In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Today the Chambers bell alerts students and professors to begin and end class. However, in Davidson’s early years, the Davidson College Presbyterian Church’s bell, like Chambers’ bell now, symbolically dictated every aspect of Davidson students’ lives. As an institution that determined social morals and discipline, the Presbyterian Church not only told students when to go to church, but what to study, and how to live.

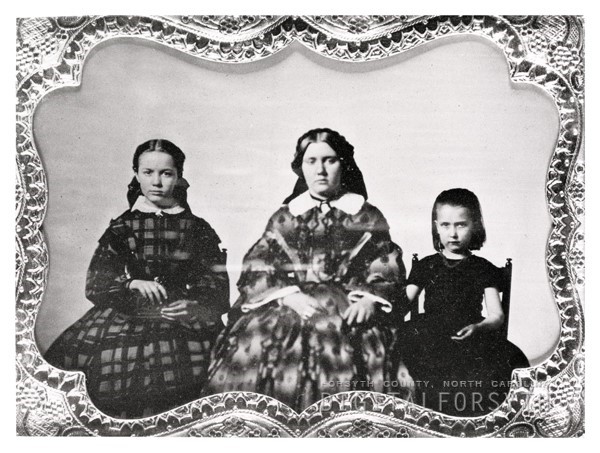

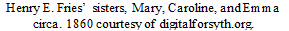

Henry E. Fries, a student at the college from 1874-1876, wrote two separate letters to his sister and mother on April 2nd, 1876. In both letters, Fries discusses the significant role the church played in the organization of his day-to-day life. He apologized for his delay in response to his sister by blaming the church: “I have as much, if not more, to do on Sunday than any other time.”1 On this Sunday, Fries had to “attend church three times” and prepare for bible study.2 The Presbyterian Church also instilled social morals into Fries who decided to forgo dancing, which the church saw as an anti-religious encouragement of perverse sexualities.3 He writes to his mother: “I can now see the evil in some of my past pleasures, and as I spoke to you about dancing, you will see that at last, I have conquered my love for it.”4

Fries’ letter provides insight to the religious fabric of the United States South. Religion generally provided a social web and community-situated framework for morality and actions. Presbyterianism consumed most of Davidson students’ life at the time. Sunday, Fries’ supposed day of rest, was actually filled with worship and community building within the college and the town.

“Worldly pleasures,” now often associated with typical college life, like dancing, drinking, pre-marital sex, profanity, and theatre were considered violations of Presbyterian morals. These actions could be swiftly punished by admonishment or, in severe cases, excommunication by the church, and, as church membership was required by the college, expulsion.5 Therefore, when Fries ended his letter to his mother quickly stating: “I believe this is about all I have today, the church bell has already rung, so I must close,” he truly meant it.6 From what students read, to where they went, and when they had to be there, the Presbyterian Church, and its bell, determined all aspects of student life.

Works Cited:

Henry E. Fries, Letter to Sister, 2 April 1876, DC0029s, Henry Elias Fries, 1857-1927 (1878) Papers, Davidson College Archives and Special Collections, Davidson, N.C.

Jane R. Jenkins, “Social Dance in North Carolina Before the Twentieth Century: An Overview,” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1978), ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (7824302).

W.D., Blanks, “Corrective Church Discipline in the Presbyterian Churches of the Nineteenth Century South,” Journal of Presbyterian History Vol. 44, No. 2 (June 1996): 99.

Henry E. Fries, Letter to Mom, 2 April 1876, DC0029s, Henry Elias Fries, 1857-1927 (1878) Papers, Davidson College Archives and Special Collections, Davidson, N.C.

Speak Your Mind