This week’s post is written by Dr. Anelise H. Shrout, a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Studies.

Over the past two semesters, I’ve had the privilege of trying out some new course ideas that blended digital humanities and archival work. The challenge of bringing #dh into archives and archives into #dh is that it can actually be quite a chore to translate historical data – as transcribed in minute books, maps, or letters – into a form that works for #dh visualizations and research. This year, I had two students whose projects used “analog” material from the Davidson Archives to create interesting and captivating digital artifacts, each of which showcased something new about Davidson history. These projects speak for themselves, but I thought I’d say a little about the process that each undertook to get from poring over manuscripts in the rare books room to these digital explorations of Davidson’s past.

Mapping Davidson’s Environmental History

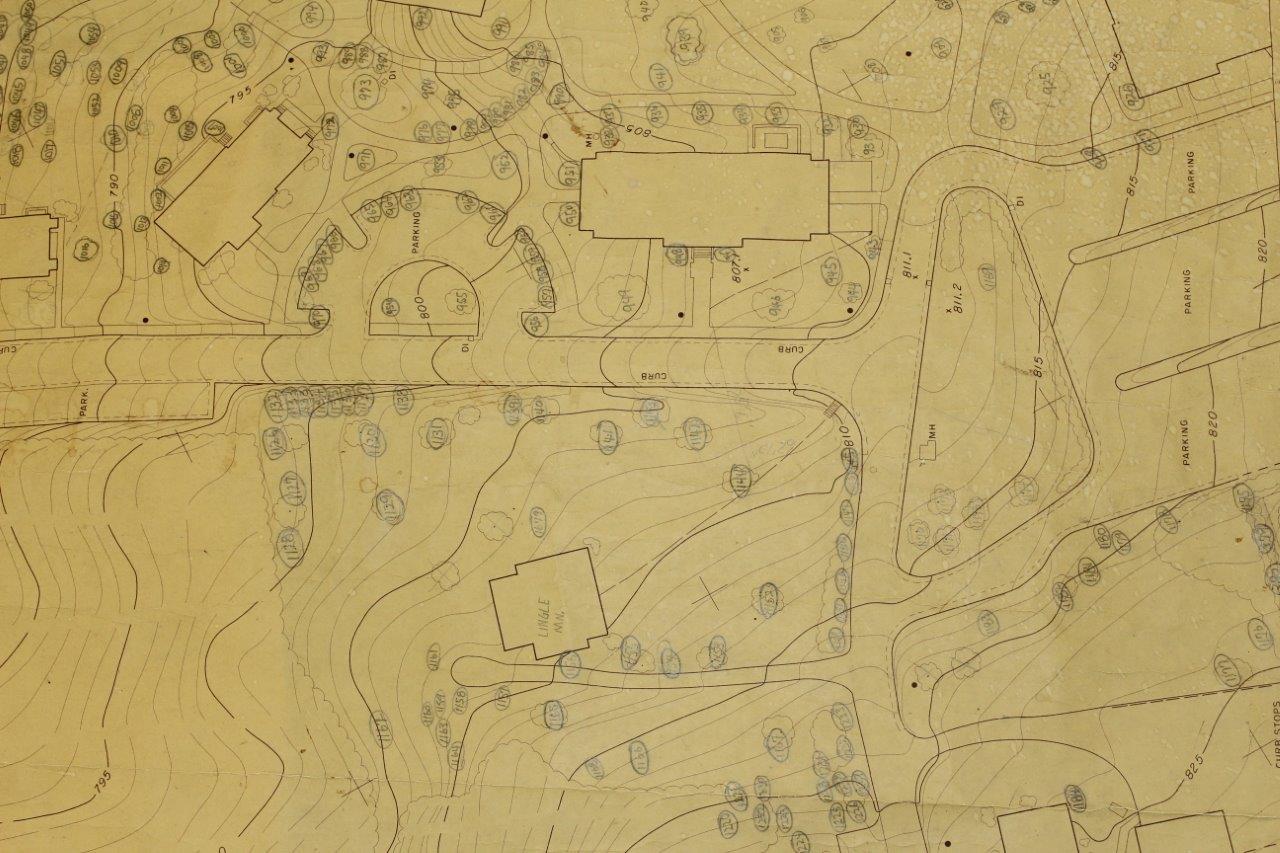

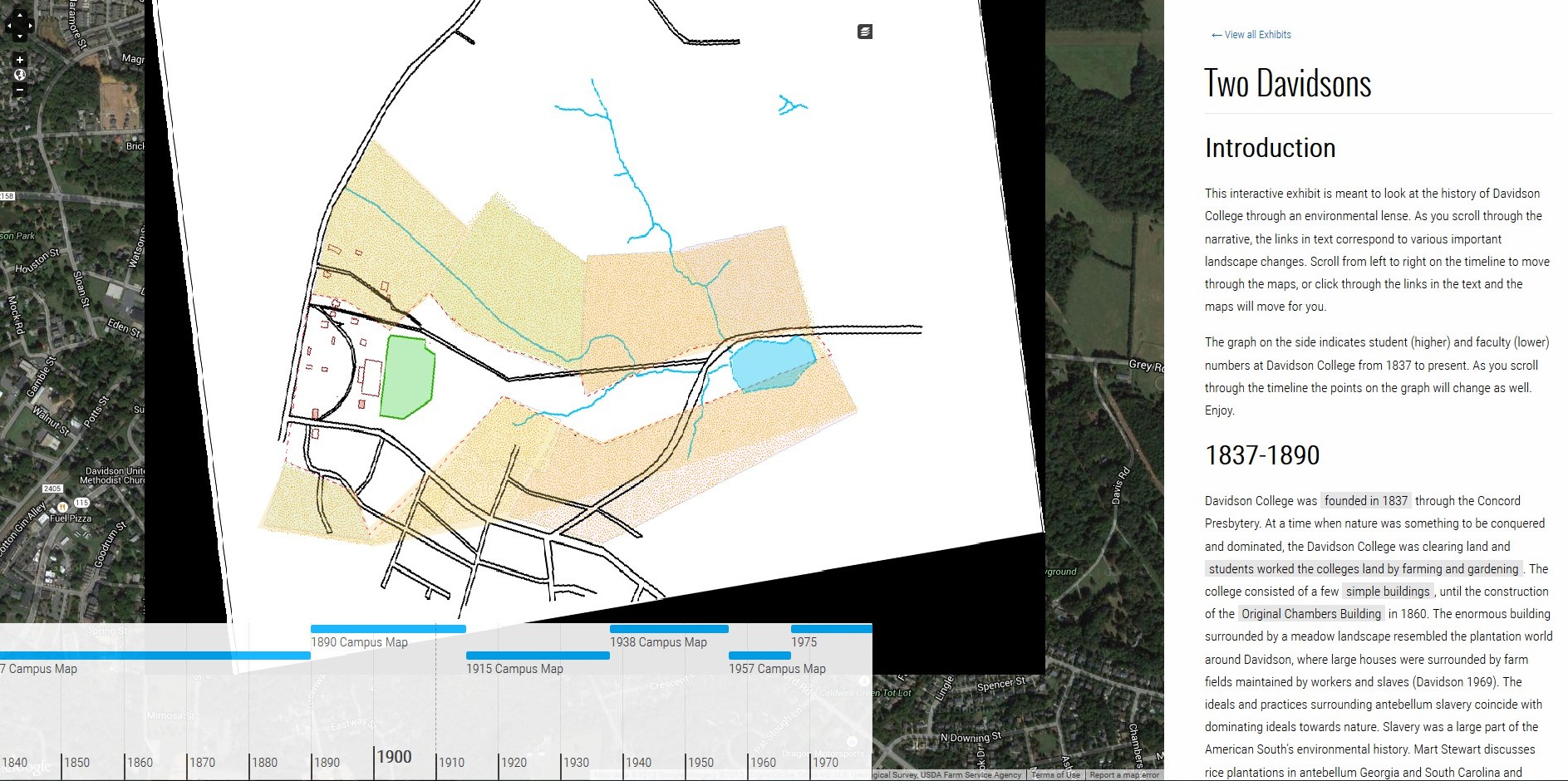

Sarah Roberts, a senior Environmental Studies major, undertook the impressive task of charting Davidson’s environmental development over time. Using maps like this one:

– and many more besides, she created a series of visualizations that documented different aspects of Davidson’s environmental history at different points in time. This was not an easy process. For each of the maps she used, she had to trace the outlines of important features (buildings, athletics fields, a briefly-present lake) and color code them according to their purpose.

She brought all of these together in an environmental studies capstone project, but also in a dynamic website which takes users through the spatial history of Davidson College and a bit of the town.

