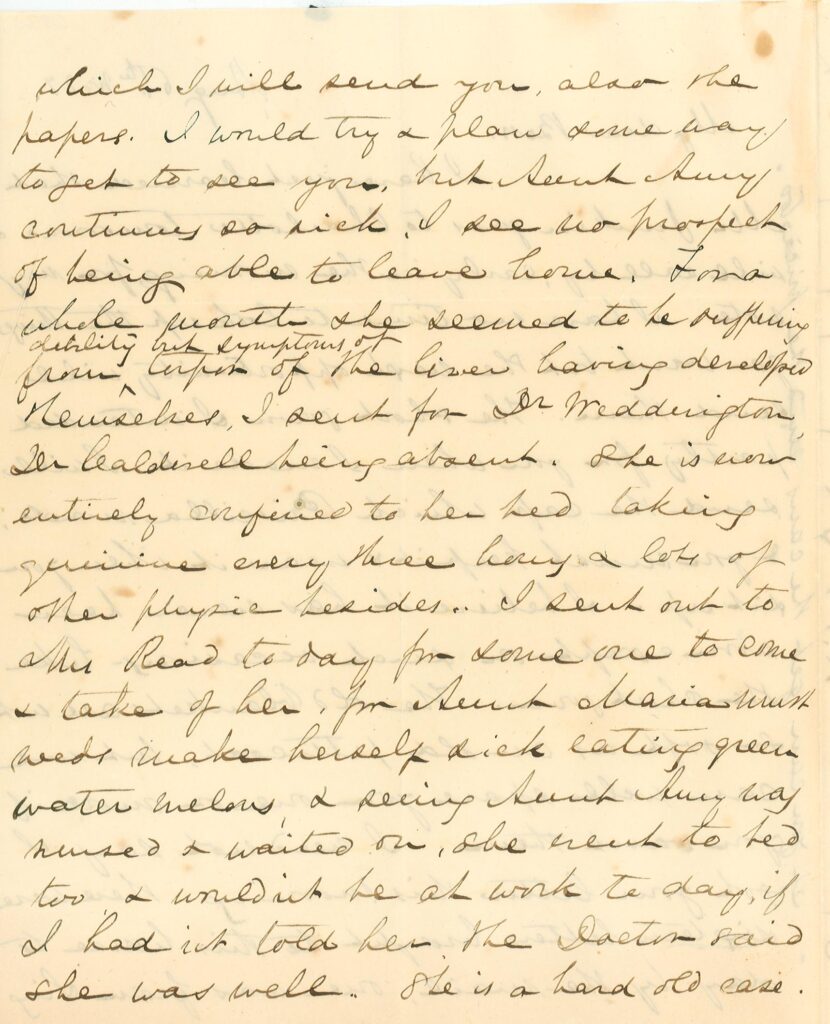

Mary Lacy’s letters not only reveal the atrocious behavior of the slave-holding women at the time towards the slaves which occurred nearly every day in the 1860s in North Carolina, but they also have a strong tie to Davidson College which are unbreakable. As wife to a previous President at Davidson, her baneful acts are coincidentally elusive, as they are not actively publicized by the college. This contradicts the slogan embodied by the college, “#DAVIDSONTRUE”, one which according to the college marketing website is defined by “deep sincerity, unquestioned integrity, and fundamental decency.”[8] If truth at the college is such an “elusive” concept, then why must students excavate to uncover the racist actions committed by the former President’s family?[9] Mary Lacy’s letters serve as an important reminder that we, as Davidson students, bound by the Honor Code which serves as one of the defining principles at the college, are entitled to this information and that it is imperative, that no matter which class we are enrolled in, we learn the truth about the college’s history.

[1] Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, “Black and White Women of the Old South.” Within the Plantation Household (The University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 46.

[2] Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Williamsburg, Virginia: University of North Carolina Press, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1980), 152-153.

[3] Carlina Green et. al, “January 2, 1857.” Mary Lacy Letters (Davidson: WordPress, 2017).

[4] Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 2009), 113; Laura F. Edwards, “At the Threshold of the Plantation Household: Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Southern Women’s History.” The Mississippi Quarterly 65, no. 4 (2012): 578.

[5] Jones, 115

[6] Fox-Genovese, 53.

[7] Fox-Genovese, 50; Fox-Genovese, 51.

[8] Davidson College, “#DAVIDSONTRUE” (Davidson: Davidson College, 2020), https://www.davidson.edu/about/davidsontrue.

[9] Ibid.

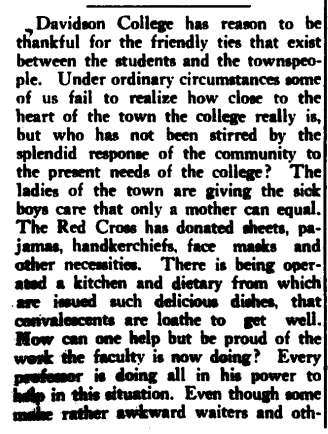

This is the third post in a three-part series about Mary Lacy, the wife of Drury Lacy, the third President of Davidson College. In our collection, we are fortunate to retain a collection of Lacy Family Papers, which includes correspondence from Mary Lacy to her step-daughter Bess. In Spring 2017, Dr. Rose Stremlau’s History 306: “Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” class transcribed, annotated, and analyzed these letters. Their work can be found on this website. To view digitized items from the Lacy Family Papers, please explore Digital Davidson, our platform to view born-digital and digitized versions of archival materials, special collections, and college scholarship.