Jonathan Swann was a psychology major at Davidson, graduating in the class of 2019. At Davidson, he wrote for the Davidsonian, was a member of the Student Government Association, and was involved in College Democrats. Originally from Maryland, he currently lives in Central Florida working at a boarding school.

Each week during the month of March, Swann will offer a post analyzing different aspects of Davidson College’s hosting of the 1992-1994 Men’s Soccer Championship and the ways in which “Distinctly Davidson” impacted the event.

In this first part of the four-part series chronicling the untold story of the NCAA Men’s Soccer Championship at Davidson College, I’ll be focusing on the legacy of Davidson grad Charlie Slagle, who was the brainchild for the championship at Davidson. He passed away unexpectedly in July 2019 at the age of 67.[1]

Ironically, Charlie Slagle’s first sport was football, not soccer.[2] Slagle played one year of football at Davidson before switching to soccer and playing goalkeeper for the Wildcats.[3] After that, Slagle never left the soccer community.

At the time of his death, Slagle had been working for the Richmond Kickers, the United Soccer League team.[4] From Davidson to the Richmond Kickers, Slagle left an indelible mark on soccer in the United States.[5]

Five years after Slagle finished his playing career at Davidson, he returned to coach men’s soccer (in addition to baseball, golf, and women’s basketball!), leading the Wildcats to three Southern Conference titles and two conference tournament titles, including the remarkable 1992 underdog run to the NCAA Men’s Soccer Semifinals.[6]

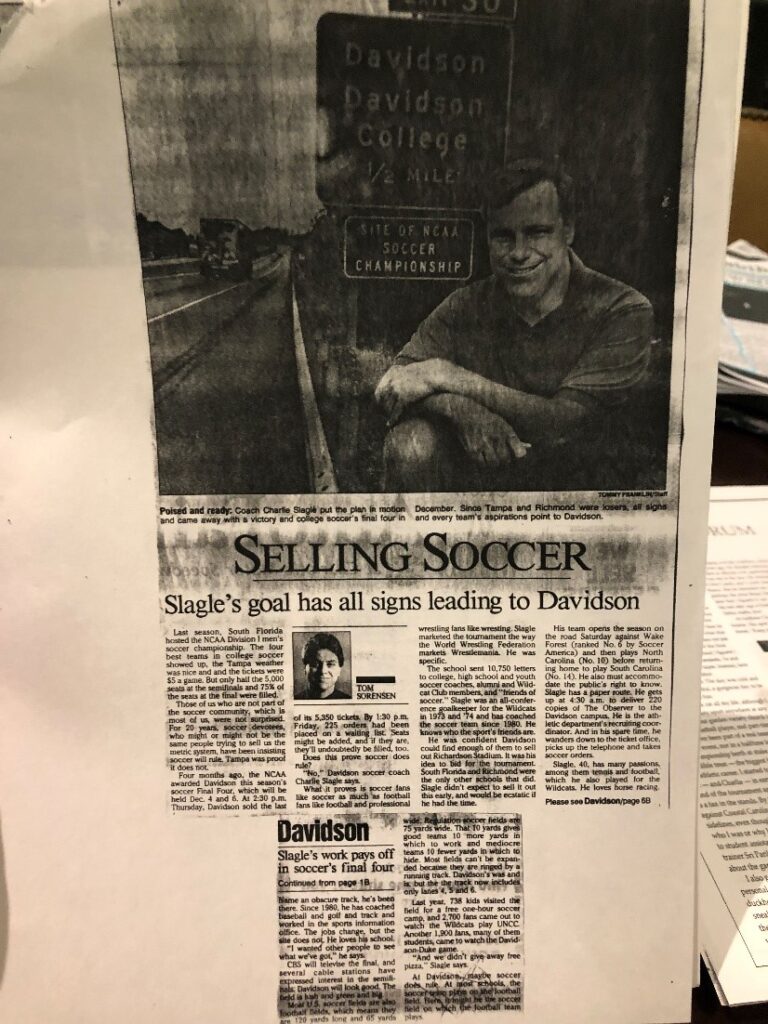

Slagle’s marketing prowess and relentless soccer evangelism proved highly consequential as he brought the NCAA Men’s Soccer Championship to Davidson and then to Cary, North Carolina, which remains the championship’s primary hosting site.[7] Slagle realized that with the right formula, the NCAA Men’s soccer championship could thrive.[8] That formula included strong community support, a more intimate stadium meant for soccer, and passionate administrative staff who were familiar with the NCAA and the logistics of hosting a championship.[9]

To me, Slagle epitomized how Davidson College graduates can develop disciplined and creative minds for lives of leadership and service.[10] Throughout his life and soccer career, Slagle fervently believed soccer could bring people together, led teams and organizations with empathy and devotion, and took on countless responsibilities to help events run smoothly.[11] I hope that these blog posts on the NCAA Men’s Soccer Championship and my soon-to-be published article will shine a light on the vision Slagle had for the NCAA Men’s Soccer Championship at Davidson.[12] Slagle told me when we chatted on the phone in April 2019 that he believed the underdog run in 1992 has outshone the unprecedented success of hosting.[13] The untold story of the hosting at Davidson should highlight one part of the remarkable legacy of Charlie Slagle.

Picture from the Davidson College website.

[1] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html.

[2] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html. Fox , John. “Fast Talking CV Grad Gets Kick at N.C School.” Press and Sun Bulletin. November 12, 1992.

[3] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html. Fox , John. “Fast Talking CV Grad Gets Kick at N.C School.” Press and Sun Bulletin. November 12, 1992.

[4] Scott, David. “A Force of Nature:’ Former Davidson College Men’s Soccer Coach Charlie Slagle Dies.” Charlotte Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.charlotteobserver.com/sports/college/article232225097.html.

[5] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html. Fox , John. “Fast Talking CV Grad Gets Kick at N.C School.” Press and Sun Bulletin. November 12, 1992.

[6] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019.

[7] Lynn Berling-Manuel. Phone interview with the author. July 2019. Trevor Gorman. Phone interview with the author. May 2019; Pat Millen. In-person interview with the author. November 2018. “DI Men’s Soccer Championship History” (NCAA, December 15, 2019), https://www.ncaa.com/history/soccer-men/d1.

[8] Charlie Slagle. Phone Interview with author. April 2019. Sorensen, Tom. “Selling Soccer-Slagle’s Goal Has All Signs Leading to Davidson.” Charlotte Observer, August 31, 1992.

[9] Peter Brewington, “Big Switch for Final Four: Amenities Gained, Atmosphere Lost at Ericsson,” USA Today, December 10, 1999; David Woods, “This Stage Is Just Too Large for College Soccer’s Top Act,” Indianapolis Star, December 13, 1999.; Jerry Lindquist, “Division 1 Soccer Tournament Leaves Sponsor Seeing Red,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 24, 1999; Alex Yannis, “Attendance Is Low for Division I Final,” The New York Times, December 14, 1999. [9] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html.

[10] Davidson College Statement of Purpose. https://www.davidson.edu/about/statement-purpose

[11] Giglio , Joe. “The Triangle Soccer Community Mourns the Passing of Charlie Slagle.” News and Observer , July 3, 2019. https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article232271397.html. Fox , John. “Fast Talking CV Grad Gets Kick at N.C School.” Press and Sun Bulletin. November 12, 1992.

Lynn Berling-Manuel. Phone interview with the author. July 2019.

[12] Pat Millen. In-person interview with the author. November 2018. Charlie Slagle, Phone Interview with the author, April 2019.

[13] Charlie Slagle. Interview with the author. July 2019.