Mapping Davidson’s Institutional History

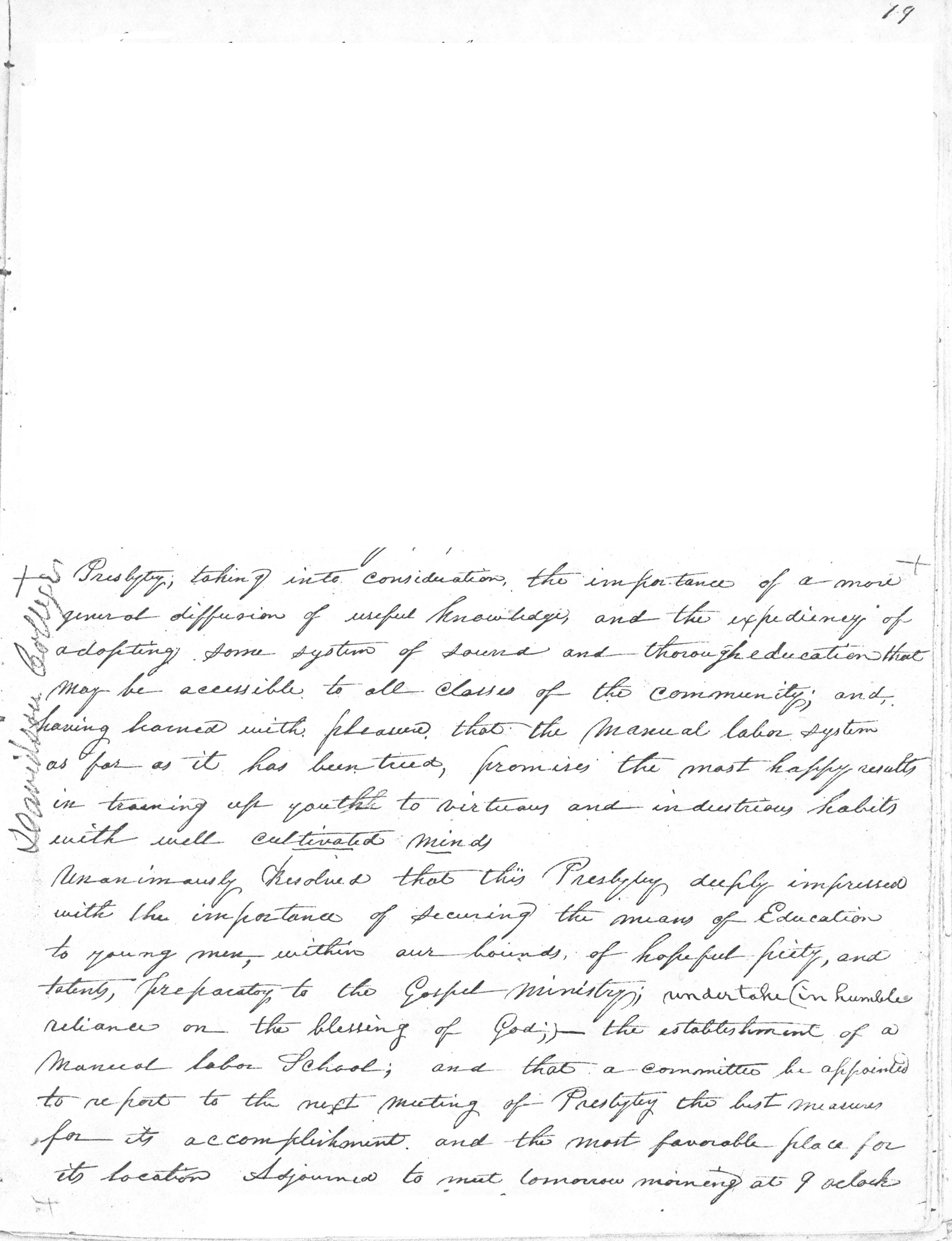

Avery Haller, a senior anthropology major also used the Davidson archives, but instead of tracking Davidson’s spatial history, she was interested in the college’s social and institutional history. Avery used the minutes of the Concord Presbytery, the Presbyterian group which was prompted by “the closing of Liberty Hall Academy (now Washington and Lee University) due to a massive fire” to found “a new place close to home to send their young men to school.”

