In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

My name is Elsa Conklin and I am a sophomore History and Hispanic Studies major from outside of Seattle, Washington.

Many, many years ago, Davidson College held a strict and vastly different policy that likely irked the students: alcohol was banned throughout the entire campus. This caused conflict throughout the years, yet was a multifaceted issue that gave way to other issues around the area. Alcohol was something that intersected race, student life, and also the lives of the women of Davidson.

Mary Lacy was a woman of the town of Davidson in the 19th century, the wife of Rev. Drury Lacy who served as president of Davidson College from 1855 until 1860. A faithful step-mother to her formerly widowed husband’s six children, she wrote several letters to her step-daughter Elizabeth, casually referred to as Bess. She confided in Bess, and her letters are a window into the world surrounding Davidson College from the year 1856 to 1859. Her unique perspective provides a glimpse into what life was like in Davidson at this time, as she discusses everything from health and childbearing to her slaves to friendships and familial relationships.

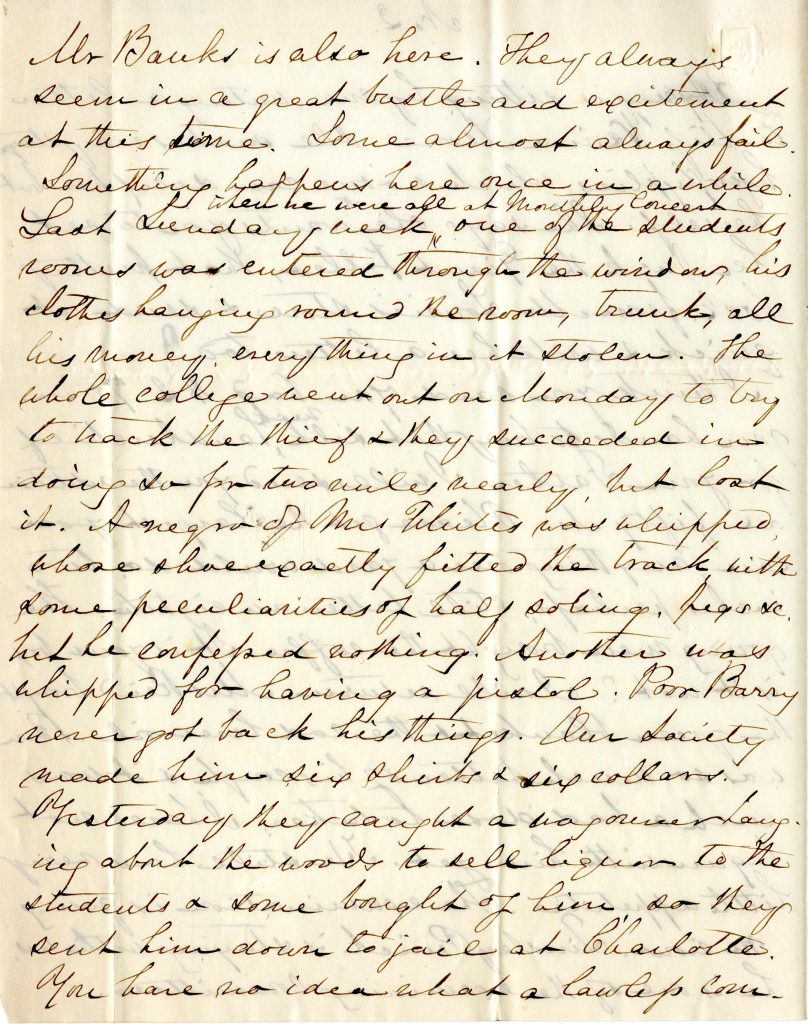

In her letter to Bess in February of 1859, Mary relates a conflict that occured in Davidson recently that touches upon multiple issues. She writes, “Yesterday they caught a wagoner hanging about the woods to sell liquor to the students & some bought of him, so they sent him down to jail at Charlotte.”1 Continuing this thought and giving the modern reader insight as to the relations between enslaved persons and white women in this time, she details, “You have no idea what a lawless community this is… We are much in hopes these two events will strike terror into the negroes & the whiskey sellers”.2

Though the wagoner in this situation appears to be a free man, she brings “negroes” into the situation and holds them to the same accusations. This connection indicates a particular kind of thought towards enslaved people from their white mistresses at this time, a mentality reflected in Thavolia Glymph’s “Women in Slavery: The Gender of Violence”. Mistresses were often the ones designated within the household to punish their slaves, and it was usually a job devoid of empathy and respect for the enslaved as fully human. Though we don’t have specific documents detailing enslaved persons’ involvement in the trading of liquor, Mary’s letter provides an interesting insight as to how assumptions such as these created intersections between alcohol, enslaved persons, and women in the town and college of Davidson. Perhaps slaves were selling alcohol to students in the woods, but without any firm evidence, we can’t say this for certain.

Bibliography:

Davidson College HIS 306 Spring 2017. “The Mary Lacy Letters.” The Mary Lacy Letters. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/.

Mary Lacy to Elizabeth Lacy, February 1859, in “The Mary Lacy Letters”, https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/.

Glymph, Thavolia. “Women in Slavery: The Gender of Violence.” Out of the House of Bondage, n.d., 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511812491.002.

Speak Your Mind