No cookies this week but a little more on researching aspects of women’s lives–this time looking for Jane Austen in the college’s curriculum. Given that full coeducation came late to Davidson (unofficially co-eds have been on the scene since the 1850s, officially since the 1970s ), it would not be surprising to find women writers, including Austen, slow to appear on class reading lists.

A little searching turned up that should Davidson students in 1888 have made it to Chapter 6 “Our First Great Novelists” in their assigned textbook Nicoll’s Landmarks of English Literature, they would have encountered some faint praise of her work. Naming her “a greater novelist” than either Fanny Burney or Miss Edgeworth, Nicoll brief summary of her work concludes “In her chosen walk of fiction, truthful pictures of the 0rdinary, middle-class society we see around us, Miss Austen has not equal; and the extent to which she succeeds in interesting us in her annals of humdrum, commonplace English life is the highest tribute to her genius.”

Title page for English textbook used in 1880s and 1890s.

English literature first invaded the classical curriculum of Davidson in the 1870s; John Milton and Francis Bacon opened the way to survey classes for prose and poetry; Shakespeare soon earned classes of his own. By the 1930s, the English department had expanded sufficiently in number of faculty and course listings to provide students with deeper encounters with novelists.

1929 Catalog listing announcing the new course The English Novel to Hardy.

Changing course numbers and faculty (James Purcell succeeded William Cumming), the English Novel to Hardy remained a department fixture into the 1970s. Purcell added to the number of women writers being taught with his Women in American Fiction course introduced in 1973. The course readings included both male and female writers while focusing on women as characters. Four years later, Assistant Professor Georgiana Ziegler offered a course focusing on women as writers.

1977 course description returning Austen to the classroom.

The course description identifying the instructor as “Miss Ziegler” was not a slight but a reflection of the era when all faculty were listed as Mr. or Miss. A decade later, Ziegler’s replacement in the course was Ms. Mills, who kept women writers before students into the 1990s.

Ziegler and students in an outdoor class session – perhaps discussing the English countryside of Austen

The British Novel returned to the curriculum by 2000 and in 2001-02 the list of advanced English seminars included ENG 472 Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy: Sex, Politics and the Novel.

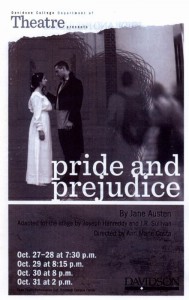

In 2010, Austen jumped from the confines of English into Theatre with a production of Pride and Prejudice.

Playbill for fall 2010 production

This search for Austen was not exhaustive. Despite the best efforts of archivists to document curriculum, there are limitations. At Davidson, we have a full run of catalogs which provide listings of course titles and brief descriptions but very few syllabi before 1994. If the course listing doesn’t name an author, we can’t know for certain what was taught. Fortunately for this search, our catalogs are online and searchable. And another library has done the work of digitizing Nicoll’s Landmarks, giving us a way to look at what the students of the era saw.

We might have a notion of what students thought about Austen but the literary magazines of the day are not quite as accessible yet. If the Davidson Monthly has articles on Austen, it will take a longer and slow search to find them!

Speak Your Mind