Using documents like this one (which, happily, were transcribed):

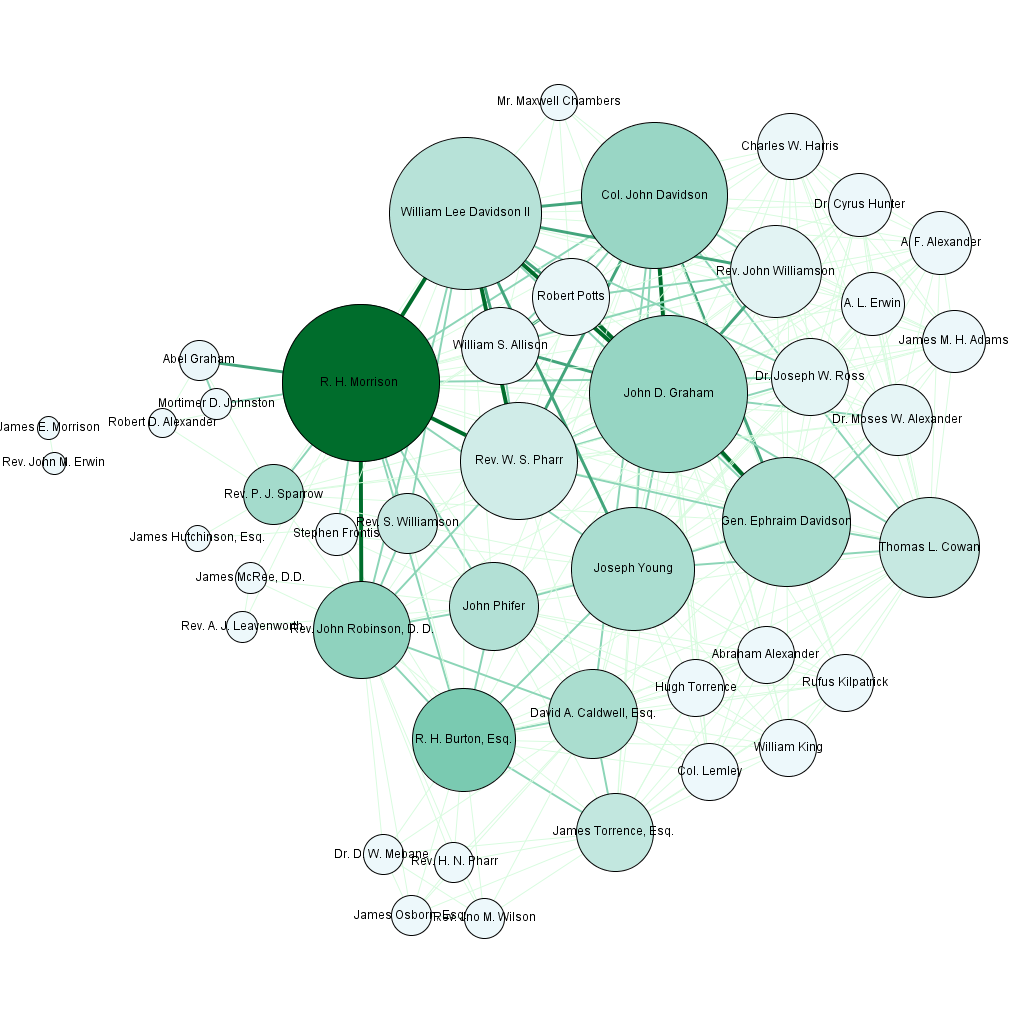

Avery was able to extract social networks – the ties that bound the various men (and they were all men) involved in Davidson’s founding together (She describes the technical part of this process here).

The finished network – the first Davidson College President, Robert Hall Morrison, is in darker green.

Ultimately, Avery concluded that both a close reading of the sources and a systematic analysis of connections among Davidson’s founders revealed “a picture of Davidson … that blend[ed] conservative values and an entrepreneurial spirit.”

Together, these projects point to the innovative work that can emerge when traditional historical materials are deployed in new ways. However, both of these projects took an extraordinary amount of time to accomplish – since before they could begin their analysis, both Avery and Sarah had to render historical “data” legible for digital tools. As one student noted in my class’s final presentations “As most of you have found, data entry is kind of tedious,” but I hope that these projects can help convince students and researchers alike that the intersection of #dh and archives can lead to some fruitful and interesting results.

Speak Your Mind