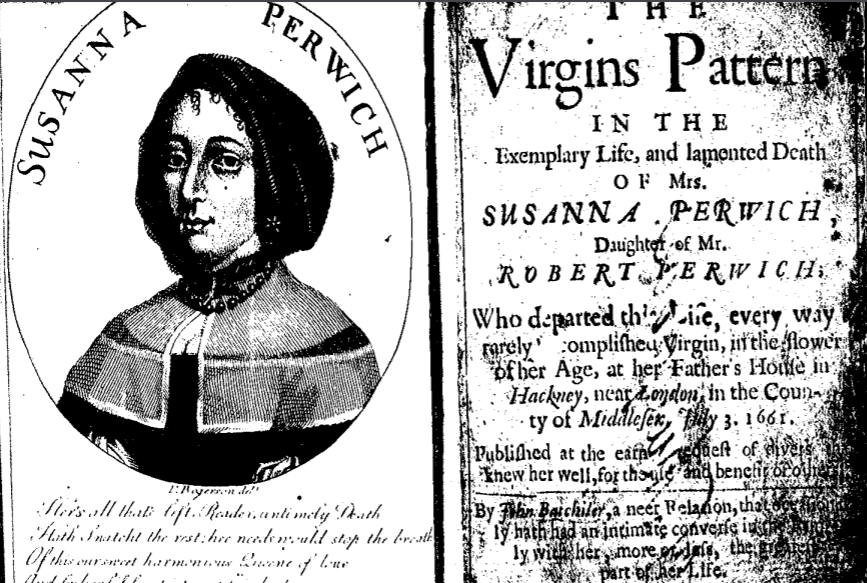

She in needles Art attain’d to be

Perfectly curious; every work

In which a cunning skill did lurk,

She had it at her fingers end,

And lov’d therein sit time to spend.

–John Batchiler, The Virgins Pattern, 1661

Though Batchiler’s verse is describing the excellent needlework of a Mrs. Susanna Perwich in 17th century London, fast forward nearly 400 years and I think most people would describe my own work as “perfectly curious”. Not my needlework (more on that later), but my work as a cataloger. I create records for the online catalog by describing library materials, assigning call numbers and subject headings, and attributing works to creators. All of that information creates connections to materials that help people find the things they are looking for.

