This week’s post is written by Dr. Anelise Hanson Shrout, the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Studies.

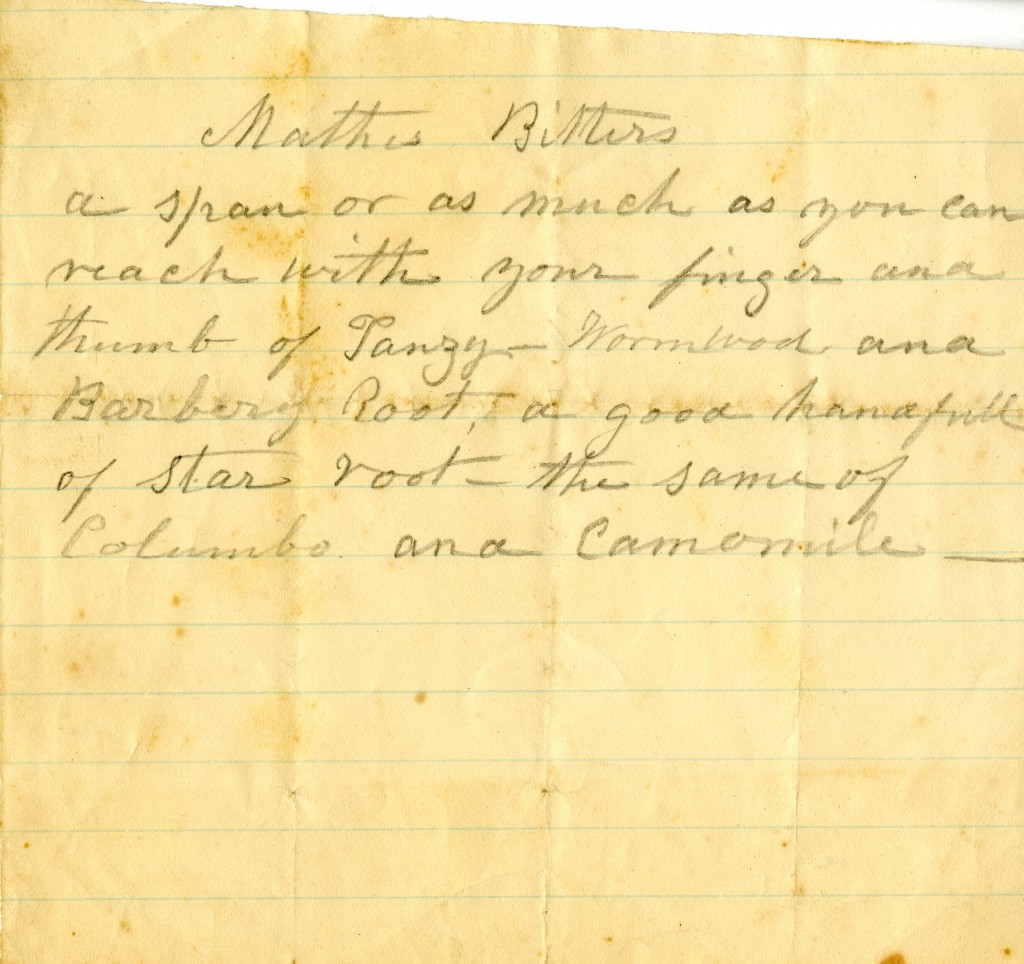

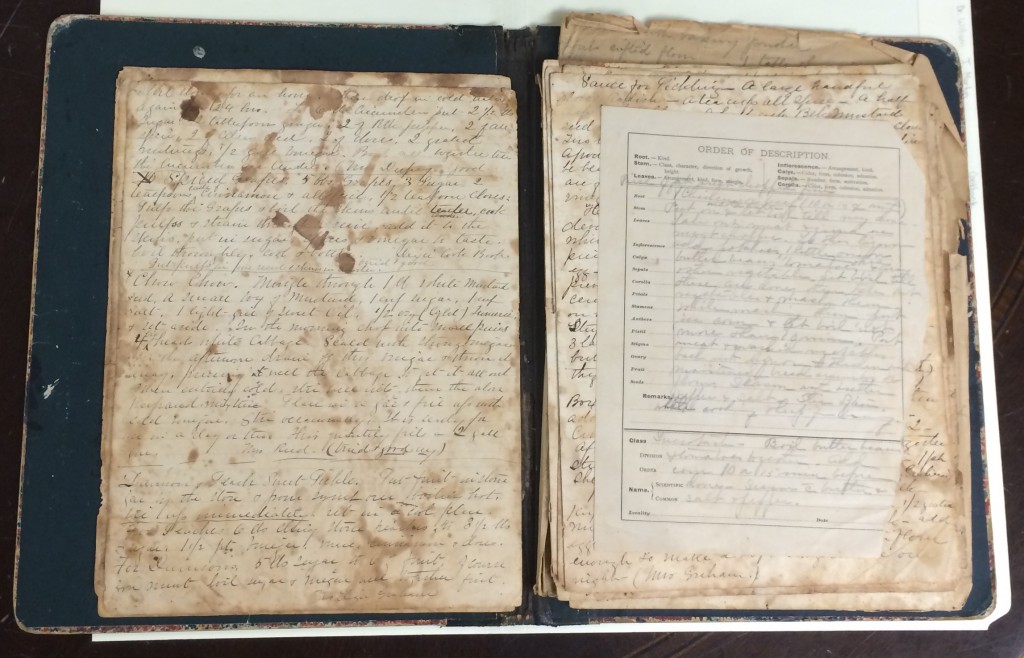

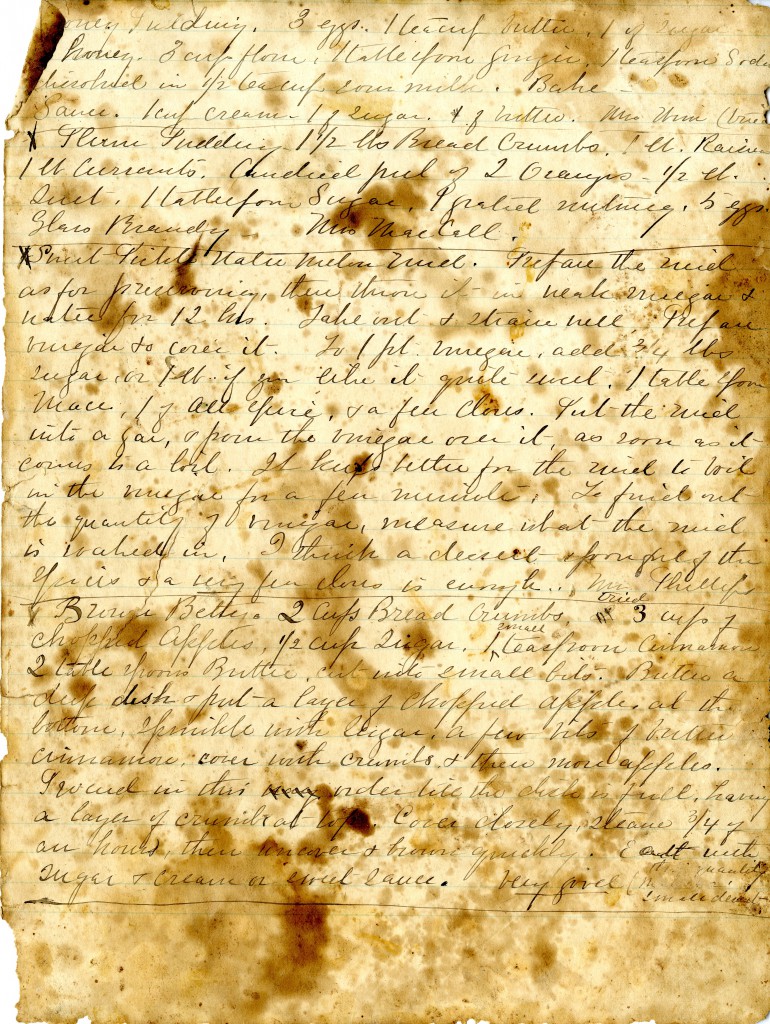

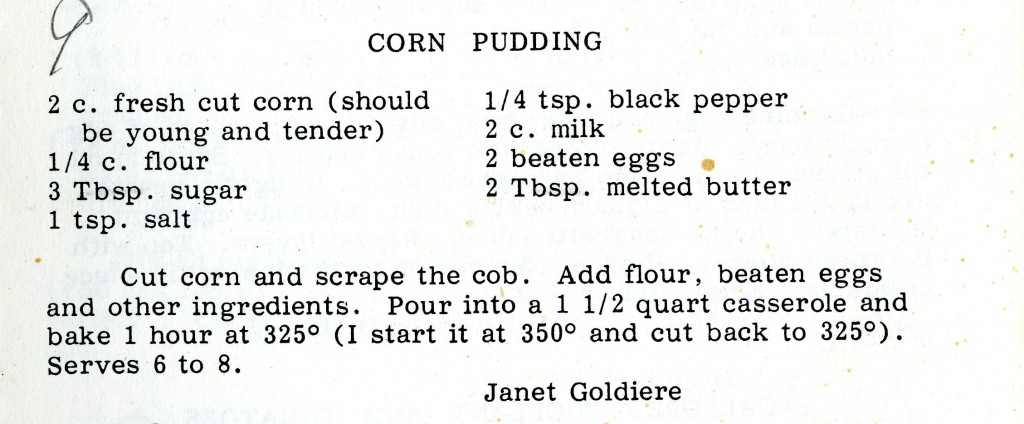

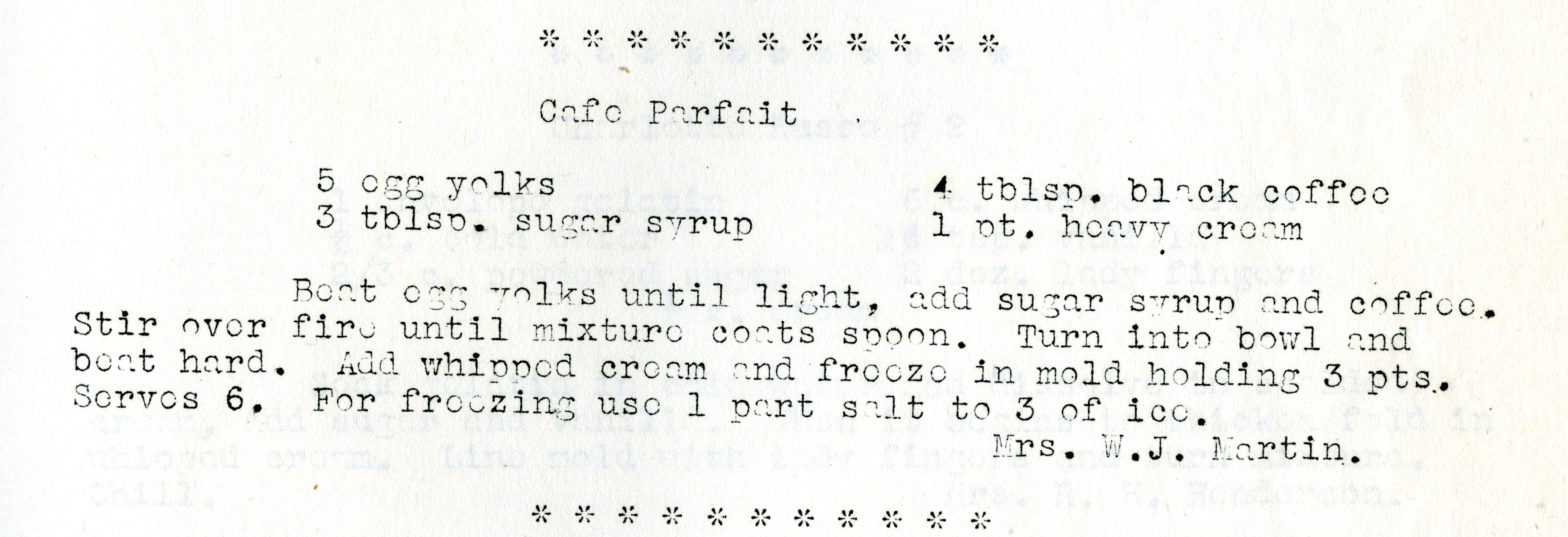

Lewis Bell came to Davidson College in 1865 and graduated in 1870. Though he was a student during the Reconstruction Era, it is likely that most of his college experiences were mundane. He was a member of the Eumenean Literary Society. Among his papers held in the college archive is a donation request from the society from the year after he graduated. Like many Davidson students, he also seems to have been concerned with his grades. His papers also contain a list of Davidson College students and their grade averages from 1865 to 1868. We know little more about Bell’s time at Davidson, except that he also seemed to have an interest in spirituous liquors. A final item in the John Lewis Bell collection is a well-used recipe for “Mother’s Bitters,” which was comprised of “tanzy, Wormwood and Barbary Root, a good handful of Star root, the same of Columbo and Chamomile.”

