This is part two of a two-part post.

Interestingly, this back-and-forth surrounding the black fraternity debate in 1989 was covered by a writer for the Charlotte Observer, Ricki Morrell. In her coverage, she mentions opposition within Davidson’s fraternities and dormitories against the idea of a black fraternity on campus.[7] In a short column commenting on Morrell’s piece, President of Patterson Court Council Bennett Cardwell sought to provide a clearer picture of where the Davidson student body generally was in terms of the debate. In a piece titled “Story Is One-Sided,” Cardwell identified Tom Moore as “a random senior” dissenter whose opinions did not “in any way represent those of the student body in general.”[8] Cardwell assured that the opposition to diversifying Patterson Court was much smaller than Morrell led everyone to believe; he even stated that many white students were in favor of the idea of a black fraternity.[9] Second, Cardwell rejected the notion that there were “white fraternities” at Davidson, assuring his audience that there were black members in the fraternities on campus.[10] At the time, the members in Davidson’s six fraternities comprised about sixty percent of the student body. If Cardwell was the voice of reason in this debate, then given the fact that the interest in diversifying Patterson Court persisted as time went on, why did it take until 2003 to bring any black fraternity to Davidson College?[11] Aside from later concerns of sustainability from Alpha Phi Alpha, Inc., the college still holds a large portion of that responsibility.[12] Some within the Davidson College community continued and continue to faithfully adhere to the inclusivity argument against diversification, reinforcing Davidson’s culture of color-blindness. Historically, when that argument did not work, some attempted to augment it by expressing concerns of the further fragmentation of the Davidson College community. These arguments lend themselves to the notion of minimal representation. If color-blindness has been Davidson’s modus operandi, the goal of minimal representation is Davidson’s subconscious impetus.

