This is the first part of a two-part post by Carlina Green ‘20.

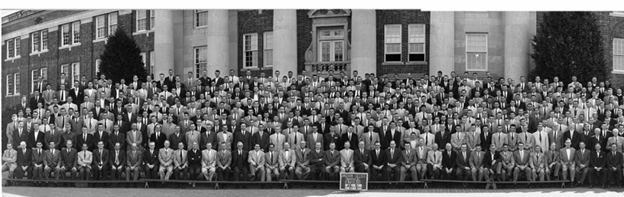

On March 8th 1955, around 900 members of the Davidson College community gathered in front of Chambers for a group picture. Yet, a notable population was missing; as archivist Jan Blodgett notes, “college staff are not included in the photograph.”

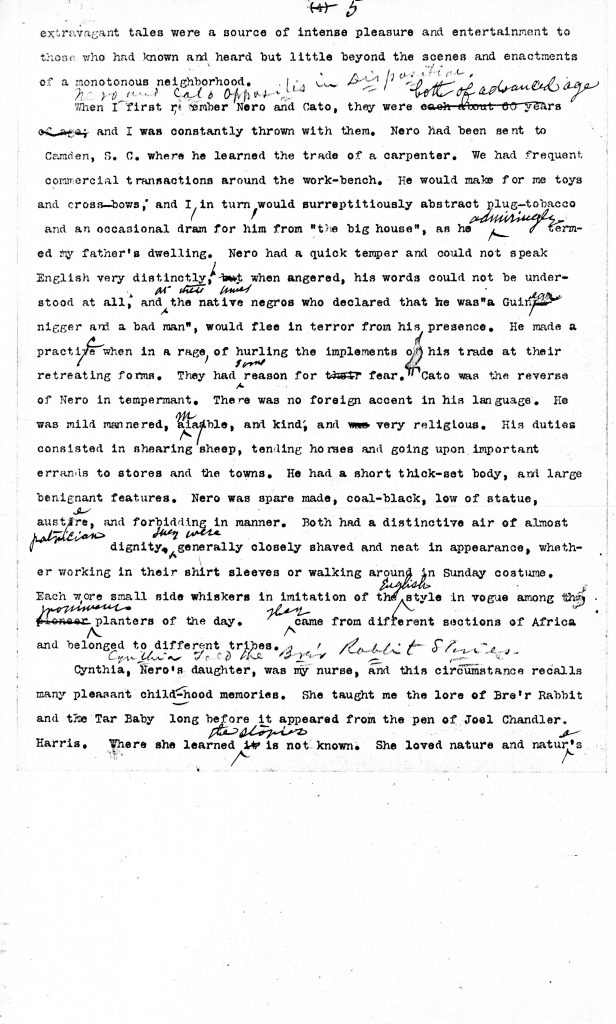

Their absence from the photo constitutes what Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot refers to as a historical silence. Trouillot theorizes:

Silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives), the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).[1]

Michel-Rolph Trouillot

In this instance, the historical silence occurred at the moment of fact creation, when the photo was taken. Silences involving staff frequently occur at the moment of fact creation, which means that they are underrepresented in portrayals of college life. A quick search of The Davidsonian reveals another example. While articles like this one discuss some staff members’ experiences as Davidson employees, very few document their life stories. Since 2016, only one “Staff Spotlight” has been published in the College newspaper—an interview with former Campus Police Chief Sigler. He is only one of over one hundred 21st century staff members whose stories should be recorded, from physical plant staff to dining services employees, from the counselors at Center for Student Health and Well-Being to the career advisors, from the registrars to the van drivers who take students to the airport. To what extent are their lives and experiences being documented in the sources that the College community creates?

My name is Carlina Green and I just graduated from Davidson while in quarantine, earning a B.A. in Latin American Studies with a history minor. While working at the Archives & Special Collections in my last semester, I had hoped to create sources documenting staff members’ lives and experiences by interviewing Vail Commons employees but was unable to do so because of COVID-19. A collection of their life stories would have been a valuable addition to the Archives, where, as JEC Project archivist Jessica Cottle stated, “we largely understand staff experiences through the lenses of their work life.” Because I was unable to create a collection of staff interviews myself during my time at Davidson, I am writing a call to action today.

[1] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, 20th anniversary edition,Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 2015, 26.