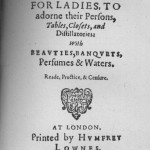

Bitters are an aromatic flavoring agent, made by infusing roots, bark, fruit peels, herbs, flowers and botanicals in alcohol. These spirits are used in fancy craft cocktails today, but were historically put to more medicinal purposes. In his history of bitters, Brad Thomas Parsons situates these infused spirits in a long history of “a cure for whatever ailed you” – beginning with Stroughton Bitters, which were patented in 1712, and which contained “1/2 drachm cochineal, 1 pint alcohol, ½ canella bark, ½ ounce cardamoms” and were made by being left to “stand eight days; draw it off clear and bottle it. For medicinal purposes use French Brandy instead of alcohol.” (From Monzert, Leonard. The Independent Liquorist: Or, The Art of Manufacturing and Preparing All Kinds of Cordials, Syrups, Bitters, Wines … John F. Trow & Company, 1866.)

Why would Bell have kept a recipe for bitters amongst his Davidson paraphernalia? He might have been keen on bitters for recreational imbibing purposes. Americans were certainly interested in mixed drinks during the years that Bell attended Davidson, and cocktails had a long history. People in England in the eighteenth century were known to mix patent bitters with brandy, and by 1806 the word “cocktail” had developed to mean “a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water and bitters.” However, in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, Davidson College was very concerned with limiting students’ access to alcohol. It prohibited the sale of alcohol in college-owned properties, and brought suit against stores that sold spirits to undergraduates. Perhaps Bell was unable to buy bitters for cocktails in the town, and had to resort to making them himself.

Bell might equally have been using “Mother’s Bitters” as a patent medicine. In the late nineteenth century bitters were sold as a remedy for all manner of ills. In 1866, the American Agriculturalist noted that bitters could aid in “weak digestion or a debilitated state of the system, if properly taken under medical advice.” Similarly, Rowney in Boston (1892) spoke to the benefits of “mother’s bitters, made of dandelion root, and such wholesome things.” In her study of alcohol and botanicals, Amy Stewart writes that from the eighteenth-century forward, people “realized that adding wormwood to wine and other distilled spirits actually improved the flavor or at least help disguise the stench of crude, poorly made alcohol.” Chamomile, barberry root and tansy also have practical purposes – all work as anti-inflammatories, and chamomile additionally works as a sedative. The combination of herbs in “Mother’s Bitters” consequently seem to have been medically beneficial. Perhaps Bell was in need of an anti-inflammatory, or means of calming an upset stomach. There were several stores on Main Street in the 1870s that might have sold bitters, but the college’s prohibition against the sale of alcohol might just as well have prevented Bell from purchasing them in town.