Alpha Kappa Alpha, Sigma Psi Chapter 2008

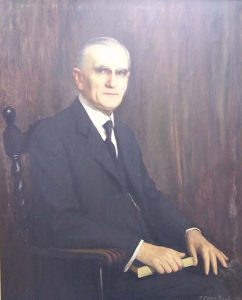

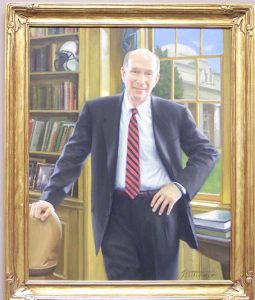

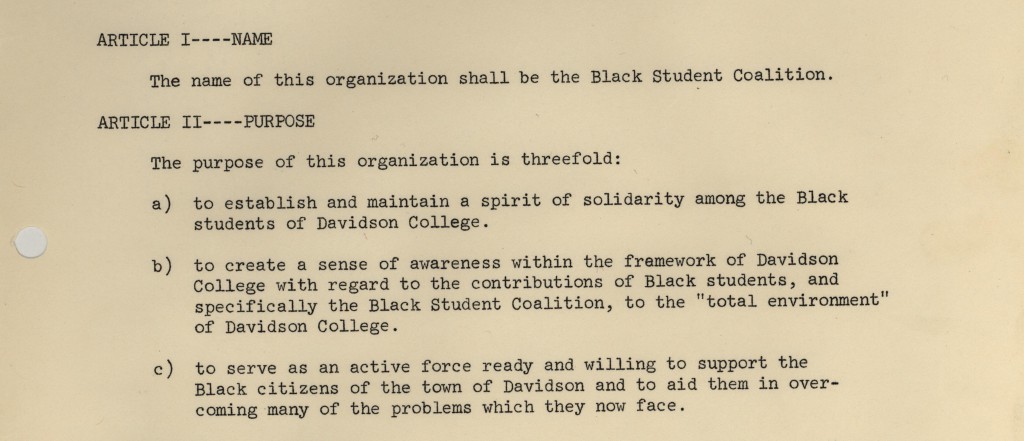

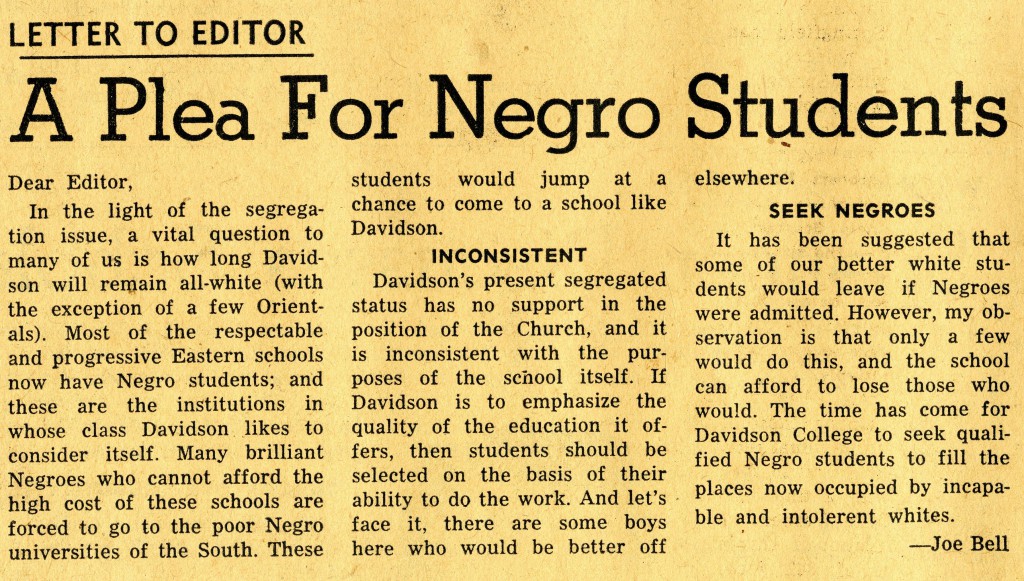

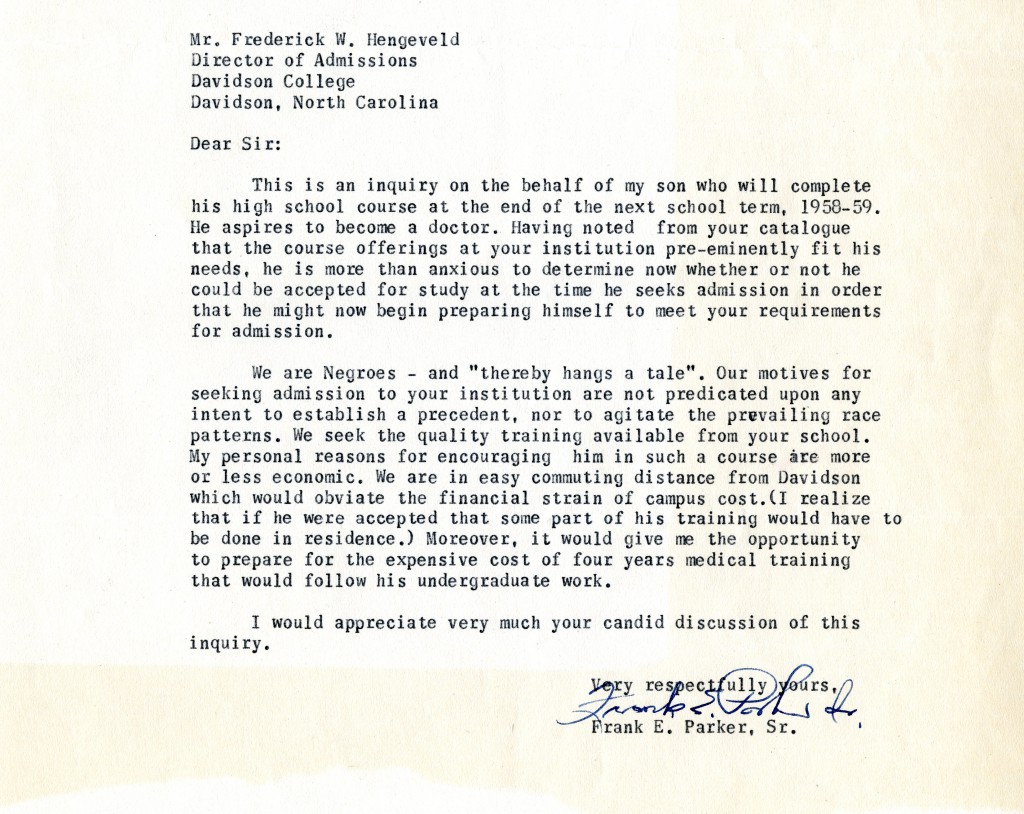

Minimal representation in this context refers to Davidson College’s tendency to strive for the bare minimum in terms of social representation so as to diversify and simultaneously be able to maintain color-blind tendencies as the institution evolves. That way, the college can comfortably fight for change and minimize social backlash on campus. The push for minimal representation is especially evident given Davidson’s decision to establish the BSC so early in the institution’s history of diversification, yet struggle with the diversification of Patterson Court for such a long time. The reluctance to establish any sorority on campus primarily due to the presence of eating houses also illuminates the desire for minimal representation. In a letter dated December 1,1997 and addressed to the President of Davidson College at the time, Robert F. Vagt, several members of the Executive Committee expressed why the college should not allow any sororities on campus. The committee stated their arguments clearly: sororities are organized around social exclusivity, eating houses are an inclusive system, and academic life would be adversely affected.[13] At this time, all of Davidson’s Patterson Court institutions were predominantly white and no sororities existed. The Executive Committee’s letter exposes the same trope evident in the 1989 black fraternity debate: the inclusivity argument, and other arguments to fall back on should the former fall through. Davidson reveals itself to be suspicious of diverse social forms and exposes its affinity for the status quo.

Alpha Kappa Alpha Insignia

A status quo is not an inherently bad thing. However, when we consider Davidson College’s constant need and desire for structural improvement, using color-blind materials is not the way to go. In fact, it is a contradiction. Color-blindness has to be removed from Davidson’s toolbox if we are to improve this institution. If Davidson directly or indirectly utilizes blindness as a tool for its enhancement, nothing is actually ameliorated, hence the status quo. Some at Davidson College still pride themselves on their color-blind ideologies, and other types of blindness as well. Color-blind arguments coupled with minimal representation kept black fraternities off of Davidson’s campus until the early to mid 2000’s. The 1989 black fraternity debate and later opposition against sororities are prime examples of the resilience color-blind ideologies have had within the Davidson College community. That is to say that Davidson College, as the institution exists now, has been compromised, just like the United States. Nevertheless, Davidson’s flaws are to be neither accepted nor celebrated unless the status quo is something we enjoy seeing.

Bibliography, Part Two

[7] Ricki Morrell. “Black Davidson Students Push For Black Fraternity,” The Charlotte Observer, Article, November 21, 1989.

[8] Bennett S. Cardwell, “The Story Is One-Sided,” 1989.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ricki Morrell. “Black Davidson Students Push For Black Fraternity,” November 21, 1989.

[12] Lincoln Davidson, “Alpha Phi Alpha marks 10 years at Davidson College,” November 3, 2013.

[13] Executive Committee, “Sororities at Davidson College,” Letter to College President, December 1, 1997.