In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Marshall Bursis is a senior political science major and history minor. He is from Lake Ariel, Pennsylvania.

Davidson College is a fundamentally Southern institution. Its antebellum founding and setting within the former Confederacy intimately connect the college and the town to the social context of Southern life in the 19th century. This may seem like a truism, but it is an essential acknowledgement. If we hope to more fully understand the history of the school and the town, we must interrogate the parts of the Southern experience that we may wish to overlook—like the systems of slavery and Jim Crow. Included in this more complete history is how the town reconciled with the realities of Reconstruction.

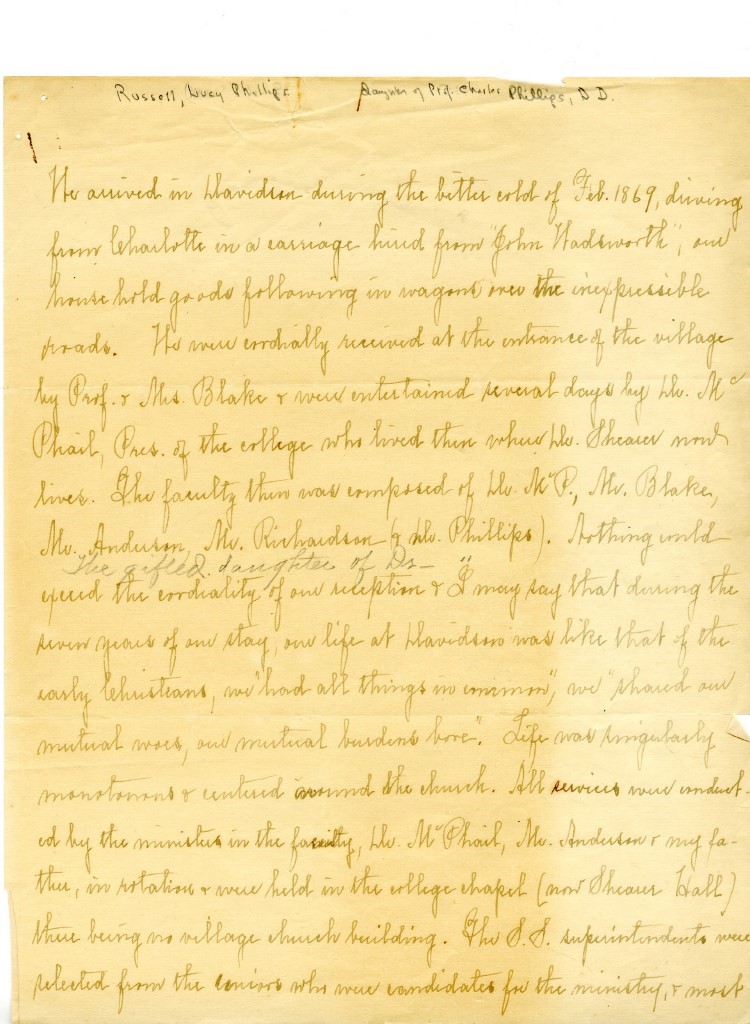

The writings of Lucy Phillips Russell, daughter of professor Charles Phillips, provide a description, albeit incomplete, of Davidson College during Reconstruction and the childhood of the local elite. Lucy Phillips moved to Davidson in 1869, where she lived until 1875. Her recollection of her childhood at Davidson includes stories about the workings of the college and the town and a subtle assessment of her own experience as a young girl navigating the norms of the post-war South.

Her account makes clear that religion dominated the lives of the students and those in the town. She describes religion and the church as “the shining element of the college and village life.” Russell characterizes her childhood in Davidson as “singularly monotonous and centered around the church.” Furthermore, her recollection of a single-mother living in the town is especially compelling. The exact source of the estrangement between the mother and father is unclear, but she implies that he abandoned her. Writing from 1920, Russell decries the “medieval times” that trapped this woman and made her miserable. “A modern woman” she writes, “would fly to a divorce court and make a joke of the whole situation.” It is clear that divorce, even for legitimate reasons like prolonged abandonment, were socially unacceptable in the Davidson of the 1870s. Russell’s characterization of this woman’s struggle indicates the significant transformation in marriage norms over less than fifty years.

However, despite the source’s usefulness at examining the religiosity of the community and the town generally, it only tacitly acknowledges the broader context of Reconstruction. Russell remembers that during her childhood “every body was poor, because the whole South was.” Russell, however, makes no recognition of the source of this widespread condition—the destruction of war and the emancipation of slaves that previously provided incalculable amounts of free labor.

From this believed universal poverty, Russell perceived her community as radically egalitarian, where “every body lived in charity with every body else, nurse each other in sickness, wept with each other in times of sorrow and death, enjoyed with each other when fortune smiled.” It is natural that Russell would hold nostalgia about her childhood, but her conception of an idyllic Davidson ignores the tension that remained in the South between the white community and newly freed blacks. Russell’s failure to adequately reckon with this troubled history mirrors our modern struggles with the problematic portions of our past.

Bibliography:

Russell, Lucy Phillips. Letter, “Lucy P. Russell 1920 Letter,” 1920. http://libraries.davidson.edu/archives/digital-collections/lucy-p-russell-letter-1920#Works.

Speak Your Mind