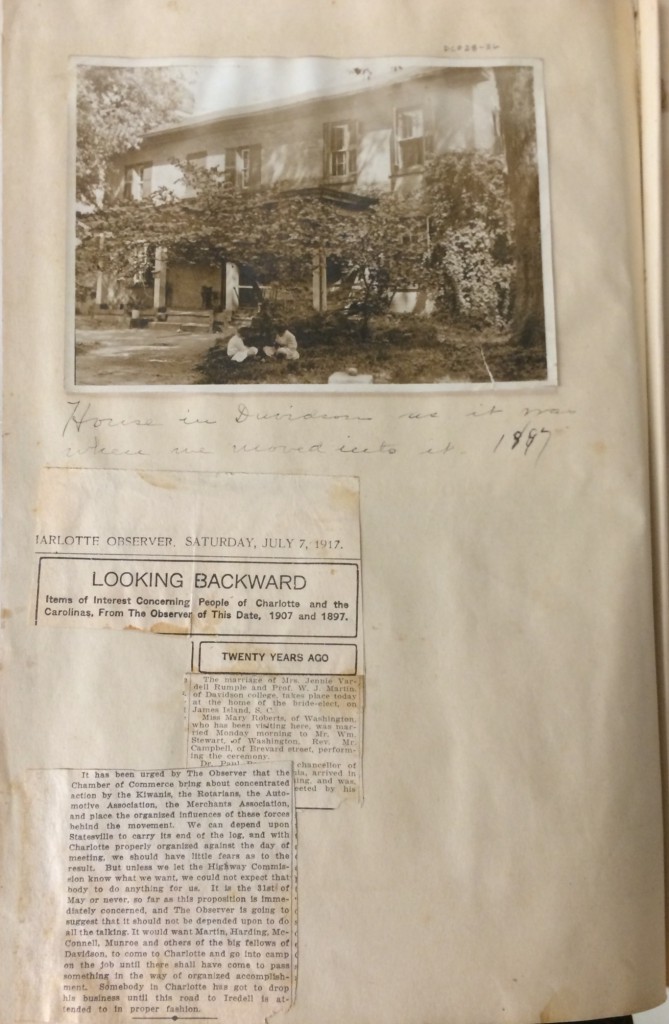

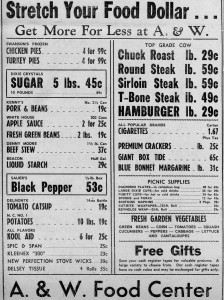

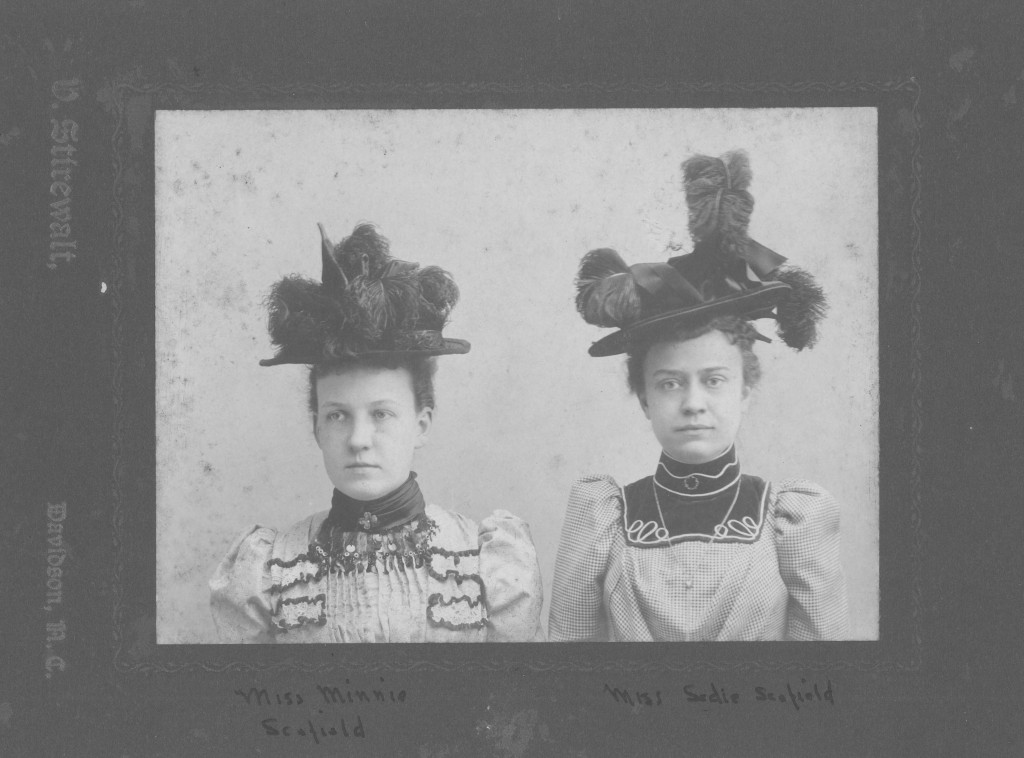

The Scofield Store was one among a few stores that might have sold bitters on Davidson’s Main Street.

So, while he might have been collecting recipes in order engage in an illicit cocktail culture, Bell might also have been trying to make a well-known remedy for a “weak destitution” or “debilitated system.”

