After multiple class sessions introducing our archival and manuscript collections and oral history best practices, students in Dr. Nneka Dennie’s Spring 2019 AFR 329: Women & Slavery in the Black Atlantic course produced a documentary using oral histories created throughout the semester. These materials will be donated to the Archives.

In addition to this main project, students were tasked with identifying primary sources from local archives, historic sites, and/or repositories that shed light on the lived experiences of enslaved women or women enslavers. The following series of blog posts are authored by these students upon the completion of this archival research process and serve as reflective pieces.

Thank you for your submissions-and a wonderful semester of fruitful collaborations!

“Education, Freedom and the Archives”

written by Lucy Walton

Even today, education is seen as a tool to upward-mobility, and often regarded as (though proven to not be) a great equalizer of people. This view of education is not new, though perceptions of who should have access to education have greatly shifted since the Civil Rights Movement. Although education in the United States remains inequitable today, one would be hard-pressed to find someone who was willing to say that every child did not have the right to go to school. However, in pre-emancipation United States the saying “knowledge is power” instilled a fear in enslavers that education would inevitably lead to enslaved persons’ revolts, runaways and manumissions. In the south, enslaved black people faced intense punishment for seeking education and laws explicitly banned literacy.

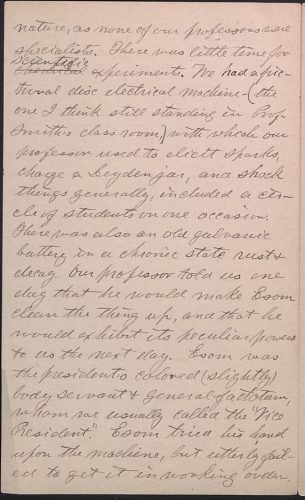

The interview of Lizzie Baker, a post-emancipation freed woman, touches a bit on this fear of education enslavers had. Baker herself was very young when emancipation happened, but she recounts stories that her parents told her about their enslavers specifically methods they used to oppress, dehumanize and punish their enslaved people. In the interview she discusses how hunters would try to catch enslaved people by tying ropes across roads to trip them. Then she directly moves into saying “marster and missus did not ‘low [allow] slaves to have a book in deir house. If dey caught a slave wid a book in dey house dey whipped ‘em. Dey were keerful not to let em’ learn reading or writing.” After this she changes topics again to talk about the selling of her siblings. Both the content, and the placement of this quote are telling.

First, it shows that enslavers made conscious efforts to keep enslaved people from learning valuable skills, indicating they were afraid of the consequences this would lead to. Second, as the story sits in between one about catching fugitives and one about family separation it connects the denial of education to other horrible forms of dehumanization that enslavers enacted upon enslaved. That education denial is placed on the same level as hunting, and family separate proves the importance of literacy and knowledge both to enslavers and enslaved.

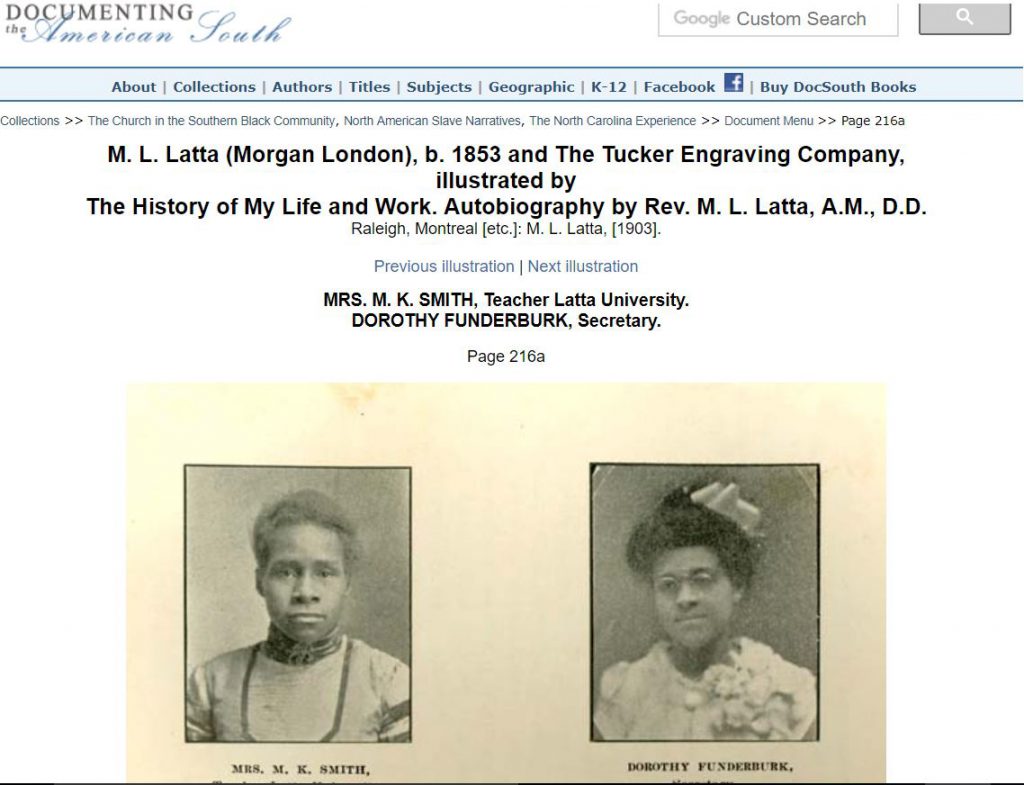

Other sources in the archives show the empowerment of education, particularly for women. Many sources about freed black people in the area are connected to Latta University, a school set up by Reverend Morgan Latta for freed black people to get education. Rev. Latta’s choice to set up a school displays his belief (shared by many) that education would be the gateway to opportunity for those manumitted. Although black women were doubly oppessed by their race and gender, Latta’s school provided such opportunity for women who could become students, or even teachers.

One photograph found in The Archive for Documenting the American South shows Mrs. M. K. Smith and Dorothy Funderburk. Smith is labeled as a teacher, and Funderburk as a secretary. Both are wearing fine clothing, and the fact that they are photographed shows the importance of their position within their community. Historically, teachers and those connected to schools would be regarded as more upper class and would be highly respected for their role in passing on important skills like reading and writing. Investigating the role of Latta University and its connection to Mecklenburg county could be an important line of further research.

These sources and more within the archives, accessible to Davidson students, prove the power of education for enslaved people, both through the respect given to those involved in it, and by the lengths enslavers would go to stop it. As an American historian I have studied the progression of educational equality in the United States from the creation (and continued importance) of HBCUs to the desegregation of schools in the decades after Brown v. Board (yes, it did take decades). That push began early in U.S history with the actions black people, both enslaved and freed, made to gain literacy and other forms of learning. This serves as a reminder that education, even within the academia, can be used as a tool for personal resistance.