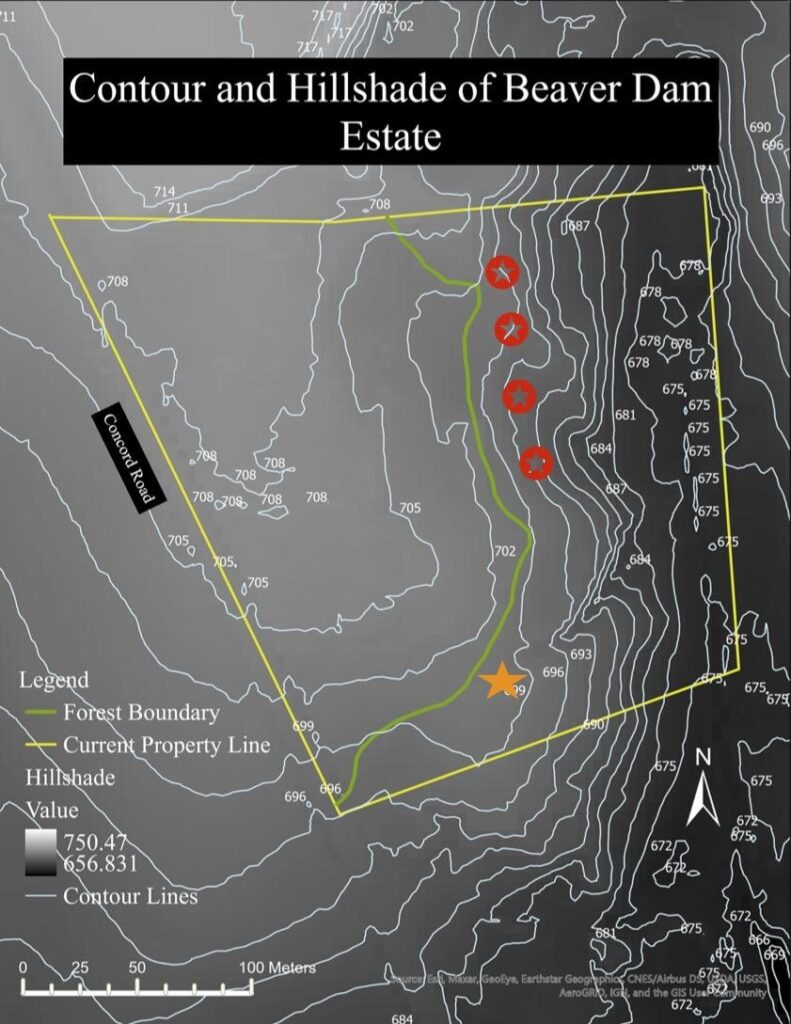

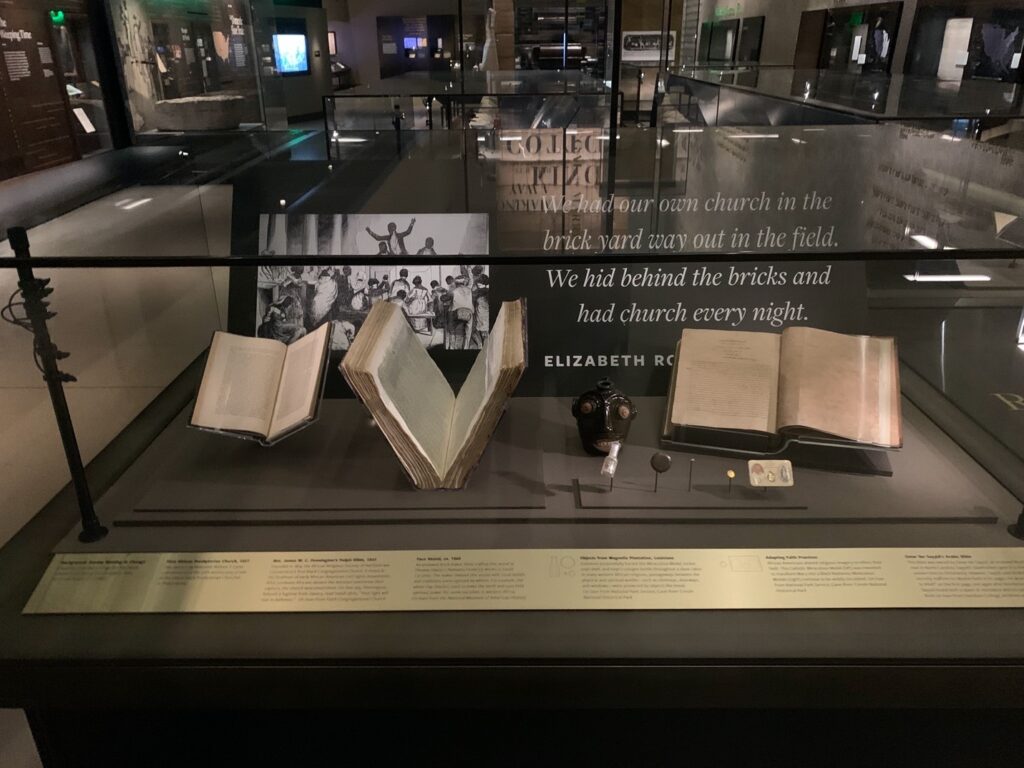

The perfectly curious work of cataloging has changed dramatically since the advent of online catalogs and increased accessibility to digital materials. Now, instead of working with physical books and paper card catalogs (remember those?), catalogers work with a variety of physical and digital materials and metadata schemas. So the title of ‘cataloger’ would be more accurately called metadata professional. And here at Davidson, I am not the only professional working with metadata. The bulk of the Davidson Library’s metadata creation happens in our Archives, Special Collections, and Community (ASCC) department. They have really spearheaded efforts to ethically and responsibly manage materials, starting with thinking critically about how collections are described.