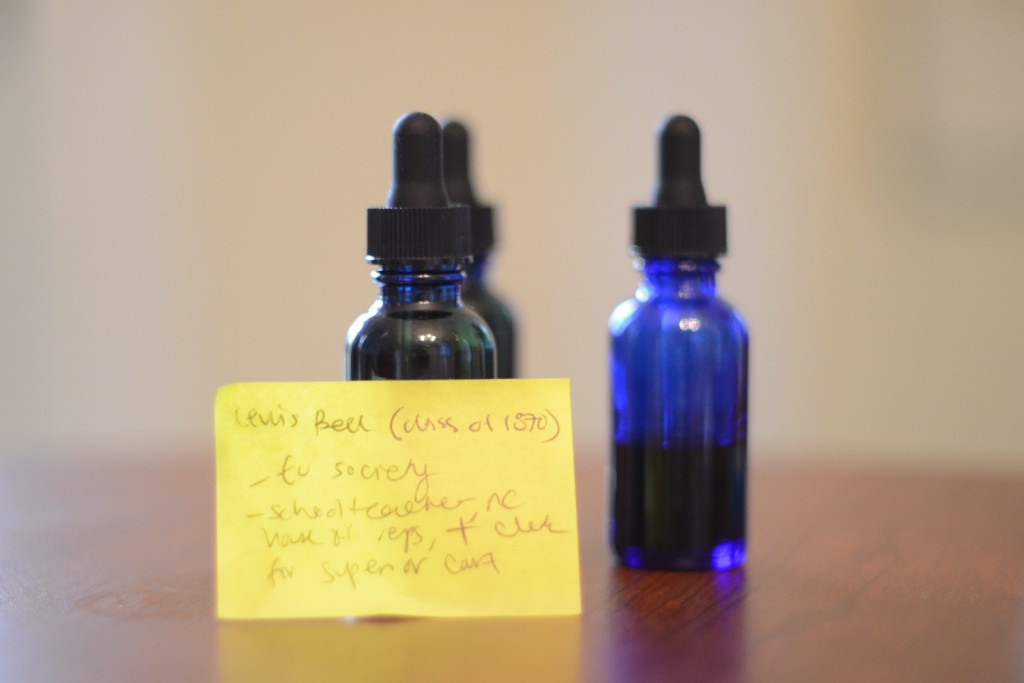

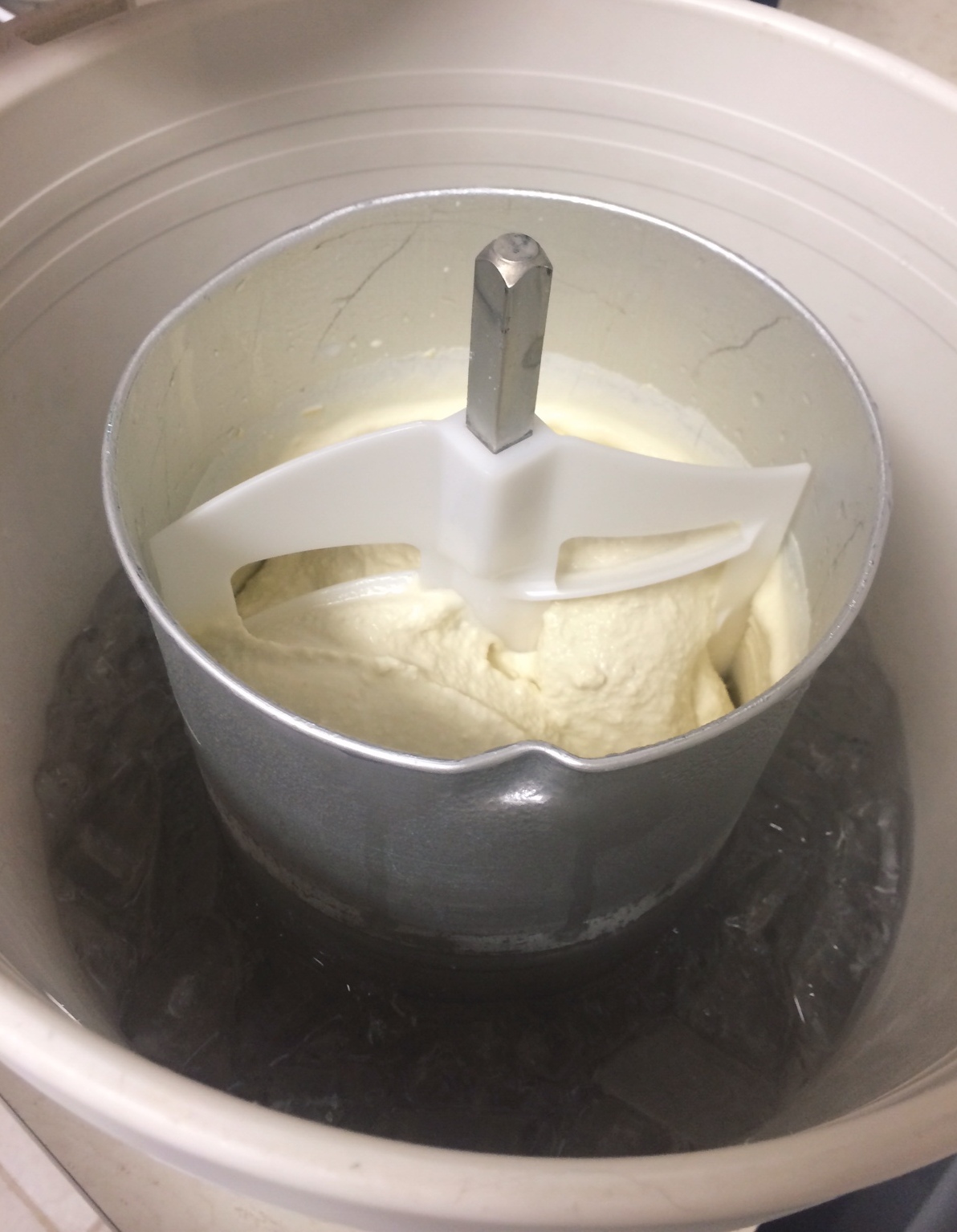

Although Bell’s use of the “Mother’s Bitters” recipe can never be known, we can still get at Bell’s experience. I recreated Bell’s recipe, using dried herbs and roots, and steeped the whole mixture in alcohol for two weeks. The resulting concoction was distinctly flavored. It didn’t taste like the bitters we use in cocktails today. Rather, it had an anise flavor, not dissimilar from pernod. This is due to the combination of wormwood (which, on its own has a menthol-like flavor), tansy (which tastes like peppermint), chamomile, barberry root, and star anise (which has a warm flavor, and was often included in absinthe along with wormwood). On a recent Monday night, a group of faculty and staff drank our “Mother’s bitters” in seltzer. We experienced it as a largely medicinal taste, and found that the smell of wormwood did indeed obscure other scents. While knowing what the bitters taste like doesn’t get us much closer to Bell’s everyday experiences of Davidson, it does help us bridge the divide between the 1870s and the present, and to imagine how a Reconstruction-era Davidson student might have imbibed.