Mandy Muise is a sophomore currently majoring in anthropology with an intended minor in Latin American studies. On campus, they work as the anthropology consultant for the Writing Center and are currently interning with the Antiquities Coalition.

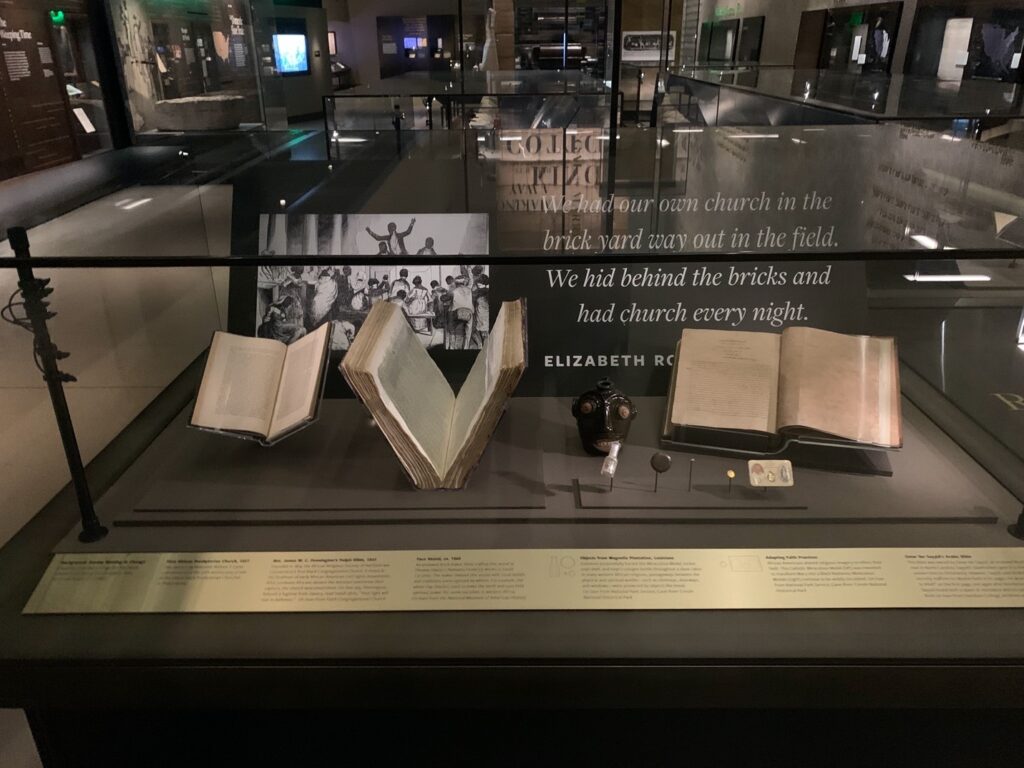

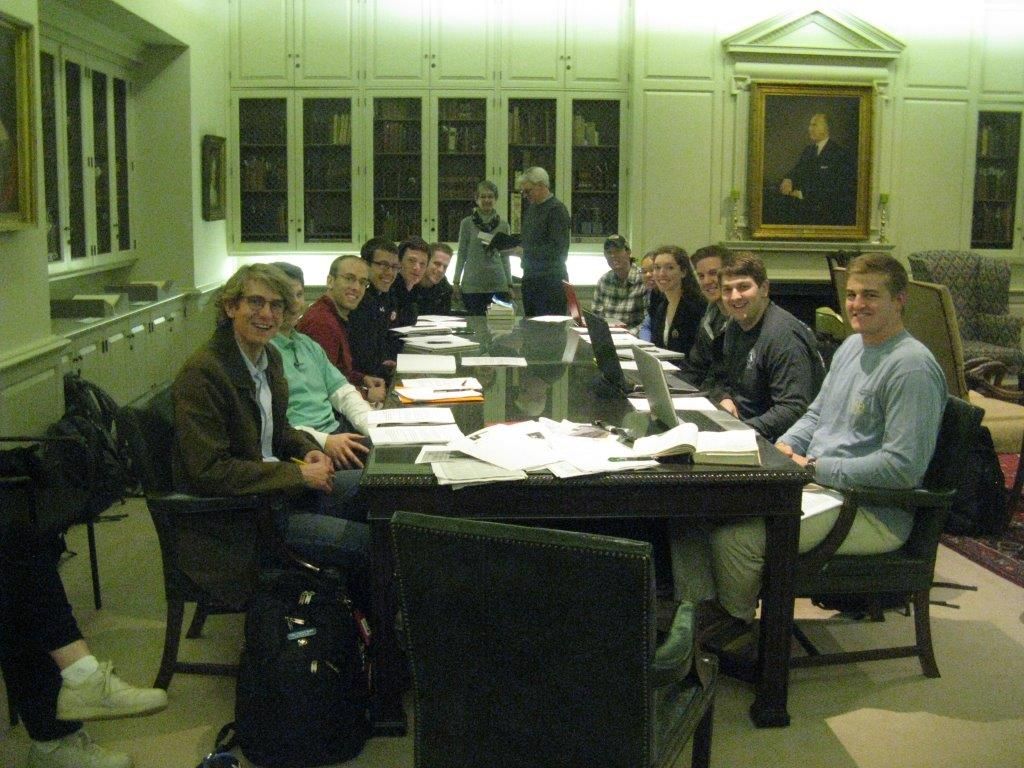

As part of the Ethical Archaeological Research seminar, I began my work on a project called Historical and Community Archaeology: The Enslaved People of Beaver Dam (henceforth referred to as the Beaver Dam project) as a bit of an archaeological outsider – and to a degree, I remain one. Although I am an anthropology major, my concentration has always been on the cultural side; as a result, I found myself outside of my comfort zone in an archaeology seminar. It took me quite some time to find my place in a project defined by archaeological perspectives and jargon I had not previously encountered. I found myself lost as to what we could gain from pottery sherds and confused about what possible implications historical archaeology could have upon a community. Archaeology is built upon colonial ways of knowing, and prior to becoming introduced to Community Based Participatory Research in archaeology (CBPR, discussed below), I saw zero potential for an archaeology that actively served a community.