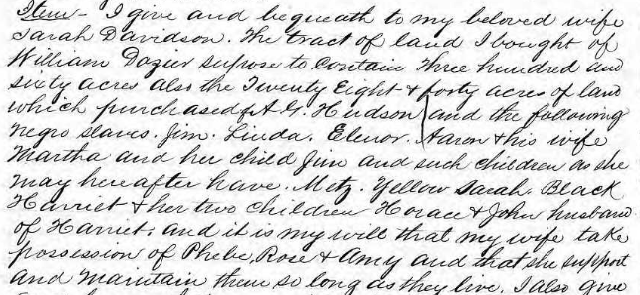

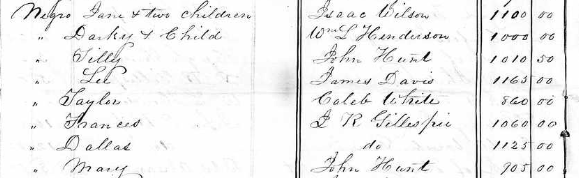

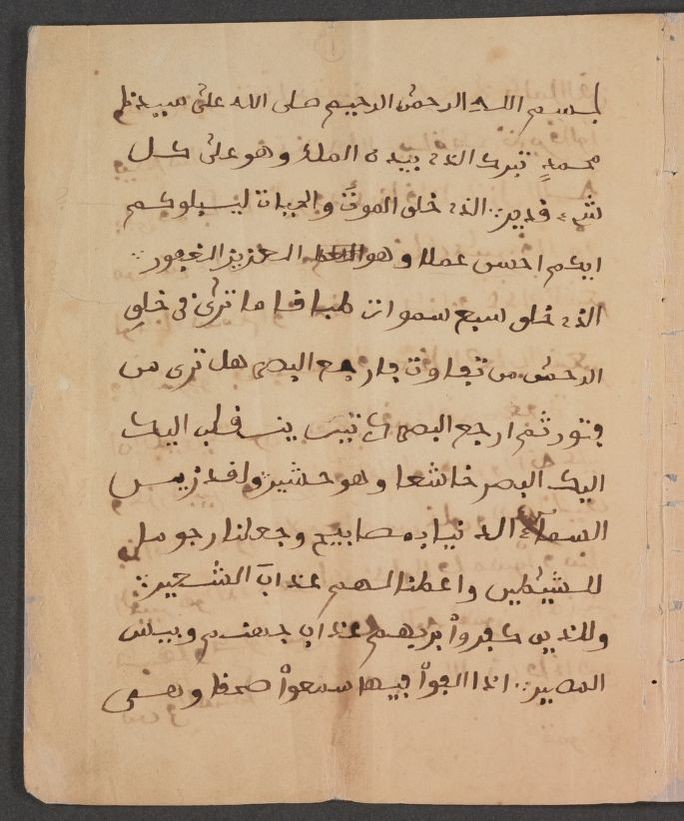

Why is metadata creation such a huge responsibility? Look at any record in any of our library systems such as Primo or ArchivesSpace. All of the access points such as names, places, dates, and all of the details that describe what a resource is or what it is about is metadata and that’s what we as metadata professionals are responsible for creating and maintaining. A decision is made every time a record is created, every time a subject heading is added, every time an item is given a certain call number. Those decisions can lead to more visibility and greater access to a resource, but they can also be harmful and completely erase materials or people from the catalog.

The librarians and archivists in ASCC and I are deep into the evaluation of our past metadata practices: what have we chosen to describe and why? How are we describing certain groups and what terms are we using? Can we make more connections between collections with a richer metadata description? Looking to the past is also helping us in how we are currently creating metadata for new collections. We’ve been working hard to show why metadata matters and who it impacts and make changes to ensure that materials are described and represented equitably.

This kind of work can be both physically and mentally intensive so it took me a minute to readjust focus when I saw a posting on a cataloging listserv that read:

Are you a metadata librarian or cataloger? Do you cross stitch and/or embroider? Or do you want to learn? I’m looking for you!

The post went on to describe a community project where metadata professionals would create a needlework piece that represented their unseen labor and how, without them, discovery just wouldn’t happen. How serendipitous! Other folks in other institutions were also working diligently in this area and wanting to express themselves creatively. I have no skills, ‘cunning’ or otherwise, in cross-stitch or embroidery, but I had to be a part of this project and leaped at the chance to interact with other community members, gain some outside perspectives, and learn a new skill.

Where else would I look for resources on how to cross-stitch or embroider but the library catalog? Metadata at work! I found some fantastic materials in the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library system and spent countless hours on YouTube learning about satin stitches, french knots, and aida cloth. For the project, each individual will create a needlework piece of their own design and it will be exhibited in the Spring of 2022. Though I am no Mrs. Susanna Perwich, I have also “lov’e therein sit time to spend” and can’t wait to see what the rest of the contributors have created. There will be a digital exhibit catalog (with plenty of good metadata to make it discoverable, I’m sure) so be on the lookout for my completed metadata embroidered piece next spring.