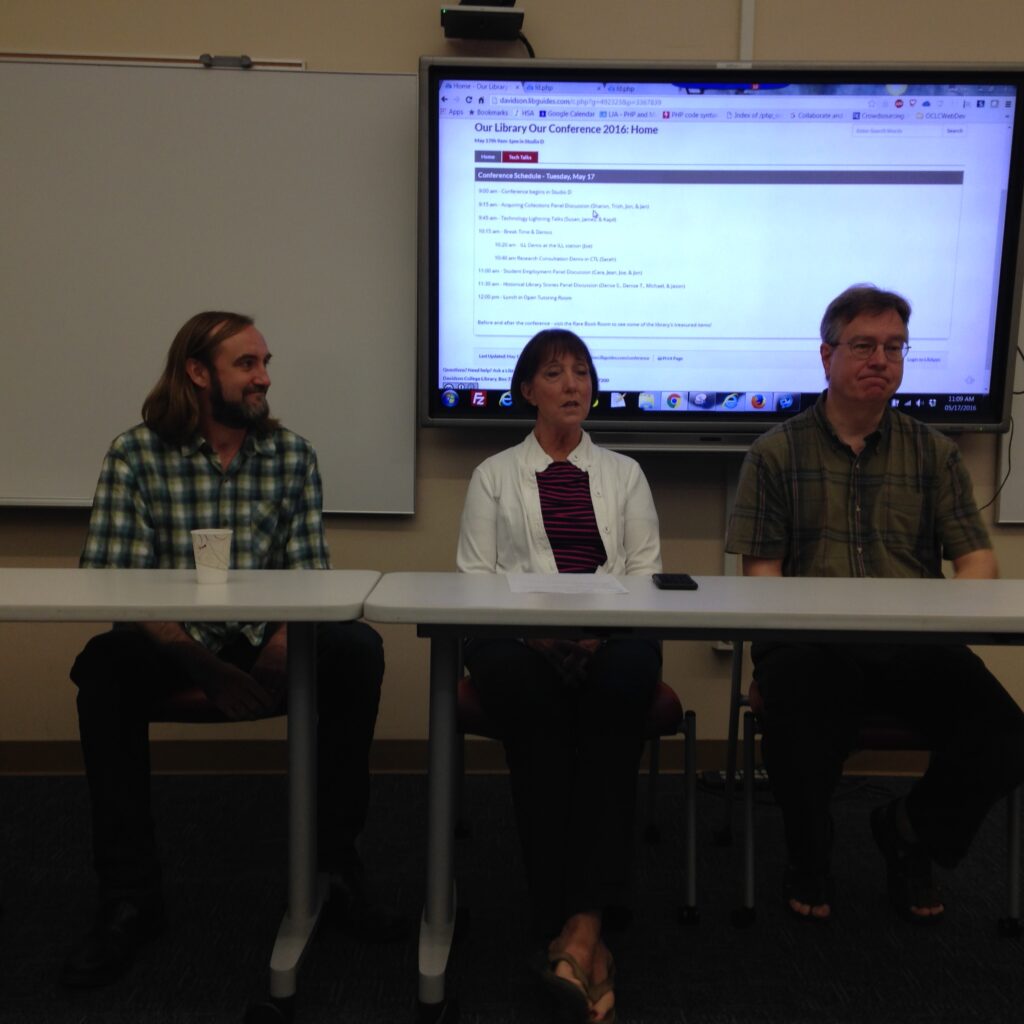

In most simplistic terms, CBPR is an archaeology that advocates a movement away from scholarship “on and for” and toward archaeological practice “by and with” a community. It was best defined by Sonya Atalay (2012), an archaeologist specializing in Indigenous archaeology. CBPR creates a methodology that seeks to decolonize archaeological practice to create a more equitable form of research that is mutually beneficial to the community and to academics alike through the democratization of the knowledge production process.

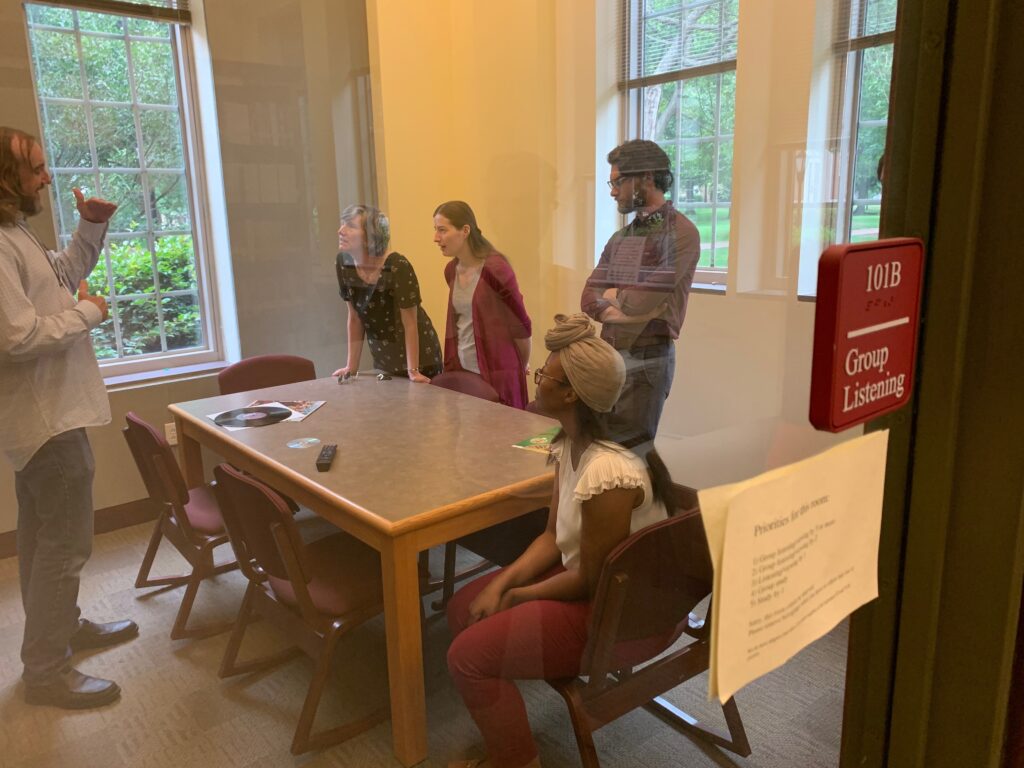

My role in this project ultimately consisted of contacting prominent members of the community for information, advice, and to build connections for eventual in-person activities. In doing this, I’ve developed an appreciation of the difficulty of engaging in CBPR with a community that has not expressed an interest in archaeology. As a result of these challenges, our project has not consistently been able to uphold the objectives and ideals of CBPR. As it stands, our project is not community-engaged beyond the intentions of our group, as our accomplishments thus far have been without the support or desire of the community.

How can we understand this project to be an anti-racist and ethical endeavor in lieu of community engagement? Rather than seeing the project as aligning with older archaeological practices, it is critical to recognize our project at Beaver Dam as still in its initial stages. We have hardly stepped back from the chalkboard, despite the semester coming to a close. What we have successfully done is set the stage for CBPR, creating space in which this project can come to fruition. Our project has been designed with endless flexibility in hopes of community engagement – research questions and ideas are open to adjustments, and excavation can and will wait for the community. I see the Beaver Dam project as full of potential, founded upon ethical and anti-racist intentions – assuming the project continues its trajectory of community engagement, I have confidence that this project will continue to emphasize service to the community through mutually-beneficial scholarship.

Bibliography

Atalay, Sonya

2012 Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities. University of California Press, Berkeley.